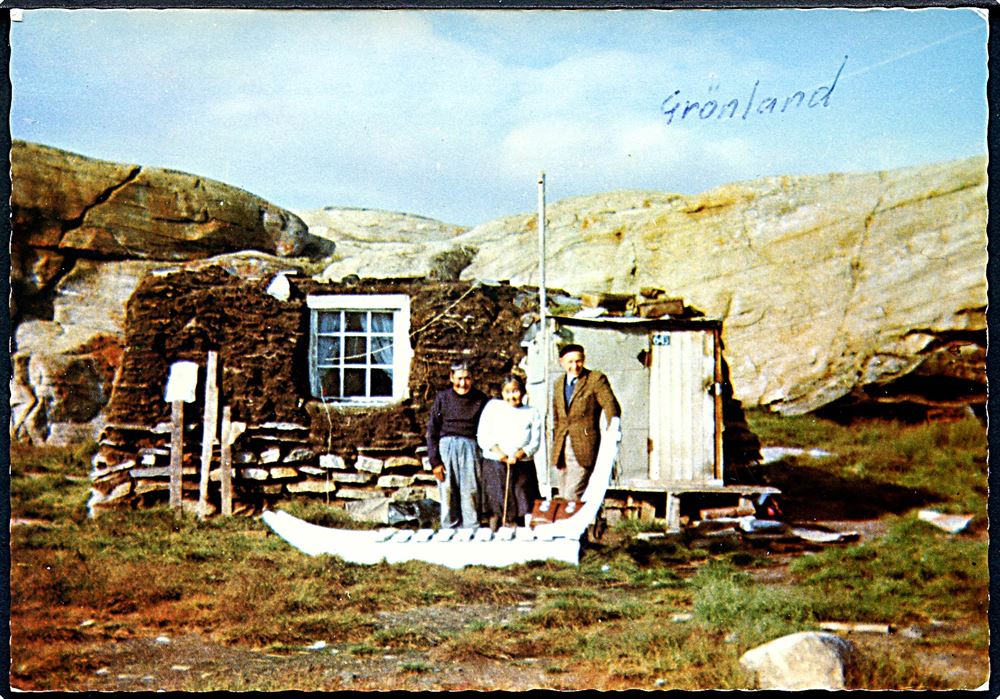

Postcard featuring Rune Åsblom (right) with a Greenland couple in Saattut, Northwest Greenland, 1975.

Among the challengers to the Lutheran Church that flooded into Greenland when the Lutheran ecclesiastical monopoly was abolished in 1953 – including Catholics, Adventists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Bahá’ís – the Pentecostal movement was one of the few that the Church viewed as a serious threat. This assessment has proved largely correct. In today’s Greenland, Pentecostal churches (allied with evangelical and charismatic churches) are some of the most successful non-Lutheran religious institutions.

Pentecostalism gets its name from the Pentecost, an event recorded in the New Testament (Acts 2:1-13). After Jesus’s death, resurrection, and ascension back into heaven, the apostles gathered in Jerusalem and ‘were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit gave them utterance’. Pentecostal Christians thus emphasise the second baptism in the life of the believer, when they are overcome with the Spirit and, they believe, gain the ability to speak in other ‘tongues’, either a non-extant language or an extant language that they did not previously know. Worship in Pentecostal churches tends to be very energetic and kinetic, with raised hands and loud proclamations from the congregation.

The Scandinavian wave (1953-2000)

One of the most significant figures in the first wave of Pentecostal evangelism in Greenland was Rune Åsblom, a former mental hospital worker and merchant skipper from Bollnäs, Sweden.1 In a 2003 interview with the Swedish Christian magazine Dagen, Gunvor Åsblom recalled that her then husband-to-be, Rune, was the first to arrive in Greenland in 1953 on a temporary decampment from his existing mission field in Iceland. Rune and Gunvor married in 1954 in Bollnäs, and later that year they returned as a couple to Greenland along with another Swedish Pentecostal couple, Erik and Gerda Martinsson. Gunvor said the newcomers ‘met with great scepticism, mainly from the Lutheran Church, which regarded [us] as heretics. But gradually we got on good terms with the priests in Greenland. With the general population, there were never any problems. Eventually we almost became Greenlanders ourselves.’

