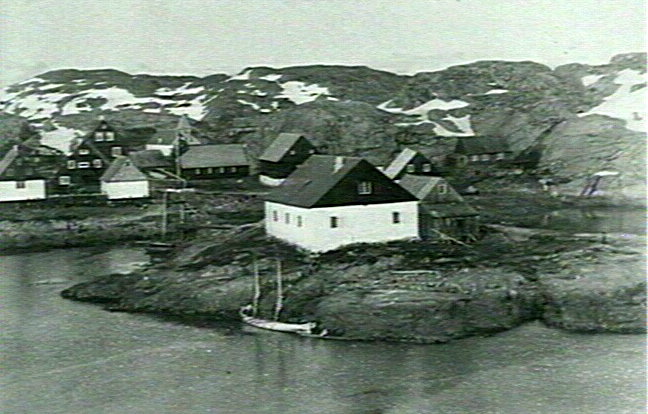

The first Local Spiritual Assembly in Nuuk. A/G, 7 June 1979.

- ‘A modest beginning’ (1910-1950)

- Pioneers and converts (1950-1970)

- Building a community (1970-1992)

- ‘Dogged perseverance’ (1992-2024)

- Notes

Beyond traditional Inuit shamanism and Christianity (including ‘sects’ like the Jehovah’s Witnesses), the oldest and largest religion in Greenland is the Bahá’í Faith, which was first brought to the island through a literature propagation campaign in 1946. The first Bahá’í to live in Greenland arrived in 1951, and there are now around 150 believers,1 making the faith significantly larger than its close relative, Islam.

The Bahá’í Faith is a monotheistic, messianic, quasi-Abrahamic tradition founded in Iran during the late nineteenth century. It has its roots in Bábism, another movement formed earlier in the nineteenth century by a figure known as the Báb, and it takes many of its structural and stylistic cues from Islam, although it has generally been proscribed by Islamic authorities due to its belief in continuing revelation (i.e., prophetic revelation after the Prophet Muhammad) and its opposition to hierarchical religious power structures.2

The core scriptural text of the religion is the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, composed by the founding figure Baháʼu’lláh in 1873,3 but Bahá’í leaders also commonly cite the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, the Qu’ran, and the Hadith as part of a continuous chain of prophetic revelation. A key principle in the faith is that of unity – or the ‘oneness’ of God, of humanity, and of religions. This manifests in Bahá’í practice as a drive to translate the spiritual equality of all people into a social (and political) reality on Earth, transcending gender, race, faith, and class. Bahá’í leadership is based on elections, from local organisations to the highest authority of the faith, the Universal House of Justice. There are today around 7-8 million Bahá’ís spread out across nearly every country.4

‘A modest beginning’ (1910-1950)

Like many Christians (e.g., the Seventh-day Adventists), some Bahá’ís in the early twentieth century found themselves drawn to Greenland by Reginald Heber’s popular hymn ‘From Greenland’s Icy Mountains’, the first verse of which became something of a gold standard for evangelistic groups with ambitions to go global: ‘From Greenland’s icy mountains, to India’s coral strand / Where Afric’s sunny fountains roll down their golden sand / From many an ancient river, from many a palmy plain / They call us to deliver their land from error’s chain.’ Bahá’í writers were using this hymn as a reference point for their own ambitions for worldwide reach as early as 1910.5

However, the desire of the Bahá’ís to reach Greenland stemmed more from the writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the faith’s second leader – and particularly the Tablets of the Divine Plan, a series of letters to the Bahá’í communities of North America penned between 1916 and 1917. The fifth tablet, comprising a revelation to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on 15 April 1916 and presented as a letter ‘to the Bahá’ís of Canada and Greenland’, called for religious action in the far north:

Perchance, God willing, the call of the Kingdom may reach the ears of the Eskimos, the inhabitants of the Islands of Franklin in the north of Canada, as well as Greenland. Should in Greenland the fire of the love of God be ignited, all the ices of that continent will be melted and its frigid climate will be changed into a temperate climate – that is, if the hearts will obtain the heat of the love of God, that country and continent will become a divine garden and a lordly orchard, and the souls, like unto the fruitful trees, will obtain the utmost freshness and delicacy. Magnanimity is necessary, heavenly exertion is called for. Should you display an effort, so that the fragrances of God be diffused amongst the Eskimos, its effect will be very great and far-reaching. … The continent and the islands of Eskimos are also parts of this earth. They must similarly receive a portion of the bestowals of the most great guidance.6

In the thirteenth tablet, dated 21 February 1917, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá instructed Canadian Bahá’ís: ‘dispatch ye teachers to Greenland and the home of the Eskimos’.7 Encouraged by these prophetic injunctions, Bahá’í believers in North America began looking for opportunities to fulfil the task. In September 1916, Ella G. Cooper, a member of the Executive Board of Bahá’í Temple Unity in the United States, wrote to the president of the Board, suggesting that an exploratory trip by one Susan Rice to Alaska and Yukon ‘may prove to be a beginning which will eventually lead to our reaching the Eskimos [of Canada] … and perhaps even to Greenland’.8 In October 1916, a Teaching Campaign was organised to carry out ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s instructions for a new wave of evangelism, with responsibility for Greenland being assigned to the Northern Territory headquartered in Montréal.9

