The Mother of the Sea statue on the Nuuk seafront. Photo by amanderson2.

- Memories of a fading past

- The youth effect

- The Mother of the Sea speaks

- The new shaman

- Shamanism and the Church

- A tale of two statues

- The ‘comeback’

- Trump’s gambit

- Notes

Allaaritaa, like hundreds of people before him, migrated in 1901 from East Greenland to Friedrichsthal in the Cape Farewell region, the meeting-point between the thoroughly Christianised culture of the West Greenlanders and the more traditional shamanistic hunting culture of the East Greenlanders. He had travelled to Friedrichsthal to get baptised as a Christian, which he soon was, taking on the name Kristian Poulsen, but before that he was a shaman — known in Greenlandic as an angakkoq (plural angakkuit). The role of the angakkoq was multi-faceted, involving earthly functions like medicine, mediating in disputes, and enforcing moral norms, as well as spiritual functions as the link between humans and the spirit world. From his ‘helping spirits’, the angakkoq could obtain knowledge of proper behaviours and ensure bountiful hunts. Both men and women could be angakkuit.1

When Allaaritaa became Kristian Poulsen, the old shamanic religion was still widespread in the East; within a few generations, however, missionaries of the Danish Lutheran church had more or less wiped it out as an independent faith. Gradually, the wealth of knowledge that formed the oral codex of the angakkuit fell out of living memory — that is, until Greenlanders in the mid-to-late twentieth century started to revive it, seeking secure moorings and a unique Inuit identity from which to draw strength in the rushing squall of a globalised world. This is the story of how Greenlandic shamanism was brought back to life.

Memories of a fading past

Unlike many revivals, this one started sluggishly. Poulsen’s story as one of the last of the old angakkuit to migrate from the East became a point of curiosity to some West Greenlanders, serving as the basis for the 1952 novel Angakkoq Papik, but this book’s impact was limited due to the atmosphere of rapid modernisation then taking hold. Put simply, many people felt that shamanism was best left in history,2 and by this time the ‘original religion of the Greenlanders’ was largely being discussed in the past tense in the main population centres,3 at worst a relic of an uncivilised era and at best an oddity about which one might learn by speaking to elders.4 It was regarded by the Danish-speaking elite as a mostly vanquished foe. The question of whether the last ‘real’ angakkoq had passed away seemed to them of limited consequence, since their abilities were thought to be nothing but ‘second-rate magic tricks’ anyway.5 It is probably a testament to the sense of security surrounding the Christian regime that the Greenlandic postal service, under the administration of Danish governors, introduced stamps depicting the Mother of the Sea (one of the main spiritual figures in Inuit religion) and a scene from a shamanistic drum dance in the late 1950s and early 1960s.6

However, traces of the shamanic rituals, including use of the shaman’s drum (qilaat) and séances, survived in the East Greenlandic settlements around Angmagssalik/Tasiilaq until at least the mid-twentieth century, often existing alongside Christian church affiliation and surfacing mostly in private spaces.7 In 1957, the pastor in the town noted that ‘the East Greenlandic superstition … still plays a role for many in their world of imagination’. The bilingual Greenlandic/Danish newspaper Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten (A/G) reported that it was ‘still the case [in Tasiilaq] that the elderly take out the drum when they are at a party’, observing that it ‘goes without saying that all this cannot be wiped out … in the short time that has passed since colonisation began [in East Greenland]’.8 The people of Tasiilaq named one of their main community associations after the shamans,9 while even on the West coast the title of angakkoq was sometimes given to Inuit Christian figures — wise people who positively impacted their communities and performed some of the cultural functions of the shaman, like the polymath organist, poet, composer, and seminary teacher Jonathan Petersen.10

Few Christian Greenlanders had an active interest in returning to the old beliefs, yet there remained enough of an ambient curiosity about the spirits and the shamans in the 1960s for A/G to publish long-form pieces explaining Inuit folklore,11 and for the NAIP amateur theatre group in Nuuk, founded in 1959, to turn many of these legends into plays.12 The 1960s also saw efforts by the Danish Folklore Collection, with support from the Carlsberg Foundation (a science funding body associated with the brewery), to record and preserve drum songs (qilaatersorneq) from North and East Greenland, where they were still known. The Folklore Collection released four records of these songs ‘so that every Greenlandic family, adults and children, can have the opportunity to listen’. Interestingly, the A/G article reporting on this project made a passing comment that prefigured the more thorough reclamation of Inuit spiritual traditions that lay in future, playfully suggesting that the UN could adopt the Inuit practice of drum battles to resolve disputes ‘without weapons and bloodshed’ in its mission to maintain peace between nations.13 That the old ways contained truth and wisdom not native to the new regime would be an increasingly popular belief as the decades passed.

The youth effect

The 1970s were marked by worldwide cultural and political upheavals that brought many of the foundational blocks of the Western hegemonic structure into question, key among them being Christianity, reserved social morality, and the patriarchal structure of family and society. The rock and roll musical revolution continued apace, as did climate activism and the burgeoning indigenous movements that sought greater civil rights and protections for indigenous cultures in colonised nations. Meanwhile, New Age spiritual philosophies often looked to indigenous religious practices — or caricatured versions of them — for inspiration, seeking new yet old ways to feel connected with the earth and the supernatural. The women’s liberation movement also found its stride and called for a fundamental restructuring of gender norms so as to release women from the bonds of their traditional functions in the family and home. Much of the social energy behind these phenomena was centred in the major cosmopolitan cities: places where large numbers of young people, many of them university students, could meet, talk, and organise.

Greenland may have lacked some of these underlying circumstances, having a population equivalent to a small European town and no university to speak of (until the University of Greenland, or Ilisimatusarfik, was founded in 1987), but it did have the cultural infrastructure to foster home-grown talents, including a radio station, newspapers and magazines, cultural and arts associations, and, not least, close ties with Denmark, where many Greenlanders went to study or work. It also experienced many of the social conditions that made political activism and cultural rebellion feel necessary.

Women, who in the days before colonisation had an independent and often powerful role in processing game (i.e., extracting meat and materials from hunted animals), distributing resources, and maintaining hunting equipment and boats, found themselves relegated to a subordinate position as they underwent a process of ‘housewifisation’. Whereas once they could be community leaders and even angakkuit,14 women were now frozen out of political participation and could not sit on the local councils introduced in the 1880s or the district councils introduced in the 1920s, only gaining the right to vote in 1948, more than thirty years after women’s suffrage in Denmark.15 Contraceptives and birth control were welcomed by most in the women’s liberation movement because they offered women a higher degree of sexual freedom, but in Greenland a Danish ‘family planning’ programme launched in 1967, later known as the ‘Spiral Case’, installed intrauterine devices (IUDs, or ‘coils’) in thousands of Inuit Greenlandic women, in many cases without their knowledge or consent, robbing them of their reproductive autonomy.16 All the while, old systems of communal cooperation and ownership were being replaced by Western-style ‘jobs’, home ownership, credit (and therefore monetary debt), and individualised personal responsibility, bringing Greenland closer to the conditions of a Western capitalist economy.17

Some of Greenland’s key social movements emerged from the need to adapt and respond to these changes. The Greenland Women’s Association, or Arnat peqatigiit Kattuffiat, (APK), was founded in 1948 with a mission to facilitate ‘mutual aid and qualification in domestic matters’, but in time it became more political as the exploitation of women’s labour emerged as a substantive point for political discussion throughout the 1950s and 1960s, and as the ‘proletarisation’ of Greenland’s workforce led to social dislocation, poverty, and an increasing reliance on sex work to supplement meagre incomes. Young Greenlanders who had studied in Denmark brought home the politics of women’s liberation, and in 1975 the Kilut movement was founded, representing a more ‘radical’ feminist vision of the future in which women are freed entirely from the false restrictions of the gendered power hierarchy, although the exclusion of women from the Danish-Greenlandic Home Rule Commission tasked with exploring the feasibility of self-government in Greenland signalled a continued second-class status.18

While Greenlandic women grappled with the generational loss of power, some pockets of Greenlandic society, particularly those involved in youth movements, were also grappling with the denigration of Inuit culture in favour of Danish ‘modernity’, and exploring ways to recover lost traditions. Starting in 1976, the Aasivik festivals (named after the aasiviit summer encampments where Inuit Greenlandic communities came together to trade and converse) were annual events held every summer up to 1996, featuring music and entertainment as well as political discussion.19 The Aasiviit unapologetically celebrated Inuit culture, encouraging young people to take up kayaking and other traditional skills that had fallen away, with the opening ceremony of the 1977 iteration, held in Qullissat on Disko Island, featuring drum dance performances by three East Greenlanders: Milíkka Kûitse, Gudrun Erdakm and Tobias Tukula. One of the organisers of the 1977 festival, Aqqaluk Lynge, lamented that ‘many Greenlanders were no longer interested in their own culture and traditions’ at the time; Aasivik was a way to give those traditions new vitality.20