The Åsbloms lived in ‘spartan conditions’ at first, as Gunvor details: ‘It was squalid, no toilets and water, no sewage at all.’ Their material situation was made more urgent by the fact that Gunvor gave birth to five children while in Greenland, and their morale strained under the perceived hostility of the Lutheran priests. According to Dagen: ‘[T]he authorities tried to have the newly arrived Swedes expelled from the country. The Lutheran Church put a lot of energy into removing them.’ However, Gunvor told the magazine that ‘relations with the priests got better and better’ with time. Their children went to Greenlandic schools, helping the parents establish friendships with Greenlandic families.2

Rune Åsblom held his first meetings in Qaqortoq in the far south of Greenland in 1953 with the help of a local interpreter, and on their return in 1954 he and Gunvar established themselves on a permanent basis in nearby Nanortalik. The first Pentecostal mission in Godthåb/Nuuk, Greenland’s capital city, was started by the Norwegians Anne Dalen and Gudrun Ingeborg Reitung, who built their own house in 1954,3 and responsibility for work in Nuuk subsequently passed to a series of representatives from the Swedish Mission Association and the Danish branch of the Apostolic Church, many of whom did not stay for long.4

From the 1950s to the 1990s, Pentecostal mission stations were established in most of Greenland’s significant population centres, from Ilulissat in the north to Qaqortoq in the south. The missionaries themselves typically only stayed for a few years to a decade of service. They came primarily from Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Iceland, but some of the missionaries who worked in Sisimiut in the 1980s were from the United States and Canada – part of a new wave of North American missionaries whose efforts rejuvenated Greenlandic evangelicalism and Pentecostalism.

Stig Öberg, one of the Swedish Pentecostals who served in Greenland during the 1960s and 1970s, later wrote that the various missions ‘worked very independently, isolated from each other due to long distances, expensive communications and limited financial resources. The missionaries had varied backgrounds and were supported by different congregations.’ They communicated via letter or telegram, as telephone connections were not yet established between many of Greenland’s settlements. Scandinavian congregations supporting the missionaries in Greenland held annual mission conferences that alternated between Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, with the 1969 Narsaq conference being the first such event in Greenland itself.5 On the ground, the missions were small-scale operations with little interconnected oversight.

Commenting on the unfolding ‘battle for souls’ in the bilingual Greenlandic and Danish Atuagagdliutit / Grønlandsposten (A/G) newspaper in February 1955, prominent Greenlandic politician and musician Frederik Nielsen ranked the Swedish Pentecostal mission as one of the two ‘primary’ religious groups to have arrived in Greenland after 1953, the other being the Seventh-day Adventists. While these foreign missionaries struggled with the Greenlandic language – the one advantage that the official Lutheran Church undoubtedly possessed – Nielsen believed that the Adventists and Pentecostals had the upper hand when it came to worship and media practices. The state Church had become ‘congealed in forms’ and ‘boringly uniform and monotonous’, such that even the singing of hymns was ‘drawn into the boredom’. The new players brought exciting media offerings, substantial aid for the needy, and fresh songs – in other words, ‘the things that speak directly to people’s inner feelings’.

Seeing a tough road ahead for the Lutheran establishment, Nielsen warned that ‘sooner or later’ the labours of the alien proselytes would ‘bear fruit’. He concluded: ‘Whatever one thinks of the work of the foreign missionaries, one cannot ignore the fact that they are doing spiritual revival work.’6

Other Lutheran loyalists in Greenland and Denmark felt let down by the Church’s response to the ‘sects’ flooding into these small coastal communities, believing that it had not equipped the Greenlanders with the intellectual tools and media literacy to ‘clearly distinguish between theological systems’. It had also left them ‘unfamiliar with modern missionary methods’. One Lutheran commentator, Aage Jensen of the Christian Press Bureau in Denmark, urged the Church to undertake more ‘long-term work’ to guide the course of ‘Greenlandic development’ in the brave new world of ecclesiastical pluralism.7

The number of Inuit Greenlanders being baptised was not great – Erik Martinsson baptised six in the 1950s – but the Lutheran Church still felt compelled to respond to the challenge before it became too great, using its press organs to discredit Pentecostalism.8

