Illustration of Eirik the Red from a seventeenth-century Icelandic vellum.

- The testament of the sagas

- The testament of the artefacts

- The testament of the historians

- Big claims, limited data

- Notes

Histories of medieval European colonisation in the North Atlantic tend to privilege the experiences of Norse settlers – the ‘Vikings’ who established long-lasting farming communities in Iceland in the ninth century and Greenland in the tenth century. In the case of Iceland, it has long been known by historians that communities of Irish monks, known as the Papar, resided there for decades before the Norse arrived,1 but where Greenland’s early history is concerned the Norse remain the focus of attention, and rumours about the presence of other people from Europe are given little credence. That Norse settlers were the first Europeans to live there is, broadly, uncontroversial.

The reason for this is fairly simple: the textual and archaeological evidence for pre-Norse settlement and Christianisation in Greenland is, on the whole, not very strong, consisting of a few passing mentions in medieval documents and some circumstantial material found at Norse excavation sites. Any theory asserting this notion thus relies on a hefty dose of inference. Still, given their endurance for over a thousand years and the tantalising nature of some of the source texts, it is worth discussing these theories in depth.

The testament of the sagas

The standard narrative on the European settlement of Greenland starts with the stories recorded in the Icelandic sagas, most of all the Saga of Eirik the Red and the Saga of the Greenlanders.2 As the name of the former suggests, these stories focus on the life of one Eirik the Red, who left Iceland for Greenland in 982 CE and proceeded to establish colonies with his progeny and followers around 985 or 986.

The pioneers were mostly followers of the old Norse gods, but when Leif Eiriksson (i.e., Eirik’s son) sailed back to Norway during the reign of Óláf Tryggvason (995-1000), the king told him: ‘you will go as my envoy to convert Greenland to Christianity’. Leif warned that the Gospel ‘would meet with a harsh reception in Greenland’, but the king insisted that there was ‘no man more suitable for the job than Leif’, and so the dragooned young missionary departed the king’s court for his adopted homeland and ‘began to advocate Christianity and the true catholic faith throughout the country, revealing the messages of King Óláf Tryggvason to the people, and telling them how excellent and glorious the faith was’. Though Leif’s father Eirik resisted, his mother, Þjóðhildur (Thjodhild), converted to the faith and built Greenland’s first Christian church, a small personal chapel in Brattahlíð/Narsarsuaq.3

Both sagas are equivocal on the pace and extent of Christianisation. Eirik the Red’s Saga relates that Christian burial practices were widely adopted (even if, lacking a priest, they had to wait for the burial grounds to be consecrated),4 but also says that some people ‘paid scant heed to the faith’.5 The Saga of the Greenlanders claims that Greenland ‘had been converted to Christianity’ during the settlement’s second generation and after Eirik’s death,6 but stipulates that the faith was ‘still in its infancy in Greenland’.7

There are clear signs of narrative bias throughout these stories. As historian Arnved Nedkvitne puts it, the ‘main motive’ for the authors was probably to ‘give honour to those who had participated’ in these events,8 and as they were composed in the thirteenth century at a time when Iceland was becoming much more tightly integrated with Norwegian political and ecclesiastical systems, the sagas award the most honour to the king and the Icelandic settlers. Jonathan Grove writes that Greenland as a setting in the sagas afforded Icelanders opportunities ‘to chart the parameters of Icelandic cultural self-consciousness’ and, in the sphere of religion, to construct heroic stories of Icelandic Christianity overcoming Greenlandic paganism.9

No story is ever truly ‘neutral’, and the sagas are noticeably heavy-handed in their biases, but even the sagas admit that people other than Icelanders participated in the process.