The youthful energy of the Inuit cultural revival was given popular expression by the use of qilaat drums in songs by the Greenlandic rock band Sume in the 1970s,21 and towards the end of the decade, group trips by school educators and the Tuukkaq Theatre (a Greenlandic theatre group in Jutland, Denmark) to Inuit communities in Canada and Alaska provided opportunities to learn their drum dances and deepen pan-Inuit cultural ties, leading to children’s productions on Greenland Radio based on stories from the time of the shamans.22 These developments did not pass without controversy, however. Karsten Sommer, who worked with the record company Ulo to release recordings of East Greenlandic drum songs in 1977, later recalled the reaction of an unnamed high-ranking politician: ‘You have to stop doing that. It has to be forgotten. It’s dead.’23

The Mother of the Sea speaks

Pan-Inuit cultural exchanges and new artistic expressions continued to cement a more prominent role for Inuit traditions in Greenlandic society into the 1980s and 1990s.24 Founded in 1984, the Silamiut theatre group specialises in productions taking inspiration from Inuit mythology, often incorporating qilaat, mask dances, and shaman characters, with an operational focus on public engagement with schools and community groups.25

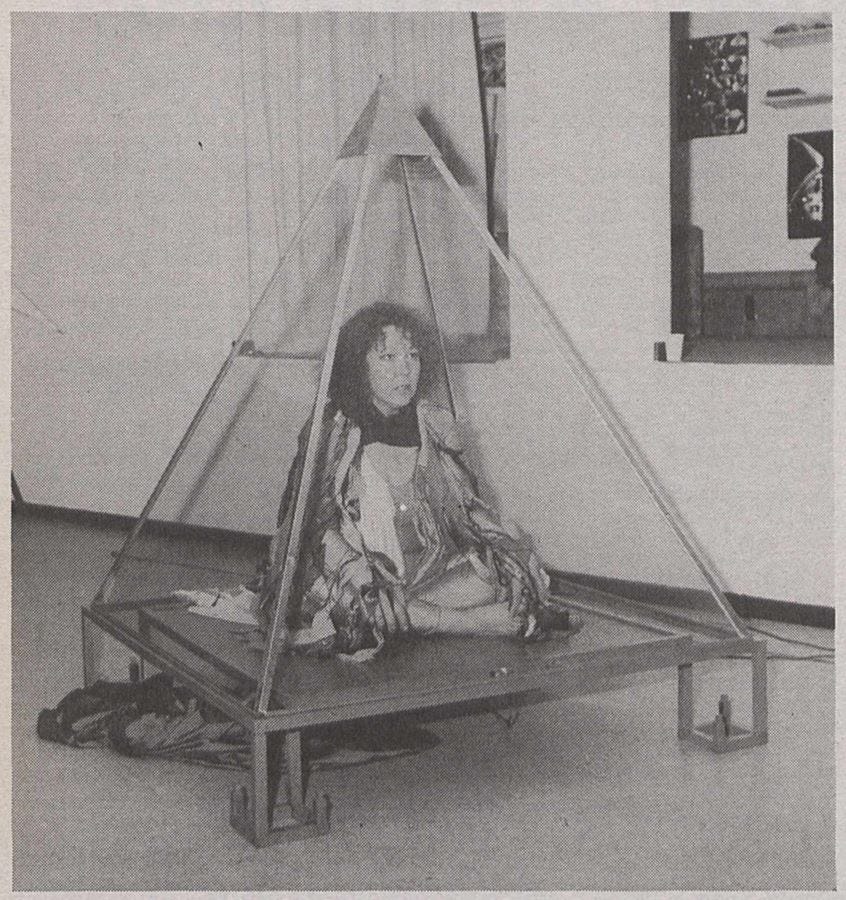

One of Silamiut’s productions, Aarit (Stop en Halv in Danish), which debuted in front of an audience of ‘several hundred’ at Nuussuaq Hall in Nuuk in 1989, follows an old angakkoq on a vision-journey around the modern world. After performing a drum dance, he approaches the Mother of the Sea, Sassuma Arnaa, who sits cross-legged within a glass pyramid, to ask if she would accompany him on his final expedition. She cannot, but she tells him to set off anyway. What the angakkoq sees troubles him deeply: terrified multitudes fleeing from war and bombs; widespread unrest; an imperious military general who bosses around the exhausted masses; and, in the final act, astronauts who are sent to patch up an ozone layer perforated by the emissions of humanity. Several times the angakkoq asks the Mother of the Sea to be relieved from his burdensome expedition, but each time she tells him to continue. The message of the play, if it was not already clear, is driven home by Sassuma Arnaa’s closing speech to the weary angakkoq: ‘You can decide for yourself what the world will look like. If you could have seen the world seven generations ahead, you wouldn’t have treated the world like this.’26

Aarit perfectly captures the intermixture of traditional Inuit iconography and modern humanitarian and ecological concerns that powered the youth movements of the day. It brings together past, present, and future, and posits that true wisdom lies in the fusion of all three, entailing a greater cognisance of the fact that we are part of a continuum; that just as the actions of our ancestors shape our reality, so too will our actions shape the realities of those not yet born. That it is the feminine figure of Sassuma Arnaa and not Yahweh or another traditionally masculine Christian figure who imparts this wisdom on the angakkoq is significant in multiple ways. Christianity is Greenland’s present, but that present is stained by numerous interminable perils, many of them rooted in global problems that feel beyond the tiny nation’s control — the threat of war, the erosion of the earth’s natural atmospheric shields, and the endless drive to exploit natural resources for profit. Aarit is not about faith per se, but it certainly touches on the lost wisdom of Greenland’s pre-Christian past, and while it does not depict the social order of the angakkoq as an ecological utopia — after all, it is him and his society that receive the Mother of the Sea’s scalding lesson — it leverages the theme of a once-and-no-more sense of connectedness with the natural world, spirits and all. The adoption of Sassuma Arnaa as the mouthpiece of wisdom also serves to elevate the voice of the Greenlandic woman far above the station of the passive housewife.

Beyond theatre groups, the quest to revitalise Greenlandic drum dancing was often carried forth by passionate individuals with no organisational backing. Often these were individuals with a direct personal or family connection with the tradition, for instance through a parent, grandparent, or childhood neighbour who knew drum songs, but sometimes they had simply witnessed drum dancers in adulthood — at arts festivals, for example — and been inspired to take up the drum themselves. In a sense, the revival had come at the last possible moment, as the final generation of Greenlanders who clearly remembered a time when drum dancing was part of the everyday ordinary was by now dying off, taking with it the living knowledge of drum dancing as a historically contiguous phenomenon spanning back to the pre-colonial age.27 A single additional generation of ambivalence could very well have seen its effective extinction.

One campaigner who made an impact was Pauline Motzfeldt Lumholdt, a West Greenlander who first saw drum dancers performing in Thule, in the North, between 1979 and 1982, and learned from them ‘the mystery and rhythm of the drum dance’. In 1985 she collaborated with KNR-TV to broadcast performances by the region’s dancers, and in the early 1990s she began writing educational textbooks on the subject to preserve the knowledge. She told A/G that she was ‘annoyed that West Greenlanders are far too reluctant when it comes to preserving drum dancing’, declaring that ‘this form of dance is something we have inherited from our ancestors that must be protected before it becomes extinct’.28 Lumholdt’s sentiments regarding the value of Greenlandic culture — that it is a unique cultural resource and an invaluable source of pride and identity — were by the 1990s fairly mainstream. The artist Jessie Kleemann, who based some of her work on Inuit religion and shamanic rites, argued in an interview with A/G in January 1992: ‘Our cultural heritage is our strength.’29

An A/G editorial later that year suggested that this renewed interest was a natural response to the cultural dislocation created by rapid Westernisation: ‘Greenland has struggled with its cultural identity for several decades. The pressure of development on Greenlandic society created rootlessness, and quite naturally there was both a cultural and political reaction.’30 In 1997, another Greenlandic artist, Dorit Olsen, proclaimed; ‘When you know the Greenlandic legends, you know more about Greenlanders.’31 These comments all point to a conception of Greenland’s ancient cultural roots as the spiritual wellspring of the Greenlanders, so that even if a Greenlander knows little about them, the legends contain something of the essence of the national character, and as such they have innate value that transcends their connection with ways of life that are in most ways now defunct. There is arguably no greater expression of this re-normalisation of Inuit Greenlandic culture than the Katuaq Cultural Centre in Nuuk — one of the most visually striking structures in all Greenland, it derives its name from the stick used in drum dancing, and its opening ceremony in 1997 featured a drum performance.32

In spite of all this fresh activity, the spiritual beliefs that gave precolonial culture much of its meaning were still remarkably absent from the revival movement by the close of the twentieth century. The researcher Merete Demant Jakobsen, who first became interested in Inuit religion after seeing a Tuukkaq Theatre performance in Jutland in 1980 and studied the subject in depth, concluded in 1999: ‘As far as I have been able to establish … traditional shamanism has not been revived in Greenland.’33 That was about to change.