For the time being, the Pentecostal movement could offer only Swedish- and Danish-language material, including a free tract titled Solstrålen (The Sunbeam) that was advertised in October 1956.9 The caution of the Greenlandic secular government posed another barrier to success, as Åsblom’s plan to open a Pentecostal orphanage in Nanortalik was blocked in 1961 because ‘the authorities [were] concerned … that the children in the home [would] receive a distorted education’. The option of the state taking over ownership of the orphanage ‘at a reasonable price’ was raised, but Åsblom rejected this outright, believing that it was ‘God’s will’ that he ‘should be in Nanortalik’. He is reported to have declared: ‘[H]ere I will stay, even if I have to suffer death for it’. A/G interpreted these words as Åsblom’s way of welcoming ‘martyrdom’.10

Åsblom responded to the media narrative surrounding the orphanage in a letter to the paper, predicting that the hardline approach of the authorities would ultimately backfire because it would raise the suspicions of ‘clear-thinking people’ and ultimately exercise ‘a positive effect on the work of the Pentecostal mission in Greenland’. He promised to forge ahead in whatever way he could, proposing to take in ‘mothers with children’ at the facility instead of orphans. A Danish nurse who was then working in a Salvation Army orphanage in Copenhagen was slated to take charge of the operation.11

Referring in January 1962 to first-hand accounts of his work in Greenland that Åsblom had delivered to Pentecostal meetings across Scandinavia – talks in which he had depicted Greenland as a place blighted by alcoholism and venereal disease – Erik Erngård incredulously told readers of A/G that the missionary was painting himself as ‘one of the most persecuted men in Greenland’; a man bearing constant threats of physical violence and even murder. Through all this, so Erngård said, Åsblom refused to drop plans to open the orphanage despite ‘fierce resistance from the [Lutheran] priests’. These priests were ‘afraid that the children [at the orphanage] will be exposed to a one-sided influence’. Erngård said that Åsblom had made ‘such gross accusations against a particular priest that they cannot be reproduced in print’.

It seems that Åsblom had considered complaining to the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs about his treatment in the Danish territory, though Erngård claimed that this ‘overbearing Pentecostal missionary’ was himself to blame for his misfortunes:

If he left people alone, they would probably leave him alone, but if you want to force cherries on people, you risk getting stones in your eye. We do not sympathise with persecution against people in any form – not even in response to the doomsday harassment to which Mr. Åsblom is exposing the population of Nanortalik – and we sympathise even less with the simplified description of the conditions in Greenland that Mr. Åsblom has felt called to give his fellow believers in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Now he is threatening to go to his country’s foreign ministry. You can rest easy. It will lead neither to a diplomatic break between Denmark and Sweden nor to an urgent case in the [UN] Security Council. At most [it will prompt] a regrettable shrug – and Mr. Åsblom’s misdeeds are not worth more than that.12

Åsblom addressed the various concerns regarding his reports on ‘conditions in Greenland’ to Pentecostal associations in Europe in a lengthy March 1962 article in A/G. In some domains, he noted, the Pentecostal mission was strengthening its position. It had purchased a boat to help missionaries reach the more remote communities of Greenland (though it later sank, which according to Rune nearly killed him and Gunvor). It had also established working relationships with non-Pentecostal abstinence and temperance organisations to tackle the high rates of alcoholism in the country, a problem prevailing not only among adults but also, according to Åsblom’s observations, among children.

In other domains, the Pentecostal movement was struggling to find cultural inroads. Åsblom claimed that the Lutheran establishment had ‘exaggerated a number of things regarding the persecution against us’ and had cast aspersions ‘that could most repulse the people away from us’, allegedly creating an atmosphere in which threats of violence against the missionaries were normalised, spilling over into an actual strike to the head of Åsblom’s colleague Johanne Joelsen. As for his controversial comments about the state of life in Greenland, Åsblom said that he was simply relaying factual information and setting out a case as to why Greenland needed a Pentecostal mission. He also doubled down on his determination to see the orphanage plans through, asserting that ‘the Pentecostal mission is just as good and better at raising Greenland’s children than the folk church itself’.

Whereas Erngård judged that Åsblom’s accusations against a senior Lutheran priest were unsuitable for print, Åsblom himself decided to bring them to the attention of the people of Greenland, purporting in his article to have seen this priest on several occasions ‘drunk on Saturday nights’ and in the company of the alcoholic laity. It was this priest, he said, who was putting up the strongest opposition to the orphanage.