As per the sagas, Eirik was not the first European to set eyes on Greenland and its surrounding islets, as another traveller, Gunnbjörn Úlfsson, had apparently stumbled upon a collection of islands on the south Greenland coast as much as a century beforehand – these islands became known as Gunnbjörn’s Skerries.10 If this is accurate, knowledge of his discovery may have spread far beyond Iceland and Norway many decades before Eirik made his move. The colonies themselves seem to have attracted a variety of people. Among the early settlers, the Saga of the Greenlanders lists a man ‘from the Hebrides [in Scotland], a Christian’, who composed a heroic poem on the journey: ‘I ask you, unblemished monks’ tester [Christ], to be the ward of my travels; may the lord of the peaks’ pane [heavens] shade my path with his hawk’s perch [hand].’11

The Hebrides were at this time mostly populated by the Norse. Leif was blown off course to the Hebrides during his trip to Norway and met a local woman, Thorgunna, with whom he had a child named Thorgils who ‘was thought to have something preternatural about him’, and who later came to Greenland.12 Leif also found himself at the mercy of the winds on his homeward journey and ‘chanced upon land where he had not expected any to be found’, encountering there a group of ‘men clinging to a ship’s wreck, whom he brought home’. The saga states briefly that Leif ‘converted [this] country to Christianity’.13 Whoever these men were, they joined Leif’s party.

Later, the saga retroactively adds a curious detail to its account of Leif’s meeting with the king:

When Leif had served King Óláf Tryggvason and was told by him to convert Greenland to Christianity, the king had given him two Scots, a man named Haki and a woman called Hekja. The king told him to call upon them whenever he needed someone with speed, as they were fleeter of foot than any deer.

Haki and Hekja were the first to make land when Leif undertook his infamous expedition to ‘Vinland’ somewhere on the east coast of North America, probably Newfoundland.14 Another Icelandic text by the monk Oddr Snorrason, Heimskringla (ca. 1230) states that when Leif left Norway to return to Greenland, he ‘brought with him a priest and teachers’ whom the king had brought from England. Snorrason notes that the Greenlanders were not very impressed by the rhetorical abilities of these ministers,15 but it is significant that the sagas acknowledge foreign involvement.

The testament of the artefacts

Archaeological data also attests that there was some level of Celtic British influence in the religious lives of the settlers. Christian Keller argued in his 1989 PhD thesis at the University of Oslo that while the church architecture found in Greenland largely follows the Norwegian model, the preference of the builders for rounded courtyard/cemetery walls seems to be more reminiscent of Celtic British styles, and is not clearly paralleled in any known Norwegian church ruins from the period.16 This phenomenon could, in the words of Lesley Abrams, ‘reflect a combination of religious influences in the new community right from the start’,17 but it does not necessarily contradict the sagas.

Nedkvitne believes that some of the settlers may have simply seen this style of wall while travelling in the British Isles, or that the English ministers sent by Óláf Tryggvason could have been responsible for the architectural import. Inspiration came from many sources. For example, Nedkvitne states that some of the early Norse churches in Greenland are ‘modelled on an Anglo-Saxon pattern’ in which the chancel (containing the altar and choir area) is narrower than the nave (the long ‘front’ wing), possibly at the instigation of elites in Greenland who wished to display their wealth. Nedkvitne thus concludes that the walls ‘cannot be used as empirical evidence that Celtic missionaries sailed to Greenland directly from the British Isles, nor that religious ideas which were specifically Celtic found their way to Greenland’.18

On their own, the rounded walls constitute insufficient data from which to build a new historical narrative in which British colonists, missionaries, and cultural norms take the lead. Beyond the walls, no artefacts can easily be construed as evidence of a pre-Norse stage of colonisation. Possible British influences on the design of Greenlandic crosses and crucifixes do not appear until a later Anglo-Saxon era, long after the first Norse colonies were established.19