The new shaman

The twenty-first century has seen efforts at effectuating a revival of the spiritual as well as cultural aspects of shamanism, catalysed by a rising national self-confidence, a desire to reconnect with nature and Greenlandic heritage, and a yearning for powerful anti-colonial symbols in an age of cultural dislocation and uncertainty. The movement has so far been characterised by ‘a low degree of institutionalisation and organisation’, consisting mostly of personal stories loosely woven together,34 but there were certainly institutional catalysts, perhaps chief among them being the educational reforms implemented since the 1950s.

Religious education up to then had been dominated by biblical fundamentalism, as stories like that of Adam and Eve were presented literally, while other subjects like art and history were also heavily influenced by Lutheran sensibilities, but from the 1950s education was transformed by the arrival of many Danish teachers who were sceptical of biblical fundamentalism. Religious studies were injected with a more critical perspective, and other subjects were ‘de-Christianised’. The School Act of 2002 changed things still further, reforming religious education under the banner ‘religion and philosophy’ and introducing other faiths to the curriculum, including Inuit religion. Ministerial guidance instructed teachers that ‘it is expected that students can assess and apply the Inuit religion and culture as an element of personal identity, self-esteem and spiritual growth’.35 Greenlandic children are now guaranteed to learn about the beliefs and rituals of traditional Inuit cosmology and to encounter it on an equal footing with Christianity.

Many children will also get at least one chance to learn about drum dancing in a practical setting when drum dancers are invited to lead workshops in schools, instilling a sense of ownership over the tradition.36 One student from Sisimiut who attended a workshop in 2013 said: ‘I think it is time for young people to learn more about our cultural heritage. We should not be ashamed of the drum song, but on the contrary, start to be proud of it.’37 After a two-week qilaat teaching series for the third-graders of Nuuk in the autumn of 2022, head of the Nuuk Music School Pipaluk Lynge Berthelsen said that children should know about the drums both because of their historical significance and because of their relevance in the present, calling for a cultural change to ‘normalise the use of Qilaat in modern-day Greenland’.38 Children’s books based on Inuit legends also promote knowledge of the old ways in the younger generations.39

Various steps were taken in the late 2000s and 2010s to channel the revival movement into specific institutions where it could be nurtured and expanded, and over time this has also catalysed the emergence of a more spirituality-oriented movement. In 2010, this led to the foundation of the Inngertartuti drum dancing association in Nuuk,40 followed in 2014 by a conference in the Katuaq arts centre which gathered together many of the country’s leading drum dancers and invited members of the public to learn and participate,41 and then by the formation of another group, Nuummi Peqatigiiffik Inngertartut, later that year.42

Such was the sense of confidence and pride surrounding the revival movement that some organisations began the task of exporting it to the rest of the world. In November 2014, the Slovak Spectator reported that the town of Zvolen in central Slovakia had a few weeks prior ‘welcomed Angaangaq Angakkorsuaq, a shaman, from the Kalaallit nation in Western Greenland’, who gave a guest lecture at Zvolen’s Technical University and spent time speaking about spiritual matters with a microphone in the town centre.43 Angaangaq, who now lives in Austria and says he has visited over 70 countries in his capacity as a travelling teacher and speaker, is part of a new wave of Inuit spiritual revivalism that emerged in the twenty-first century, one that centres on belief rather than just practice. He runs a network of Greenlandic Elders called IceWisdom, and describes himself as ‘a shaman, traditional healer, storyteller and carrier of the Qilaut (winddrum), whose family belongs to the traditional healers of the Far North’.44

Angaangaq’s story is rooted in the suppression of shamanism under the Lutheran regime and the subterranean transmission of traditions from generation to generation that it necessitated. A profile of Angaangaq by the Italian National Association of Ecobiophysiology narrates his early life, saying that by the time of his childhood in the 1960s it had been ‘200 years since a shaman had been trained in his country’, but his grandmother believed that he had ‘it’ — the spiritual gifts or wisdom necessary to be an angakkoq. In 1963, two young men from his community noticed a trickle of water on a nearby icecap during the dead of winter, and in the following years the trickle became a gushing stream as the ice cap depleted. Then, in the early 1970s, Angaangaq ‘received from the Elders of his people the task of bringing the message to the world that the ice was melting’, according to his telling. His mission, ironically, was to ‘melt the ice in men’s hearts’ so that they could see they error of their ways, though he only started to commit himself wholly to the task in 2004, when he ‘became a shaman working directly with people in order to contribute to a spiritual change’, opening a spiritual healing clinic near Kangerlussuaq.45

IceWisdom, which grew out of that endeavour, is an international organisation that specialises in seminars, spiritual healing, and faith-based activism. Its raison d’être is the climate crisis — with Greenland being ‘Ground Zero’ for the catastrophic effects of global heating, IceWisdom calls upon ‘the ancient wisdom of the tradition of the Far North’ to urgently restore ‘harmony in our lives’ and balance with nature,46 because, as Angaangaq puts it, ‘we need our Mother Earth’.47 Delivering this message has created opportunities for Angaangaq to meet two popes, the Dalai Lama, and secular leaders like Nelson Mandela, and to serve as a representative of the Arctic peoples at the UN General Assembly.48

Angaangaq and IceWisdom are fascinating for many reasons. In bringing Inuit legends and rituals to the rest of the world — evangelising, in a sense — IceWisdom is effectively reversing Greenland’s perennial role as a religious importer rather than exporter, belatedly fulfilling the suggestion made by an angakkoq in the early stages of colonisation that a shaman be sent to Europe to teach these people how to behave.49 Yet, while at least superficially grounded in Inuit religion, the ideas that Angaangaq preaches, often expressed in terms of Mother Earth, Gaia, inner peace, balance, and other non-specific concepts, are in some ways closer to universalist pantheism or New Age spiritualism than traditional shamanism, as has been noted by researcher Sidse Birk Johannsen.

In a paper exploring the ‘revitalisation’ of Inuit shamanism in Greenland, Johannsen distinguishes between two very different phenomena. On the one hand, mainstream and New Age revitalisation trends are syncretic, fusing traditional beliefs with modern ideals like wellness, oneness with nature, human unity, and self-actualisation, and making participation in the traditions open to all regardless of ethnicity, location, or faith, as seen for instance in Greenlandic skin care and clothing brands that draw inspiration from the Inuit past. On the other hand, those trying to revive shamanism as an ‘ethno-particular niche religion’ view it as belonging wholly and exclusively to the Inuit people and reject ‘what they believe are Western-influenced interpretations and adaptations’. They do not wish to see its appropriation by others as this would dilute their own unique heritage.50 As an example, one of the traditional arts that colonisation quashed, tunniit — skin art formed of a series of dots on the face — was reintroduced to Greenland in 2017 with the help of Inuit artists from Alaska, and many of the Greenlandic women who opt to get them do so ‘for very personal reasons and out of [their] human and spiritual values as indigenous people’, meaning their resonance often cannot easily be explained to non-Inuit people.51 The emerging culture around these tattoos is exclusive in that they are not meant for general adoption.