As for the accusation of his being ‘overbearing’ and sectarian, Åsblom declared that he did not ‘want to force people to be saved’. He went on:

[W]e are not a “sect”. My wife and I are members of the Swedish state church, and we demand that the authorities respect that. We are no more sectarian than Marthin Luther himself when he left the Catholic Church. He was the first “sectarian”, and his followers are no better Christians than we who also belong to the Pentecostal movement.13

Further emphasising his ecumenical and Lutheran credentials, Åsblom announced in August 1962 that he and his wife Gunvor were taking responsibility for spreading the cross-denominational tract Tilfredsstillelse, Frihed, Fred (Satisfaction, Freedom, Peace) in Danish and Greenlandic. The tract had already been distributed in Denmark by both the Lutheran and Pentecostal churches.14

In at least one sense, Åsblom was correct: Scandinavian Pentecostalism is best understood not as an entirely separate denomination, but as an ongoing revivalist movement with substantial ties to the Scandinavian Lutheran community, seeking to pull it towards a more pietistic and charismatic form of Christian faith. As Rasmus Bjørgmose noted in A/G in March 1965, ‘several of the communities from Norway and Sweden that are working in Greenland these days come from this revival’.15 Being a realm of the Kingdom of Denmark, Greenland was at the periphery of this Scandinavian Awakening and felt the delayed reverberations of the revolution.

As the decades passed, some Lutherans mocked Åsblom for his apparent lack of progress during his long stay in the country, sneering in particular at his apparently rough Greenlandic language skills. In May 1989, Peter Storch criticised the veteran missionary in A/G with the slightly unfair observation that ‘even though you have been in Greenland for 36 years, you have not learned our language’. Åsblom could speak and write moderately well but had not mastered the intricacies of Greenlandic grammar. Storch also found Åsblom’s views on alcoholism in Greenland to be disingenuous, judging that if he really had ‘wanted to contribute to the elimination of alcohol in Greenland’, he ‘would have had the opportunity to do so’ in three-and-a-half decades.16

However, this dismissiveness occluded the fact that the Pentecostal and ‘Free Church’ movement had gradually become the single most successful new religious phenomenon in Greenland, thoroughly overshadowing its contemporary competitors like the Jehovah’s Witnesses and Seventh-day Adventists.

Though in the early days the independence of the various Free Church establishments had been seen as a limitation, this very same dissipation of leadership responsibilities facilitated fresh initiatives and a diversity of tactics to inject new vitality into the evangelical and Pentecostal scene. By 1990, Pentecostal missions in Maniitsoq, Sisimiut, Aasiaat, Ilulissat, Narsaq and Qaqortoq, all loosely directed by a mission house in Nuuk, reportedly had a combined congregation of around 300 people, and according to Nuuk staff member Elisa Berthelsen these numbers were ‘increasing’.

Conferences bringing the congregations together began in 1985, the 1990 edition taking place in Kangaamiut and featuring sermons by the visiting Jack and Betty Bransford, leaders of the Pentecostal Assemblies of God movement in Alaska. Teaching at the event was conducted in both English and Greenlandic. A/G noted in a report on the conference that young Pentecostal Christians from Sisimiut had also begun to stage public dramas to spread the gospel, executing one such performance in front of the Kangaamiut market.17

Greenland’s evangelical movement was given another shot in the arm in 1996 when JESUS, a 1979 film distributed by the Jesus Film Project of the international non-denominational Christian campaign Campus Crusade for Christ, was translated into Greenlandic and became available for showings in Greenlandic churches. Readers of the evangelical magazine Mission Herald were told that this was ‘the first feature film to be translated into the Greenlandic language’. Errol Martens, director of the film’s Greenlandic translation, said that the national television station in Nuuk wished to broadcast the film, and he called on churches to ‘send teams out all over Greenland’ with it.18

New Life (2000-present)