The testament of the historians

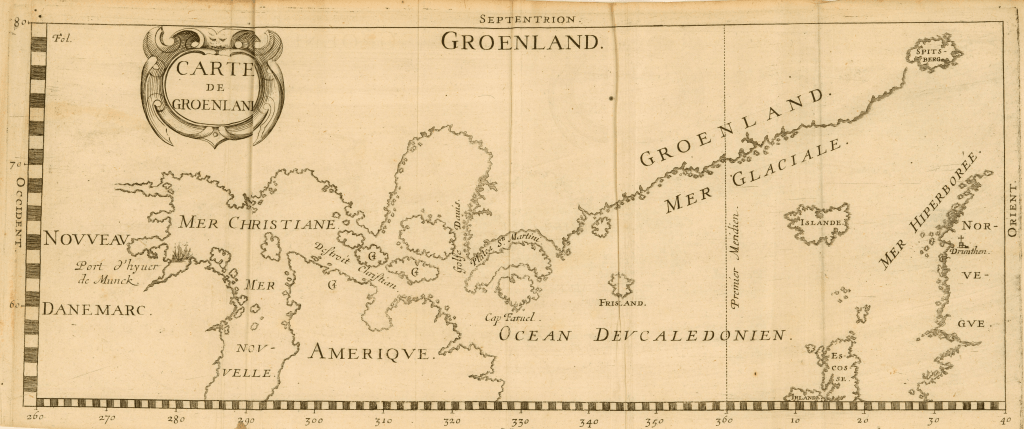

The question of the chronology of Norse Greenlandic history was given new life in the early seventeenth century during the reign of the Danish king Christian IV (1588-1648), when Danish fascination with the old Arctic territory reached new heights. In his Grønlandske Chronica (Greenland Chronicle, 1608), Danish historian Claus Christoffersen Lyschander assigned Greenland’s settlement to the year 770, basing his assessment on ‘old Antiquities and Documents’.20

The issue was also raised in two letters from the French scholar Isaac de La Peyrère to the writer and linguist François de La Mothe Le Vayer. These refer to Lyschander’s chronicle and a papal bull (written decree) issued by Pope Gregory IV in the year 835. The first of these letters, sent in December 1644 and titled ‘An account of Iceland’, comprises an overview of the geography and history of Iceland, and La Peyrère defers to Lyschander in placing the start of the Greenland settlements in 770.

La Peyrère also observed that in the early 830s the Archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen in north Germany, named Ansgar or Ansgarius, was assigned Apostle to the North, a remit that included a place called ‘Gronlandon’. He received this calling first from Louis the Pious, King of the Franks and son of Charlemagne, and then from Pope Gregory IV in his bull of 835. La Peyrère argues that by ‘inference’ one can conclude ‘that Greenland was inhabited by Christians in … 834, which agrees with my Danish chronicle, where the first discovery of Greenland is fixed to the year 770.’ He further suggests that those who rejected this version of events and clung to the saga narrative were motivated not by the search for truth but by the desire to preserve the glory of discovering and settling Greenland for the Icelanders.21

In a follow-up letter in January 1646 titled ‘An account of Greenland’ (later converted into a standalone book, Relation du Groenland), La Peyrère maintained that ‘this computation is more probable’ than the supposition that Eirik the Red was the first to settle Greenland, and added that one ‘Mr. Gunter, secretary to the king of Denmark, a person of more than ordinary learning and ingenuity, and my intimate friend’, testified that he had found in the records of the Bremen archbishopric a copy of the 835 bull.22

Lyschander’s and La Peyrère’s works continued to inspire historical curiosity during the next phase of European settlement in Greenland in the eighteenth century. Two missionaries, Hans Egede and David Crantz, wrote books in which they gave overviews of the Norse settlements using all known sources. Egede knew of Lyschander’s chronicle through La Peyrère. In his Description of Greenland (1741), Egede wrote:

A Danish Chronicle, which [Monsignor] Peyrere had consulted, refers the discovery of Greenland to a much earlier date than that which has been given upon the authority of Torfæus [an Icelandic historian and expert on the sagas]; and the earlier date of 770 is more likely to be true, if, as Peyrere mentions, there is a bull of Pope Gregory IV, in 835, relative to the propagation of the Christian faith in the North of Europe, in which Iceland and Greenland are particularly mentioned. The Danish Chronicle, to which Peyrere appeals, states, that the Kings of Denmark, having been converted to Christianity during the empire of Louis le Debonaire [or Pious], Greenland had become an object of general attention at this period.23

David Crantz’s History of Greenland (1765) contains a similar passage:

Greenland annals in Danish verse by a divine, Claudius Christophersen, or Lyscander, assign the year 770, for the true date [of the settlement of Greenland]. And this computation not only derives some countenance from the antiquities of Iceland, but is still more strongly corroborated by a Bull of Pope Gregory IV. issued in the year 835, which commits the conversion of the northern nations, and of the Icelanders and Greenlanders expressly, to Ansgarius, the first apostle of the north, who had been made archbishop of Hamburgh, by the emperor Lewis the Pious. If this Bull is authentic, which we see no reason to doubt, Greenland must have been discovered and inhabited by the Norwegians, at least as early as the year 830.24

A few modern historians remain convinced that Greenland could have been colonised and Christianised before Eirik’s and Leif’s time. Jacques Privat maintains that ‘an early Greenland Christianization that involved a Celtic presence’ cannot be ruled out in light of the propensity towards circular courtyard walls, nor can a Hamburg mission be ruled out given the ‘surprising repetition or persistence of the Hamburg bishopric’s claims’ of jurisdiction in ‘Gronlandon’, and the confirmation of this function not just by Pope Gregory IV in 835, but also by Anastasius III in 912.25 When combined with the saga narratives emphasising the initiative of King Óláf Tryggvason, this presents a picture of Greenland’s Christianisation in three distinct waves, of which Óláf’s was the latest.

As for the absence of these earlier waves in the sagas, Privat writes: ‘I have little doubt that the Nordic scribes sought to laud Scandinavian colonists and overlooked any others, and that the Celtic population doomed to disappear or be assimilated suffered the same fate in the historical records written by these Icelanders.’26 In other words, an entire phase of colonisation was written out of the story to make it more flattering to the Icelanders.

Big claims, limited data

It must be reiterated that there are no medieval documents detailing an actual mission to Greenland before the time of Eirik and Leif – they only state that responsibility for this mission field was awarded to the Archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen. It is also significant that no archaeological remains of an earlier period of non-Norse European settlement have been found. All we have is rounded walls and a few passing mentions of a place named ‘Gronlandon’ situated somewhere in the northern seas.

Place names in this remote part of the world were impermanent and prone of drift from one landmass to another because European geographical knowledge of the region was rudimentary at best. In later centuries, it became common to refer to the Spitsbergen/Svalbard archipelago as ‘Greenland’.27 Without specific archaeological data pointing to the settlement of Greenland by Europeans in the eighth or ninth centuries, theories built on these sources can only be speculative.

In a general sense, though, it is interesting that there was already a place in the northern seas called Greenland or Gronlandon before Eirik the Red, as the Icelandic sagas claim that he was the one who called the place Greenland ‘as he said people would be attracted there if it had a favourable name’.28 Even if the sagas are generally correct as to the date of Greenland’s colonisation, it is not unreasonable to postulate that this etymology of the island’s European name was mistakenly or deliberately misattributed to Eirik, or that multiple etymologies are true. Adam of Bremen’s Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontifi cum (1070s) says of Greenland: ‘The people there are greenish from the salt water, whence, too, that region gets its name.’29 It is possible that this passage preserves an older tradition explaining the island’s name.

Alternatively, we might conclude that ‘Gronlandon’ in the papal bulls refers to some other landmass, not the Greenland that we know today. Jumping from either of these solutions to a wide-ranging theory that Greenland was colonised in the 770s instead of the 980s cannot easily be justified.