Johannsen also notes that revitalisation movements are strongest among Greenlanders living in Denmark and the heavily globalised West Greenland, where ‘contact with the global community and especially the former colonial power, Denmark, is most pronounced’. Inuit in these places might feel ‘a greater need to express their ethnic affiliation explicitly by participating in revitalisation’, such that in some instances the people who are most passionate about the ethno-particularity of Inuit traditions are the very ones with the weakest familial or personal connections to said traditions; in other words, they are people seeking to reconnect with an identity from which they had been alienated by globalisation.52 These individuals are often attracted more to the symbology of the traditions than to the beliefs they represent. As Johannsen points out, there is ‘a big difference between interest in and use of original religious motifs and then a definite practice of traditions and beliefs from Inuit religion as a resumption or continuation of the old tradition’.53

Syncretic tendencies involving both New Age religious ideas and Christianity seem to be widespread among those who practice shamanism or its associated traditions in modern Greenland. The strength of Christian identity in the country plays a role here, as some practitioners feel the need to hold onto the teachings of the church and return to the animism of their ancestors, sometimes because they want to lend legitimacy to the latter by attaching it to a widely-accepted belief system, and sometimes because they subscribe to a universalist view of religious truth in which all spiritualities are equally valid. This is not always the case — some drum dancers, for example, stress that they only sing songs that do not have direct links to ‘paganism’ because of their Christian faith54 — but the integration of belief systems is a recurring theme in the personal testimonies of the revival participants, especially the testimonies of leaders in the movement.

Well-known spiritual healer and clairvoyant Maannguaq Berthelsen, who was at the height of her popularity in the 2000s when she was interviewed by Danish documentarians, claimed to have received her calling in visitations both from the Lord of Power and Mother of the Sea from Inuit cosmology and from the prophets Abraham and Moses from the Old Testament. She initially drew authority from this dual sanction, even if later in life she turned against Christianity, believing that it had robbed Greenlanders of their ‘spiritual identity’.55 Another popular spirit medium active in the 2000s, Jukku Hansen, became a faithful Christian as a young man and held onto his belief in the words of the Bible even as he took up shamanism, explaining to interviewers that every soul he interacts with through his work ‘belongs to God’.56 Hvishu, also known as Robert Peary, was a prominent figure at the 2014 drum dancing conference in Nuuk, and, though not personally a Christian, he worked with the theologian Magnus Larsen on a book exploring the similarities and synergies between the two faiths in which Larsen argued that Hvishu’s spiritual ideas could be ‘a support for truly Christian living’.57

Finally, Leif S. Immanuelsen, one of the most famous drum dancers in Greenland, sees qilaat as ‘a sacred instrument’ and uses drums to enter trances, summon his helping spirits, and contact the dead. He began drum singing in 2002 and subsequently made it his mission to ‘change Christian religious ceremonial practice’ to include the drum. Despite his emotional investment in making the church a more representative institution, he is personally very sceptical of Christian doctrine, telling the researcher Juaaka Lyberth: ‘I believe more in myself than in the Christian God.’58 There are many others who draw from both Christian and ancient Inuit beliefs and practices, combining them in whatever manner makes the most personal sense and often adding in universalist and New Age sentiments, such as the belief that ‘we are all gods’.59 Belief in ghosts is also very common among Christian Greenlanders, which some researchers believe is a holdover from the shamanic past.60

Shamanism and the Church

The attitude of the Lutheran church towards the Inuit religious revival is complex, sometimes amicable and other times outright hostile, depending on the context and the nature of the interaction. In 2002, when shamanic practitioner Maannguaq Berthelsen was invited by a high-ranking civil servant to conduct a healing and exorcism ritual at the new Home Rule administration building in Nuuk, Bishop Sofie Petersen, head of the Church of Greenland, was furious, calling it a mockery of ‘our entire Christian tradition’.61 This scandal resulted in the firing of the civil servant and the collapse of the coalition arrangement between the Inuit Ataqatigiit and Siumut parties, as some complained that it made Greenland look backwards.62 In 2015, Lutheran priest and theologian Minna Winsløv went so far as to call shamanistic claims of intervening with the souls of the dead ‘megalomania — an incredible self-exaggeration and making oneself God’.63

And yet, in September 2012, Petersen and Mimi Karlsen, the Culture, Education, Research and Church Affairs, invited drum dancer Leif Immanuelsen to perform at that year’s conference of priests in Sisimiut. It was not intended as an endorsement of further integration but rather a ‘meeting between Christianity and the original Inuit culture’, but it was nonetheless expected by Immanuelsen to start a conversation about how the drum might be incorporated into church services in the future.64

Some form of fusion between Christianity and Inuit spiritual traditions is increasingly viewed in wider Greenlandic society with a sense of inevitability.65 It is also seen as virtuous. At the ceremony announcing that Immanuelsen would be Sermersooq Municipality’s cultural ambassador in 2016, mayor Asii Chemnitz Narup said that ‘the idea of weaving cultures and perhaps even religions together is very beautiful’.66 Growing national and international recognition of Inuit drum dancing as a defining aspect of Arctic cultural heritage has only increased the pressure on the church. In 2008, when drum dancer Anna Kûitse Thastum was awarded the national Culture Prize, Tommy Marø of the Ministry of Culture described drum dancing as ‘one of the most important elements that we have inherited from our ancestors’.67 The Greenland postal service unveiled two stamps based on drum dancing in 2013,68 and when Maniitsoq Museum organised an event on Greenlandic cultural heritage in 2015, drumming and spirit conjuring took centre stage.69

This all culminated in 2021 when UNESCO, following an application by Danish Minister of Culture Mette Bock,70 decided to include Inuit drum dancing and singing on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Daniel Thorleifsen, director of the Greenland National Museum and Archives, noted that it was ‘a bit of an irony’ that this happened during the tricentenary of the start of the Danish Christian mission, the very force that pushed drum dancing out of the public square for centuries.71 Tensions between the Church of Greenland and the rising Inuit spiritual revival came to a head in 2022 in a scandal involving one of its priests.

Markus E. Olsen (b. 1966) is a politician, educator, theologian, and alternative therapist who began his work as a parish priest in the Church of Greenland in August 2021. Influenced by the fusion of faith and political activism in the Liberation Theology school of thought and by US civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X,72 his path to priesthood was a winding one, taking him through various roles in education, business, event management, and thought field therapy,73 but his work for the church would ultimately be cut short, lasting less than a year. On 21 June 2022, Greenland’s National Day, Olsen, who is the brother of Inuit Ataqatigiit party politician Peter Olsen, led a church service in the wooden nineteenth-century Church of our Saviour in the old colonial heart of Nuuk that was broadcast over KNR radio. This service differed from the Lutheran state church’s liturgical standards in two important ways: Olsen did not pray for the Danish royal family or the Greenlandic government, and at the conclusion of his sermon he invited Leif Immanuelsen to perform a drum dance. The content of the sermon itself was also controversial, as Olsen touched on subjects like the suppression of drum dancing, the ‘Little Danes’ experiment of the 1950s (in which Greenlandic children were taken from their parents and raised in Denmark), and the aforementioned Spiral Case of the 1960s, arguing that Greenlanders should be less ‘compliant’ with the state and more willing to condemn the wrongs of the Danish authorities.74

Two days later, Olsen was suspended pending an investigation.75 His travails quickly became one of the leading news stories in Greenland, as journalists and readers sought clarification as to the exact reasons for his suspension. Greenlandic news service Sermitsiaq interviewed Knud Møller, a member of the Nuuk parish council, who informed them that ‘there is a majority in the parish council who do not approve of the priest’s use of the drum and see it as a violation of the rules for how a church service should take place’, though Møller and ‘at least one other parish council member’ supported Olsen’s decision.76

A community leader from the congregation in Tasiilaq who heard the sermon on the radio told KNR, a Greenlandic broadcast and news service, that she was overjoyed hearing Olsen preach, saying that his ‘cool’ style might ‘attract more younger churchgoers’. However, KNR’s investigations found that the point at issue was not the use of the drum per se, but Olsen’s failure to ask permission to make changes to the order of service from the parish council and the Bishop of Greenland, Paneeraq Siegstad Munk.77 A Nuuk parish council meeting concluded that there was no reason in principle that drum dancing could not take place in church, but that permission must be sought.78

Many were unsatisfied with this distinction. An online petition calling for Olsen’s reinstatement garnered over 750 signatures in just a few days after its launch in mid-July, as signatories called for ‘spiritual unity’ in Greenland, complained that the church was ‘too ingrained in old customs’, and said that it was time for the church to ‘find a solution in relation to [the incorporation of] old traditions, which are what is special about us’.79 Others wished the church would stop being ‘so square’.80 with the organiser of the petition, Dorthea Isaksen, saying that the rigidity of the church had contributed to Christianity becoming ‘very distant from people in modern-day Greenland’.81 The petition soon passed 1,000 signatures. Finally breaking his silence on 22 July, Olsen himself said that he was simply exercising his ‘independence as a pastor’ and that he ‘expected there would be consequences’ for his idiosyncrasy, ‘but not something like getting fired in 1, 2, 3 without any conversation’, while on the subject of mentioning the Danish royal family he asked why this should be a requirement in Greenland when many priests in Denmark itself are not obliged to mention the royals in their services.82 Some of his parishioners, he said, had ‘expressed gratitude that I combined our culture and our faith in a service’. On the same day, the Church clarified that the issue was indeed Olsen’s failure to ask for permission to make these changes, although it added that his strident calls for ‘Inuit to fend for themselves’ also fell outside acceptable bounds.83