In the year 2000, congregations belonging to the Apostolic Church, Missionary Union, and Swedish Pentecostal Church in Greenland banded together to form a new association called New Life Church/Inuunerup Nutaap Oqaluffia (INO), also known in Danish as Grønlands Frikirke (Free Church of Greenland). According to the statutes and statement of faith adopted in 2004, INO members ‘confess to the Christian faith as it is expressed in the Apostles’ Creed’, including a Trinitarian view of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; a belief in the ‘absolute depravity of human nature [and] the necessity of repentance and regeneration by faith in Jesus Christ as the Son of God’; use of the ‘gifts of the Holy Spirit’; and the anticipation of Christ’s ‘return and millennial reign on earth’. INO’s overall purpose is to ‘fulfil the missionary mandate by preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ, making disciples, and working for the Christian unity in accordance with the New Testament’, and the group set a specific target for the conversion of at least 10% of Greenlanders.19

INO gained recognition from the Danish Ministry of Church Affairs in 2003, and was among the 138 religious organisations officially recognised by Denmark as of 2006, giving it, among other things, the right to conduct marriages.20 It had a total membership of 500 by 2009, shared out between Nuuk, Maniitsoq, Sisimiut, Aasiaat, Qasigiannguit, Ilulissat, Uummannaq, Upernavik and Qaanaaq.21 Rune Åsblom, then in his eighties, continued to visit Greenland to participate in the life of the church until well into the 2010s, starting a business and working to build a mission house in Qasigiannguit,22 and his children have carried on his legacy in collaboration with the Swedish Trosgnistan’s Mission organisation from their base at the Zion mission house in Sisimiut.23 However, de facto leadership had passed to John Østergaard Nielsen, head pastor of INO Nuuk.

Østergaard Nielsen, his wife Ulla, and their two daughters arrived in Nuuk in 1987 with support from the Apostolic Church in Denmark, joining a small existing Apostolic congregation of five Danes and two Inuit Greenlanders. John worked as a teacher, while Ulla worked as a nurse at Queen Ingrid’s Hospital. The family returned to Denmark for a few years after the birth of their third daughter, but John served his small Greenland flock as a commuting pastor until, in 1992, they moved permanently to Nuuk. John and Ulla became part of the council of elders of INO when the organisation was founded in 2000, John being head pastor of INO in Nuuk. A series of sermons by the visiting Danish preacher Hans Berntsen in the early 2000s greatly increased the public notoriety of the church, drawing hundreds – supposedly as many as 500 – to each event.

Under the leadership of the elders, among whom Østergaard Nielsen was the most prominent, INO tried to maintain friendly relations with the Lutheran Church and participated in joint ceremonies on occasions like International Women’s Day of Prayer, but in some areas of theology and social politics INO was markedly more conservative than the Lutheran clergy or laity. While Østergaard Nielsen insists that INO ‘is not homophobic and wants to be open’, he states plainly that the organisation cannot ‘override’ the perceived biblical proscription of same-sex relationships and marriages. This was a red line for INO. The church leadership was willing to go so far as to ‘renounce the right to marry, if or when it is legislated that homosexuals must be able to marry regardless of religion’, in order to remain faithful to its views on homosexuality. (Greenland legalised same-sex marriage in 2016 but INO is not obligated to conduct same-sex unions.)

Since 2009, INO’s greatest cultural tool has been Inuunerup Nipaa (Voice of Life), a radio channel broadcasting Christian news and music from a dedicated studio in Nuuk every morning, afternoon, and evening. One INO member, Augustine Christensen, has recorded a full Greenlandic-language Bible audiobook which the church distributes for free. In 2018, Østergaard Nielsen handed over leadership of INO in Nuuk to 31-year-old Appaleq Petersen.24 There were thirteen INO branches as of October 2024.25

According to a 2010 profile of the INO Nuuk church by Stig Öberg, its 100-person congregation, which by then accounted for 0.5% of the population of the city, enjoyed its most rapid period of growth in the early 2000s off the back of the sermons by Berntsen, the JESUS film (selling 3,000 copies), and a new wave of on-the-ground work by INO representatives in Greenland’s many small villages. In 2004, twelve INO leaders travelled to Iqaluit in Nunavut, Canada to participate in a joint conference with other Arctic and sub-Arctic Christian groups – an event during which Østergaard Nielsen reports that a strange golden substance or ‘manna’ descended on the attendees. The INO Nuuk congregation supposedly then experienced similar occurrences on his return, sparking waves of emotional eruptions as congregants believed they were encountering the Holy Spirit. Østergaard Nielsen told Öberg: ‘Something followed us home.’