Notes

- W. A. Craigie, ‘The Gaels in Iceland’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol. 31, 1897, p. 248. ↩︎

- F. Gad, The history of Greenland, vol. I: Earliest times to 1700. Translated by Ernst Dupont. (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1971), cha. 2; K. A. Seaver, The frozen echo: Greenland and the exploration of North America ca. A.D. 1000-1500 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996), pp. 14-27. ↩︎

- ‘Eirik the Red’s Saga’. Translated by K. Kunz. In Ö. Thorsson and B. Scudder (eds.), The sagas of the Icelanders (Reykjavík: Leifur Eiriksson Publishing, 1997), p. 661. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 664. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 666. ↩︎

- ‘The Saga of the Greenlanders’. Translated by K. Kunz. In Thorsson and Scudder, The sagas of the Icelanders, p. 643. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 644. ↩︎

- A. Nedkvitne, Norse Greenland: Viking peasants in the Arctic (London: Routledge, 2019), p. 16. ↩︎

- J. Grove, ‘The place of Greenland in medieval Icelandic saga narrative’, Journal of the North Atlantic, Special Volume 2, 2009, pp. 45-6. https://doi.org/10.3721/037.002.s206 ↩︎

- R. W. Rix, The vanished settlers of Greenland: In search of a legend and its legacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), p. 16. ↩︎

- ‘The Saga of the Greenlanders’. p. 636. ↩︎

- ‘Eirik the Red’s Saga’, pp. 660-1. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 661. It is not wholly clear to which ‘country’ this sentence refers. It could mean that Leif converted the land to which he was blown by the winds, or it could be a misplaced statement of his conversion of Greenland. During a subsequent trip to find this mysterious land (p. 662), the party seemingly sails eastwards (they are tossed about by the wind and come in sight of Iceland), not westwards (i.e., towards America), although they could have tried to go westwards and been pushed all the way back to Iceland by the weather. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 667. ↩︎

- Nedkvitne, Norse Greenland, pp. 83-4. ↩︎

- C. Keller, The Eastern Settlement reconsidered: Some analyses of Norse medieval Greenland, PhD thesis, University of Oslo, 1989, pp. 188, 193, and 275. ↩︎

- L. Abrams, ‘Early religious practice in the Greenland settlement’, Journal of the North Atlantic, Special Volume 2, 2009, p. 61. http://dx.doi.org/10.3721/037.002.s207 ↩︎

- Nedkvitne, Norse Greenland, pp. 85 and 105. ↩︎

- J. Arneborg, ‘Christian medieval art in Norse Greenland: Crosses and crucifixes and their European antecedents’, Scripta Islandica, vol. 71, 2020, pp. 165-6. https://doi.org/10.33063/diva-429323 ↩︎

- V. Etting, ‘The rediscovery of Greenland during the reign of Christian IV’, Journal of the North Atlantic, Special Volume 2, 2009, p. 156. https://doi.org/10.3721/037.002.s216 ↩︎

- I. de la Peyrère, ‘An account of Iceland’, in A. Churchill (ed.), Voyages and travels into Brasil and the East-Indies, vol. II (London: Awnsham & John Churchill, 1732), pp. 394-5. ↩︎

- I. de la Peyrère, ‘An account of Greenland’, in Churchill, Voyages and travels, p. 401. ↩︎

- H. Egede, A description of Greenland (London: T. and J. Allman, 1818), pp. xx-xxi. ↩︎

- D. Crantz, The history of Greenland, including an account of the mission carried on by the United Brethren in that country, vol. 1 (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1820), p. 224. ↩︎

- J. Privat, Mysteries of the far north: The secret history of the Vikings in Greenland & North America (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2023), pp. 236-7. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 238-9. ↩︎

- Gad, The history of Greenland, pp. 198 and 226. ↩︎

- ‘Eirik the Red’s saga’, p. 655. ↩︎

- Adam of Bremen, History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen. Translated by Francis J. Tschan. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), p. 218. ↩︎