Some of those who publicly denounced Olsen likewise highlighted the political content of the sermon — for instance, Henriette Have, formerly a pastor in Qasigiannguit, believed that it was accusatory in tone, its message being delivered ‘violently and brutally’, and therefore was not becoming of a Christian priest.84 Meanwhile, Leif Immanuelsen, the drum dancer whose performance helped start the whole affair, refused to come to Olsen’s aid because he disagreed with the mixing of politics and church affairs — and because, in any case, he views the church as an ‘imported’ institution that ‘does not fit into the Greenlandic culture’.85

Olsen ultimately announced in August that he would resign from the church at the end of November 2022.86 On 18 August, around 60 people participated in a public demonstration in Nuuk against the church’s treatment of the embattled priest, forming a circle near the Katuaq cultural centre while Kaaleeraq Møller Andersen performed on the qilaat.87 Organiser Paninnguaq Heilmann believed that Olsen’s sermon was rekindling ‘the younger generation’s interest in the church and Christianity’, and elaborated: ‘I think it is sad that we are losing such an important person, someone we need in the country. His sermons are spot on and are relevant to society. I also think that there should be room for everyone in the church, regardless of religion and politics.’88 For now, however, the issue was dead in the water. Olsen returned to civilian life and politics, briefly serving as one of Greenland’s two representatives in the Danish Folketinget in September-October 2023, covering for the Siumut party’s Aki-Matilda Høegh-Dam, and in a speech delivered in Greenlandic he again condemned the actions of the Danish state in the Spiral Case and declared that ‘even in our own country we [Greenlanders] are treated like foreigners’.89

Some of those who have grown weary of the rigidity of the Lutheran church experience and long for a more kinetic and lively form of spirituality have turned to New Life Church/Inuunerup Nutaap Oqaluffia (INO), a network of Pentecostal and evangelical churches that boasts the second-largest congregation after the Church of Greenland. Anthropologists Frédéric Laugrand and Jarich Oosten argue that the relative popularity of INO owes partly to the fact that the Pentecostal and charismatic practices of spiritual healing, speaking in tongues, and exorcisms for demonic possession resemble and give legitimised expression to Inuit shamanic traditions.90 Chris Shull, an American Baptist missionary who has led a church in Ilulissat since 2007, expressly discourages Pentecostal styles of worship in his congregation for precisely this reason, believing that they are too reminiscent of a pantheistic and animistic urge that still ‘lurks in the culture’.91

A tale of two statues

Whereas efforts to introduce shamanic implements into the church have so far proved ineffectual, the transformation of the built environment is, slowly but surely, under way. Erected in the 1920s on a hill overlooking the old colonial heart of Nuuk, the statue of the Lutheran missionary Hans Egede, decked in in priest’s robes and holding a Bible and a staff, has been among the capital city’s most noticeable sculptures for a century, reminding all who look upon it of the circumstances behind Nuuk’s founding. The prominence of the statue makes it an obvious target for anti-colonial protests; vandalism is therefore a consistent threat. In May 2012, the statue was sprayed with blood-like red paint, and the number ‘666’ was written on the base.92 In April 2015, feminist symbology, including the symbol of Venus (♀), was sprayed in gold paint on the statue, along with the Kalaallisut word utsuk (‘cunt’).93

On 21 June 2020, Greenland National Day, Egede was again targeted with red paint, this time in the shape of traditional Inuit tattoos, along with the English word ‘decolonize’ in white,94 and in March 2022 the words ‘Live, laugh, land back’ were written in English on the base, ‘land back’ being a phrase used by indigenous rights campaigners to demand the return of colonised land.95 Those charged by the police for these acts were all young; most were in their 20s or 30s, while at least one was a teenager. A referendum on the future of the statue — whether it should stay or go — was held in the Sermersooq Municipality (in which Nuuk is located) in July 2020, during the height of the global anti-racist and anti-colonial Black Lives Matter movement. While voters favoured its remaining by 921 votes to 600,96 the debate is certainly not over, with campaigners for it removal like the Inuit tattoo artist Paninnguaq Lind Jensen promising to ‘raise the issue again in the future’.97 Given the divisive nature of the man, many planned events commemorating the 300th anniversary of Egede’s arrival in 2021 were cancelled.98

Whatever happens with the statue, Hans Egede is no longer the sole centre of attention in the vicinity, as in September 2007 another sculpture was unveiled just 100 metres away. Designed by the artist Christian Rosing, the new statue depicts the Mother of the Sea, Sassuma Arnaa, in a scene from the Inuit legends. Sitting naked, she has long, voluminous hair in which the creatures of the sea — various fish, a polar bear, a walrus, a seal, a narwhal — are entangled, thus withholding their meat and materials from the Inuit. A young angakkoq, the Blind One, leans into this tableau to comb Sassuma Arnaa’s hair, releasing the creatures so that they can be hunted. The statue is situated such that it is submerged at high tide and visible at low tide. At the reveal ceremony, artist and politician Maliinannguaq Marcussen Mølgaard explained the meaning of the legend: ‘that humans should live with respect for nature and animals … because there is climate change and pollution of nature around the world today, and that we as humans must live by the message from the Mother of the Sea, otherwise she may go mad and hold back the animals from being caught, and humans will starve.’99

In an interview in 2021, Rosing described himself as a ‘supernaturalist’, and, detailing his reasons for making the angakkoq a young man rather than the old man that most would imagine, he said: ‘One must remember that a soul has a constant age, and that a soul is reusable. If a man and a woman who have been the same age die 30 years apart, then they will be the same age and young when they meet in the afterlife.’ On his artistic process, Rosing stated that sometimes he gets such clear visions that it is as if they come from ‘a previous life’.100 The casual nature of his explanation demonstrates the extent to which Inuit spiritualism had been normalised in modern Greenland. The shamanic revival had well and truly hit the mainstream.

The ‘comeback’

By January 2022, it was possible for Sermitsiaq and A/G to report that shamanism was ‘making a strong comeback’. To illustrate the point, they told the story of Aviaja Rakel Sanimuinaq Kristiansen, then 38, who was described as ‘a modern angakkoq … from a shamanistic lineage’. Originally from the remote East Greenlandic settlement of Ittoqqortoormiit, Kristiansen moved around in Denmark and Greenland until settling in the centre of Nuuk. Her mother, Therecie Sanimuinaq Pedersen, being raised in the ‘old-fashioned way’, says she was chosen by her family to be an angakkoq after her sister, who was originally intended for the role, was ‘scared out of her wits by the church’s scare campaign [saying] that shamanism was evil, so [that] when helpers from the spirit world came to her, she simply fled out a window’. Pedersen thus took the mantle. Now, the two have tunniit tattoos and practice Inuit shamanism daily ‘without fear of reprisals’. Kristiansen is insistent that it is a practical skill rather than a faith in the usual sense: ‘Shamanism is a method. It is not a belief, which is often misunderstood.’101

In line with her emphasis on practical application, she became a working angakkoq, with her house serving as a clinic for shamanistic sessions with clients, adorned with implements from Inuit culture: a tallow lamp, bird feathers, animal skulls, a polar bear skin, and of course qilaat drums. As an angakkoq, she uses the stand-alone name Rakel, because ‘Rakel is this part of the soul that does everything I don’t do. Aviaja disappears. I become nothing so that the higher powers can come.’ Though many in Greenland remain sceptical of her abilities, Rakel sees an average of four clients a day, mostly Greenlanders but also travellers from places like the USA, Australia, and Nunavut, with whom she ‘goes on drumming journeys to the spiritual world’, establishing contact with ancestors and undergoing healing work. She is cagey about how exactly she became an angakkoq, saying she had to learn it ‘blind’, but she is convinced of the effectiveness of her methods: ‘The body, mind and soul are connected. Soul is energy, and to create balance, the soul needs its full power. Shamanism helps to clean up oneself, one’s own inner self, using this altered state of mind, which gives one access to one’s own subconscious and superconsciousness. Having access to the two parts allows one to find balance within oneself.’102 Like other angakkuit today, Rakel uses social media platforms like Instagram to spread the word about shamanism.103