International ties were also strengthened by visits from American Christian groups like the Celebrant Singers and correspondence with other groups like the Assemblies of God. Inuit INO members received education and leadership training from the Scandinavian Free Church Commission. Elisa and Aqqalu Berthelsen were among the first Inuit Greenlanders to take up leadership roles, becoming elders in INO shortly after its formation.26

INO worship meetings follow the same general format that one finds in many Pentecostal and charismatic evangelical church all around the world. There is a firm emphasis on the reality, efficacy, and use of spiritual gifts, including healing (often accompanied by the laying on of hands) and tongues (in Pentecostal and charismatic contexts, this usually refers to members speaking out in words and syntaxes that do not correspond to any ‘real’ language, followed by an ‘interpretation’ in the vernacular language by another member). INO meetings often involve ‘a lot of joy and jubilation, but also sometimes heartbreaking crying’.27

Öberg relates that the confidence of Pentecostal and evangelical converts in Greenland has dramatically improved since the early decades of missionary work. Whereas converts in prior decades would more often than not drift out of the community due in part to the ‘odious’ social reputation attached to leaving the Lutheran Church to join one of the new religious groups, in the twenty-first century, Öberg claims, a conversion ‘tends to become more permanent’, with the result that ‘congregations grow numerically’.28

The spirit of success

Explaining the relative success of Pentecostalism in Greenland is a complicated matter. One factor is the numerical abundance of its missionaries and the fact that, from the very beginning, they were spread out across the island. Many of these missionaries did not stay for long, but their presence gave Pentecostalism a broader reach than was achieved by the comparatively tiny cohorts sent by other groups. Moreover, Pentecostalism can function fairly well alongside other charismatic evangelical traditions, meaning that it can form coalitions like INO, whereas other groups like Seventh-day Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses are doctrinally exclusive and not widely accepted by other Christians.

Another factor is found in the very nature of Pentecostal belief. Anthropologists Frédéric Laugrand and Jarich Oosten argue that the popularity of Pentecostal, charismatic, and evangelical movements in Greenland owes partly to the ways in which their practices of spiritual healing, speaking in tongues, and exorcism for demonic possession resemble and give legitimised expression to Inuit shamanic traditions that were long suppressed by the Folk Church.29 Pentecostalism is therefore a syncretic space in which Christian meta-doctrine – monotheism, sin, atonement through Christ, etc – can be combined with shamanic ritual. This is precisely the reason that Chris Shull, a Baptist missionary who has led a church in Ilulissat since 2007, expressly discourages Pentecostal styles of worship in his congregation, believing that they are too reminiscent of a pantheistic and animistic urge that still ‘lurks in the culture’.30

Öberg asked several people about INO’s success around the time of his visit to Nuuk in 2009. Oluf Schönbeck, a scholar of religion from Copenhagen who interviewed many INO members, emphasises the communal aspect and observes that INO ‘does not make you feel like a stranger in the church’. Meanwhile, Danish-Greenlandic Lutheran priest Aviaja Rohmann Pedersen argues that, in addition to the strong sense of community that it offers, INO stands out by emphasising personal faith and one’s relationship with God rather than rigid formalism and impersonal liturgy. Energetic worship, modern music, spiritual healing, and speaking in tongues all give congregants a sensation that they are part of something unique that the Lutheran Church cannot emulate. In Öberg’s own survey of INO members, 79% listed ‘feeling the presence of God’ among their main reasons for attending.31

Interest in these things is not a uniquely Inuit feature, so while surface-level commonalities between charismatic or Pentecostal worship and Inuit shamanism are interesting and may be contributing factors, they should not be seen as the reason for INO’s growth.