In August 2022, KNR reported on the story of Helene Naduk Kavigak Munck, then 27, who was raised in Denmark by her mother Gaz Zaa Lung, from Qaanaaq. Like the pair in Nuuk, mother and daughter practice together, using the qilaat and singing songs in Inuktun (a language of the Polar Inuit). Munck said that when she plays the drum she feels ‘a deep peace and connection with my family and my ancestors. It is a way to get in touch with the part of me that is from Greenland and my Greenlandic family.’ She explained further that it ‘means a lot to represent North Greenland and our culture, because we are a minority compared to the rest of Greenland. It is important to maintain the culture so that it does not become extinct.’ Munck and her mother were set to perform at the ‘Greenland in Tivoli’ cultural festival in Copenhagen for the second year in a row.104 The prominence of women is an unavoidable facet of this latest wave of Inuit spiritual revivalism, and can partly be explained by the sense of liberation that it can give in a once highly male-dominated society. For many, the old colonial regime that stamped out shamanism stands for a restrictive gender hierarchy, but in the shamanic tradition, ‘suddenly the Inuit woman gets a role that is very strong’, as one of Sidse Birk Johannsen’s interviewees put it.105

Trump’s gambit

Early in 2025, US president Donald Trump resuscitated an idea briefly raised during his first term in 2017–2021 — a US acquisition of Greenland through purchase or perhaps other means106 — momentarily putting Greenland at the centre of global attention. Journalists from across the world flocked to the island to interview locals and find interesting stories that would give readers a sense of life in the sparsely-populated Danish territory.

One of these journalists, Luis Andres Henao, wrote a series of articles for the Associated Press on the religious landscape in Greenland, including one titled ‘Greenlanders embrace pre-Christian Inuit traditions as a way to proudly reclaim ancestral roots’. The star of the show was once again Rakel and her clinic in Nuuk. The first thing Henao noticed was the sign outside her clinic, reading ‘Ancient knowledge in a modern world’ — inside, Rakel told him about her views on Christianity and other religions: ‘The sacredness of Christianity is still sacred in my eyes. But so is Buddhism, so is Hinduism, and so is my work.’ Her goal, she said, is to contribute to ‘the arising of our culture’ and to show that Inuit culture ‘is legit; that it has to have a space here’. Henao also spoke to the musician Naja Parnuuna, daughter of Markus Olsen, who said she wanted to ‘be in that wave with my fellow young people’ as they brought back the spiritual culture of their ancestors.107

The unwanted attention of the US president has only accentuated shamanism’s potential as a well of anti-colonial symbolism, giving it a new significance for a country that is known by the rest of the world mostly for its geopolitical situation and its natural resources. As ever, the qilaat acts as the totemic representation of Greenland’s will to self-determination and its rejection of foreign domination, be it Danish or American. Many protestors at a large demonstration against Trump’s designs on Greenland in March 2025 brought along their qilaat, while groups of drum dancers established the rhythm and coloured the soundscape of the event. As KNR reported: ‘The sound rolled out across the square, like a deep, shared pulse, and set the demonstration in motion.’108 The revival is most definitely not over.

Notes

- B. Sonne, Worldviews of the Greenlanders: An Inuit Arctic perspective (Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2018), pp. 234-6. ↩︎

- E. L. Jensen, ‘Memories of the past’, in E. L. Jensen, K. Raahauge, and H. C. Gulløv, (eds.)Cultural encounters at Cape Farewell: The East Greenlandic immigrants and the German Moravian Mission in the 19th century (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2011), pp.235-41. ↩︎

- M. Lidegaard, ‘Grønlands kirke gennem tiderne’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 101, no. 1, 1 January 1961, p. 28. https://timarit.is/page/3781883 ↩︎

- ‘Solopgang ved Jakobshavn’, Grønlandsposten, vol. 1, no. 20, 24 December 1942, pp. 1-3. https://timarit.is/page/130060 ↩︎

- H. R. Olsen, ‘Er Østgrønland himmerigets forgård eller Grønlands baggård..?’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 95, no. 24, 1 December 1955, p. 6. https://timarit.is/page/3778272 ↩︎

- ‘Grønland får i marts nyt 35-øres frimærke’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 101, no. 4, 9 February 1961, p. 8. https://timarit.is/page/3782032 ↩︎

- H. R. Olsen, ‘Er Østgrønland himmerigets forgård eller Grønlands baggård..?’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 95, no. 24, 1 December 1955, p. 6. https://timarit.is/page/3778272 ; P. Brandt, ‘De ældre frem, tager stadig trommen når de er til fest’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 97, no. 2, 31 January 1957, p. 5. https://timarit.is/page/3778989 ↩︎

- P. Brandt, ‘De ældre frem, tager stadig trommen når de er til fest’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 97, no. 2, 31 January 1957, p. 5. https://timarit.is/page/3778989 ↩︎

- ‘De klipper hinanden’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 100, no. 23, 10 November 1960, p. 13. https://timarit.is/page/3781739 ↩︎

- ‘Grønlands Grundtvig fylder 80 år’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 101, no. 10, 4 May 1961, p. 11. https://timarit.is/page/3782194 ; ‘Organist Jonathan Petersen’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 126, no. 20, 14 May 1986, p. 25. https://timarit.is/page/3816194 ↩︎

- ‘At gøre en Tupilak levende er en besværlig proces’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 104, no. 2, 16 January 1964, p. 18. https://timarit.is/page/3784288 ; ‘Angakokken Nayatok, der skaffede forår’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 105, no. 8, 14 April 1965, p. 24. https://timarit.is/page/3785336 ↩︎

- J. Lyberth, ‘Grønlandske før-kristne trosforestillinger i nutiden: Synkretistiske trostræk og- tendenser i det nyreligiøse felt i Grønland’, Master’s project, University of Copenhagen, 2015, pp. 23-4. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/issues/indigenouspeoples/sr/cfis/indigenous-freedom-religion/subm-indigenous-freedom-religion-ind-juaaka-lyberth-input-5.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Grønlandske trommesange er nu udødeliggjorte’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 105, no. 20, 30 September 1965, p. 15. https://timarit.is/page/3785733 ↩︎

- J. G. Oosten, ‘Male and female in Inuit shamanism’, Études Inuit Studies, vol. 10, nos. 1-2, 1986, pp. 125-6. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42869540 ↩︎

- S. Arnfred and K. B. Pedersen, ‘From female shamans to Danish housewives: Colonial constructions of gender in Greenland, 1721 to ca. 1970’, NORA – Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, vol. 23, no. 4, 2015. pp. 283-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740.2015.1094128 ↩︎

- N. D. Graugaard, V. E. P. Sørensen, and J. L. Stage, ‘Colonial reproductive coercion and control in Kalaallit Nunaat: Racism in Denmark’s IUD program’, NORA – Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, published online, pp. 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740.2024.2427817 ↩︎

- E. L. Jensen, ‘The East Greenlanders in new conditions’, in Jensen, Raahauge, and Gulløv,Cultural encounters at Cape Farewell, pp. 209-20. ↩︎

- Arnfred and Pedersen, ‘From female shamans to Danish housewives’, pp. 296-300. ↩︎

- D. W. Norman, ‘Summertime politics: Cultural resurgence, resource sovereignty, and the Aasivik movement’, Études Inuit Studies, vol. 47, nos. 1-2, 2023, pp. 189-213. https://doi.org/10.7202/1113389ar ↩︎

- S. H. Abelsen, ‘Bevaring og genoplivning af immaterielt kulturarv i Grønland: Qilaatersorneq, trommedans’, Bachelor’s project, University of Greenland, 2023, p. 19.. https://da.uni.gl/uddannelse/afgangsprojekter/ ↩︎

- S. B. Johannsen, ‘Revitalisering af inuitisk tradition i Grønland: Etnopartikulær nichereligion eller New Age-tendens med globalt udsyn’, Religionsvidenskabeligt Tidsskrift, vol. 73, 2022, pp. 47-8. https://doi.org/10.7146/rt.vi73.127163 ↩︎

- ‘Tukak Teatret skal til Canada næste år’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 118, no. 41, 19 October 1978, p. 26. https://timarit.is/page/3800023 ; ‘Deres danse var spændende’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 119, no. 51, 20 December 1979, p. 12. https://timarit.is/page/3801934 ↩︎

- M. M. F. Holm and J. Lyberth, ‘Trommedans var gemt og glemt, men hyldes i dag af UNESCO’, KNR, 15 December 2021. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/trommedans-var-gemt-og-glemt-men-hyldes-i-dag-af-unesco ↩︎

- ‘Indiansk skuespil’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 134, no. 68, 6 September 1994, p. 8. https://timarit.is/page/3839236 ; J. Motzfeldt, ‘Min kære sommer’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 134, no. 81, 11 October 1994, p. 12. https://timarit.is/page/3839532 ↩︎

- L. Danis, ‘Silamiut theater’, Icelandic Times, 21 November 2016. https://icelandictimes.com/silamiut-theater/ ↩︎

- ‘»Stop en halv« med Silamiut – stor succes hos publikum’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 129, no. 48, 3 May 1989, pp. 6-7. https://timarit.is/page/3822833 ↩︎

- ‘Man glemmer aldrig at Manø vrere en kajak’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 138, no. 80, 15 October 1998, p. 13. https://timarit.is/page/3850442 ↩︎

- ‘Pauline elsker trommedans’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 130, no. 128, 5 November 1990, p. 16. https://timarit.is/page/3827288 ↩︎

- ‘Vores kulturarv er vores styrke’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 132, no. 11, 27 January 1992, pp. 10-11. https://timarit.is/page/3831267 ↩︎

- ‘Grønlandsk kultur’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 132, no. 778 July 1992, p. 8. https://timarit.is/page/3832707 ↩︎

- ‘Flot udstilling på Landsbiblioteket’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 137, no. 97, 2 September 1997, p. 13. https://timarit.is/page/3847286 ↩︎

- S. H. Abelsen, ‘Bevaring og genoplivning af immaterielt kulturarv i Grønland: Qilaatersorneq, trommedans’, Bachelor’s project, University of Greenland, 2023, p. 21. https://da.uni.gl/uddannelse/afgangsprojekter/ ↩︎

- M. D. Jakobsen, Shamanism: Traditional and contemporary approaches to the mastery of spirits and healing (Oxford: Berghahn Books, 1999), p. viii. ↩︎

- Johannsen, ‘Revitalisering af inuitisk tradition i Grønland’, p. 56. ↩︎

- K. Kjærgaard, ‘Religious education, identity and nation building – the case of Greenland’, Nordidactica – Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, no. 2, 2015, pp. 118-25. ↩︎

- J. Andersen and S. Petersen, ‘Trommesang på skemaet’, KNR, 24 February 2012. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/trommesang-p%C3%A5-skemaet ↩︎

- P. Troelsen, ‘Grønlandsk kultur på skemaet i Sisimiut’, KNR, 10 April 2013. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/gr%C3%B8nlandsk-kultur-p%C3%A5-skemaet-i-sisimiut ↩︎

- A. Rytoft, ‘Trommedans i 3. klasse’, Sermitsiaq, 13 November 2022. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/trommedans-i-3-klasse/510140 ↩︎

- L. Josefsen, ‘Ny børnebog: Aqipi tager på ånderejse’, Sermitsiaq, 20 March 2018. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/ny-bornebog-aqipi-tager-pa-anderejse/252691 ↩︎

- Johannsen, ‘Revitalisering af inuitisk tradition i Grønland’, p. 48. ↩︎

- V. Sørensen, ‘Den grønlandske tromme diskriminerer ikke’, Sermitsiaq, 30 May 2014. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/den-gronlandske-tromme-diskriminerer-ikke/464142 ↩︎

- S. H. Abelsen, ‘Bevaring og genoplivning af immaterielt kulturarv i Grønland: Qilaatersorneq, trommedans’, Bachelor’s project, University of Greenland, 2023, p. 20. https://da.uni.gl/uddannelse/afgangsprojekter/ ↩︎

- Z. Vilikovská, ‘Zvolen welcomed UN Representative of Arctic Peoples from Greenland’, The Slovak Spectator, 3 November 2014. https://spectator.sme.sk/politics-and-society/c/zvolen-welcomed-un-representative-of-arctic-peoples-from-greenland ↩︎

- ‘Angaangaq’, IceWisdom, as of 24 April 2025. https://icewisdom.com/angaangaq-angakkorsuaq/ ↩︎

- A. Bracci, ‘Interview to Angaangaq Angakkorsuaq’, Associazione Nazionale Ecobiopsicologia, March 2021. https://www.aneb.it/interview-to-angaangaq-angakkorsuaq/ ↩︎

- ‘Icewisdom – the ice is speaking’, IceWisdom, as of 24 April 2025. https://icewisdom.com/icewisdom/ ↩︎

- G. Ehegartner, ‘The ice in people’s hearts shall melt’, NatureFlowFachblatt, 31 March 2019. https://natureflowfachblatt.blog/2019/03/31/angaangaq-the-ice-in-the-hearts-shall-melt/ ↩︎

- ‘Uncle Angaangaq Angakkorsuaq’, Parliament of the World’s Religions, as of 24 April 2025. https://parliamentofreligions.org/speakers/uncle-angaangaq-angakkorsuaq/ ↩︎

- ‘En skamplet på Grønland’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 103, no. 8, 10 April 1963, p. 11. https://timarit.is/page/3783659 ↩︎

- Johannsen, ‘Revitalisering af inuitisk tradition i Grønland’, pp. 46-7, 55-6. ↩︎

- P. Pikilak, ‘Tunniit: A guide to Inuit Tattoos in Greenland’, Visit Greenland. https://visitgreenland.com/articles/a-guide-to-inuit-tattoos-in-greenland/ ↩︎

- Johannsen, ‘Revitalisering af inuitisk tradition i Grønland’, pp. 53-4. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 48. ↩︎

- H. L. Nolsø, ‘Trommen i den grønlandske Folkekirke? – Konflikten mellem kristendommen og inuits religion og kultur i Tasiilaq og Nuuk i teologisk, historisk og nutidigt perspektiv’, Bachelor’s project, University of Greenland, 2020, p. 17. https://da.uni.gl/uddannelse/afgangsprojekter/ ↩︎

- Lyberth, ‘Grønlandske før-kristne trosforestillinger i nutiden’, pp. 38-9. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 42-3. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 33-7. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 28-32. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 46-7. ↩︎

- A. Ringgaard, ‘Kristendom og spøgelsestro lever side om side i Grønland’, Videnskab.dk, 3 August 2016. https://videnskab.dk/kultur-samfund/kristendom-og-spoegelsestro-lever-side-om-side-i-groenland/ ↩︎

- Lyberth, ‘Grønlandske før-kristne trosforestillinger i nutiden’, p. 58. ↩︎

- A. Osborn, ‘“Cleansed” Greenland cabinet falls’, The Guardian, 11 January 2003.http://theguardian.com/world/2003/jan/11/andrewosborn ; J. Olsen, ‘Greenland official fired after using Inuit healer’, The Independent, 14 January 2003. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/greenland-official-fired-after-using-inuit-healer-123756.html ↩︎

- Lyberth, ‘Grønlandske før-kristne trosforestillinger i nutiden’, p. 59. ↩︎

- H. Broberg, ‘Gudstjeneste med trommedans’, Sermitsiaq, 16 September 2012. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/gudstjeneste-med-trommedans/244998 ↩︎

- Nolsø, ‘Trommen i den grønlandske Folkekirke?’, p. 23. ↩︎

- N. K. Søndergaard, ‘Trommedanser rørt efter hæder’, Sermitsiaq, 6 February 2016. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/trommedanser-rort-efter-haeder/390789 ↩︎

- R. Langhoff, ‘Anna Kûitse Thastum er død’, Sermitsiaq, 13 July 2012. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/anna-kitse-thastum-er-dod/486102 ↩︎

- ‘TELE-POST giver den fuld gas med frimærker i 2014’, KNR, 17 December 2013. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/tele-post-giver-den-fuld-gas-med-frim%C3%A6rker-i-2014 ↩︎

- ‘Billeder: Kulturhistoriske optrædener i Maniitsoq’, Sermitsiaq, 8 March 2015. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/billeder-kulturhistoriske-optraedener-i-maniitsoq/374902 ↩︎

- A. P. Knudsen, ‘Trommesanger: Unesco redder vores tradition’, KNR, 8 February 2019. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/inuit-ileqqutoqaata-tammatsaaliornissaannik-pingaartitsisut ↩︎

- M. M. F. Holm and J. Lyberth, ‘Trommedans var gemt og glemt, men hyldes i dag af UNESCO’, KNR, 15 December 2021. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/trommedans-var-gemt-og-glemt-men-hyldes-i-dag-af-unesco ↩︎