Notes

- ‘Rune Åsblom 91 år’, Soderhamns Kuriren, 13 April 2016. https://www.soderhamnskuriren.se/2016-04-13/rune-asblom-91-ar ↩︎

- ‘Halva livet på ett isigt Grönland’, Dagen, 19 November 2003. https://www.dagen.se/familj/2003/11/19/halva-livet-pa-ett-isigt-gronland/ ↩︎

- S. Öberg, Pingst i Grönland: En studie av den grönländska frikyrkan, Inuunerup Nutaap Oqaluffia (Uppsala: Institutet för Pentekostala Studier, 2010), p. 12. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 23. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 13-18. ↩︎

- F. Nielsen, ‘Kampen om sjælene’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 95, no. 4, 24 February 1955, p. 21. https://timarit.is/page/3777796 ↩︎

- ‘Vil folkekirken kende sit ansvar?’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 98, no. 8, 24 April 1958, p. 17. https://timarit.is/page/3779815 ↩︎

- E. Martinsson, ‘Frikyrklighetens födslovånda på Grönland’, Evangelii Härold, vol. 29, 1958, pp. 6-7. ↩︎

- R. Åsblom, ‘atuagagssak akekángitsumik!’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 96, no. 20, 18 October 1956, p. 25. https://timarit.is/page/3778796 ↩︎

- ‘Martyrdøden’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 101, no. 23, 2 November 1961, p. 18. https://timarit.is/page/3782559 ↩︎

- R. Åsblom, ‘Svar på artikeln »Martyrdøden«’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 1, 4 January 1962, p. 10. https://timarit.is/page/3782678 ↩︎

- E. Erngård, ‘En forfulgt pinsemissionær’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 1, 4 January 1962, p. 11. https://timarit.is/page/3782678 ↩︎

- R. Åsblom, ‘Pinsemissionen endnu engang’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 6, 15 March 1962, p. 10. https://timarit.is/page/3782826 ↩︎

- ‘Tilfredsstillelse, frihed, fred’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 17, 16 August 1962, p. 13. https://timarit.is/page/3783149 ↩︎

- R. Bjørgmose, ‘Den kirkelige strid i Danmark’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 105, no. 5, 4 March 1965, p. 6. https://timarit.is/page/3785213 ↩︎

- P. Storch, ‘»Palasiusaamut« Rune Åsblom-imut akissut’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 129, no. 51, 10 May 1989, p. 15. https://timarit.is/page/3822905 ↩︎

- ‘Kristumiut aasarsiortut’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 130, no. 96, 22 August 1990, p. 16. https://timarit.is/page/3826665 ↩︎

- ‘Greenland “Jesus” film makes history’, Mission Herald, September/October 1998, p. 6. https://archive.org/details/missionary-herald-1998/page/6 ↩︎

- Öberg, Pingst i Grönland, pp. 20-2. ↩︎

- ‘Frikirke godkendt’, Sermitsiaq, 26 February 2008. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/frikirke-godkendt/548399 ↩︎

- ‘Grønlands frikirke i Sverige’, Sermitsiaq, 24 May 2009. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/gronlands-frikirke-i-sverige/547600 ↩︎

- ‘Halva livet på ett isigt Grönland’, Dagen. ↩︎

- Trosgnistan’s Mission, ‘Med evangelium till Grönland’, 2020. https://www.trosgnistan.se/gronlandsmissionen ↩︎

- I. S. Rasmussen, ‘Chefredaktøren anbefaler: Mit gode liv i Nuuk’, Sermitsiaq, 24 August 2018. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/chefredaktoren-anbefaler-mit-gode-liv-i-nuuk/576748 ↩︎

- ‘Kontakt kirken’, Inuunerup Nutaap Oqaluffia website. https://ino.gl/en/contactus ↩︎

- Öberg, Pingst i Grönland, pp. 26-33. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 34. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 37. ↩︎

- F. B. Laugrand and J. G. Oosten, Inuit shamanism and Christianity: Transitions and transformations in the twentieth century (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010), pp. 342-71. ↩︎

- J. Duin, ‘The pastor at the top of the world’, Newsweek, 20 October 2021. https://www.newsweek.com/pastor-top-world-1640942 ↩︎

- Öberg, Pingst i Grönland, pp. 38-46. ↩︎

2 responses to “Pentecostalism in Greenland”

[…] the Jehovah’s Witnesses seemed to ask for a renewed urgency in Lutheran pastoral activities. The Pentecostal missionary Rune Åsblom urged the priests of the established Church: ‘We need to help people stop […]

LikeLike

[…] strips to aid his evangelism — a much-needed spice in an area now also being worked by energetic Pentecostal missionaries.63 A slide projector and a fur coat were gifted him by Adventists in […]

LikeLike