- L. A. Henao, ‘Greenlanders embrace pre-Christian Inuit traditions as a way to proudly reclaim ancestral roots’, Associated Press, 23 March 2025. https://apnews.com/article/greenland-inuit-traditions-tattoos-shaman-christianity-trump-e3402e2bf207cd3486be00d2925ff5d6 ↩︎

- ‘Markus E. Olsen (SIU)’, Folketinget, 6 October 2023. https://www.ft.dk/medlemmer/mf/m/markus-e-olsen ↩︎

- Itsumarlo Parlo Studio, ‘Palasi Markus E. Olsen’, YouTube, 24 June 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g44tIGO3Ob0 ↩︎

- T. M. Veirum, ‘Præst i Nuuk suspenderet’, Sermitsiaq, 24 June 2022. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/praest-i-nuuk-suspenderet/375428 ↩︎

- T. M. Veirum, ‘Menighedsrådsmedlemmer protesterer over præste-suspendering’, Sermitsiaq, 25 June 2022. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/menighedsradsmedlemmer-protesterer-over-praeste-suspendering/158267 ↩︎

- M. Kuitse, ‘Præst fritaget for tjeneste: Menighedsrepræsentanter er splittede’, KNR, 29 June 2022. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/suspendering-af-markus-e-olsen-meninghedspr%C3%A6sentanter-har-forskellige-meninger ↩︎

- N. Hansen, ‘Menighedsråd: Der skal ansøges om brug af trommedans i kirken’, Sermitsiaq, 3 July 2022. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/menighedsrad-der-skal-ansoges-om-brug-af-trommedans-i-kirken/220568 ↩︎

- K. Platou and C. Hyldal, ‘Nu har mere end 700 skrevet under: Derfor vil vi have Markus Olsen tilbage som præst’, KNR, 19 July 2022. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/nu-har-mere-end-700-skrevet-under-derfor-vil-vi-have-markus-olsen-tilbage-som-pr%C3%A6st ↩︎

- M. Kuitse, N. Tobiassen, and M. M. F. Holm, ‘Ekspert om suspendering af præst: Der er tale om en mindre fejl, som bør udløse en mindre konsekvens’, KNR, 1 July 2022. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/oqaluffimmi-inatsisilerinermik-ilisimasalik-markus-e-olsen ↩︎

- A. G. Møller and H. V. Hviid, ‘Dorthea har startet protest: Det handler om at råbe kirken op’, KNR, 20 July 2022. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/dorthea-har-startet-protest-det-handler-om-r%C3%A5be-kirken-op ↩︎

- N. Tobiassen and C. Hyldal, ‘Landets mest omtalte præst tager ordet: Jeg har intet at miste’, KNR, 22 July 2022. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/landets-mest-omtalte-pr%C3%A6st-tager-ordet-jeg-har-intet-miste%C2%A0 ↩︎

- K. Kristensen, ‘Præst står til fyring: Trommen bliver min kirkelige undergang’, Sermitsiaq, 22 July 2022. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/praest-star-til-fyring-trommen-bliver-min-kirkelige-undergang/535431 ↩︎

- B. Nathansen and K. Platou, ‘Teolog kritiserer Markus E. Olsens prædiken: Voldsom, brutal og ukristen’, KNR, 28 July 2022. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/teolog-kritiserer-markus-e-olsens-pr%C3%A6diken-voldsom-brutal-og-ukristen ↩︎

- ‘Vores egen kulturarv’, Sermitsiaq, 4 August 2022. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/vores-egen-kulturarv/512297 ↩︎

- H. V. Hviid and K. Platou, ‘Efter stor debat: Markus E. Olsen er færdig som præst’, KNR, 12 August 2022. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/efter-stor-debat-markus-e-olsen-er-f%C3%A6rdig-som-pr%C3%A6st ↩︎

- A. Rytoft, ‘Demonstration for præst: Trommen bør accepteres i kirken’, Sermitsiaq, 19 August 2022. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/demonstration-for-praest-trommen-bor-accepteres-i-kirken/161183 ↩︎

- K. Kristensen, ‘Støtter demonstrerer for Markus E. Olsen torsdag’, Sermitsiaq, 16 August 2022. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/stotter-demonstrerer-for-markus-e-olsen-torsdag/157272 ↩︎

- T. M. Veirum, ‘Markus E. Olsen i Folketinget: Vi behandles som fremmede i eget land’, Sermitsiaq, 5 October 2023. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/markus-e-olsen-i-folketinget-vi-behandles-som-fremmede-i-eget-land/675763 ↩︎

- F. B. Laugrand and J. G. Oosten, Inuit shamanism and Christianity: Transitions and transformations in the twentieth century (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010), pp. 342-71. ↩︎

- J. Duin, ‘The pastor at the top of the world’, Newsweek, 20 October 2021. https://www.newsweek.com/pastor-top-world-1640942 ↩︎

- S. D. Duus, ‘Hans Egede-statue vandaliseret’, Sermitsiaq, 14 May 2012. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/hans-egede-statue-vandaliseret/180557 ↩︎

- ‘Politiet søger vidner efter statue-vandalisering’, Sermitsiaq, 7 April 2015. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/politiet-soger-vidner-efter-statue-vandalisering/367876 ↩︎

- A. M. Synnestvedt, ‘To mere er sigtet for hærværk på Hans Egede-statue’, KNR, 6 July 2020. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/mere-er-sigtet-h%C3%A6rv%C3%A6rk-p%C3%A5-hans-egede-statue ↩︎

- K. Kristensen, ‘Hans Egede-statue overmalet med rød igen’, Sermitsiaq, 25 March 2022. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/hans-egede-statue-overmalet-med-rod-igen/201427 ↩︎

- C. Hyldal, ‘Afstemning om Hans Egede er slut: Flertal sømmer statue fast til fjeldtop’, KNR, 22 July 2020. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/afstemning-om-hans-egede-er-slut-flertal-s%C3%B8mmer-statue-fast-til-fjeldtop%C2%A0 ↩︎

- M. Brøns, ‘Modstander af statue: Godt at vi fik startet en debat’, KNR, 23 July 2020. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/modstander-af-statue-godt-vi-fik-startet-en-debat ↩︎

- M. M. F. Holm, ‘Egede de sidste 100 år: Hyldet og halshugget’, KNR, 10 July 2021. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/egede-de-sidste-100-%C3%A5r-hyldet-og-halshugget ↩︎

- O. I. Olsen, ‘Havets moder afsløres’, KNR, 25 September 2007. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/havets-moder-afsl%C3%B8res ↩︎

- K. Larsen, ‘Christian “Nuunu” Rosing still going strong’, Sermitsiaq, 4 April 2021. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/christian-nuunu-rosing-still-going-strong/641047 ↩︎

- ‘Moderne angakkoq: – Jeg er ikke død’, Sermitsiaq, 30 November 2022. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/moderne-angakkoq-jeg-er-ikke-dod/221438 ↩︎

- A. G. Møller, ‘Aviaja Rakel arbejder som angakkoq: Har aldrig oplevet så stor opmærksomhed’, KNR, 6 April 2023. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/har-aldrig-oplevet-saa-stor-opmaerksomhed ↩︎

- ‘Shaman om danskerne: »I tænker alt i kasser, men I har stadig en sjæl«’, Jyllands-Posten, 23 July 2023. https://jyllands-posten.dk/indland/ECE16293524/shaman-om-danskerne-i-taenker-alt-i-kasser-men-i-har-stadig-en-sjael/ ↩︎

- A. G. Møller, ‘Helene Naduk trommedanser med sin mor: Jeg oplever en forbundethed’, KNR, 3 August 2022. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/helene-naduk-trommedanser-med-sin-mor-jeg-oplever-en-forbundethed ↩︎

- Johannsen, ‘Revitalisering af inuitisk tradition i Grønland’, p. 56. ↩︎

- I. Aikman, ‘Trump says he believes US will “get Greenland”’, BBC News, 26 January 2025. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/crkezj07rzro ↩︎

- L. A. Henao, ‘Greenlanders embrace pre-Christian Inuit traditions as a way to proudly reclaim ancestral roots’, Associated Press, 23 March 2025. https://apnews.com/article/greenland-inuit-traditions-tattoos-shaman-christianity-trump-e3402e2bf207cd3486be00d2925ff5d6 ↩︎

- M. M. F. Holm, ‘Nok er nok! Folket gav Trump den kolde skulder’, KNR, 17 March 2025. https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/nok-er-nok-folket-gav-trump-den-kolde-skulder ↩︎