This Campaign never reached Greenland. If any formal investigation was undertaken, it would have discovered that Greenland was subject to a Lutheran ecclesiastical monopoly (only abolished in 1953) and was not open to foreign missions.10 Though they were cognisant of the fact that they had yet to execute their duties in the region,11 Bahá’ís could only exercise their interest in Greenland at a distance through mentions of Greenlandic history and anthropology in their periodicals.12 In July 1940, for instance, the North American Bahá’í Race Unity Committee published an article guiding readers through the nature of ‘Eskimo’ life in Greenland, including their manner of fishing, their dwellings, their family and social structures, and their musical traditions. Overall, the article described Inuit living conditions as ‘very simple’.13

In 1946, a Danish Bahá’í woman named Johanne Sorensen (later Johanne Høeg) took the first substantial step in the propagation of the Faith in Greenland, sending, according to her official obituary, ‘literature and a picture of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to all radio stations and outstations’ on the island.14 One of the settlements to receive literature was Upernavik, inside the Arctic Circle,15 the hometown of an Inuit man named Hendrik Olsen who would later become the first Greenlandic convert. Sorensen continued her distribution campaign over the coming years, and by the close of the 1940s she had sent literature to 48 settlements, including Thule/Qaanaaq and Etah (a now-abandoned village) at the northern tip of the country.16

Shoghi Effendi, grandson of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Guardian of the Bahá’í Faith (de facto leader) from 1921 to 1957, described Sorensen’s work as ‘a modest yet historic beginning which the Canadian believers, in the light of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Tablets addressed to them, must follow up in the years to come’.17 Under Effendi’s leadership the prospect of a manned mission to Greenland was inching closer to reality. On 5 June 1947, he tasked the Canadian Bahá’ís with bringing the message ‘to Newfoundland, [the] Franklin Islands, Yukon, Mackenzie Keewateen, Ungava, [and] Greenland’.18 In a cabled message to the April 1948 Canadian Bahá’í Convention he again urged ‘the formation of a nucleus of the Faith in the Territory of Greenland’, noting that this place had been ‘singled out for special mention by the Author of the Divine Plan’.19 In response, the Canadian National Spiritual Assembly (NSA) set up ‘a special teaching committee for Greenland and Newfoundland’.20

Reflecting on the challenges facing the Bahá’í community in the fall of 1949, Effendi wrote:

The magnitude of the tasks these heroes and champions of the Faith are summoned, at this hour, crowded with destiny, to discharge from the borders of Greenland to the southern extremity of Chile in the western Hemisphere, and from Scandinavia in the North, to the Iberian peninsula in the south of the European continent, is, indeed, breath-taking in its implications and back-breaking in the strain it imposes.21

New Southgate Cemetery in London. Wikimedia Commons.

Pioneers and converts (1950-1970)

The 1950s began with great promise. Guardian Effendi announced in April 1950 that Bahá’í literature had now been translated into ‘Eskimo’ (i.e., Inuktitut, the tongue of the Inuit in Nunavut, Canada, and a close relative of Kalaallisut/West Greenlandic).22 Around the same time, an American Pioneer (missionary) and violinist named Nancy Gates was said to be ‘en route from Denmark to Greenland to pioneer’ under the auspices of the Canadian NSA,23 discussions to this end having taken place between Effendi and the national and continental committees of Denmark, Europe, and Canada.24 With Greenland still being closed to outside religious influences, Gates’s journey was never likely to succeed. A collection of Effendi’s writings to the Canadian Bahá’ís, published in 1965, notes simply that she ‘attempted to pioneer to Greenland, but was unable to do so’.25

Sending a pioneer, especially a non-Danish pioneer, whose sole purpose was to proselytise in Greenland was always going to be a hard thing to sell to the Danish authorities, but the Greenland Committee of the Canadian Bahá’ís found a workaround that allowed them to establish a presence before the 1953 Danish Constitution abolished the Lutheran ecclesiastical monopoly. The solution was to have a Danish Bahá’í individual undertake secular work on the island.

In June 1951, Canadian Bahá’í News announced that ‘the great difficulty of finding a pioneer for Greenland has been resolved’, as Palle Bischoff, a 26-year-old Danish commercial science graduate who had only converted to the Bahá’í Faith four years previously, was appointed by the Danish authorities to be manager of a fishing station in Egedesminde/Aasiaat, where he was to live four months out of the year while serving as manager of the ‘Govkussak’ fishery in the winter months. Bischoff in fact spent most of his time in Greenland in Sukkertoppen/Maniitsoq, and the mention of Aasiaat could be a case of mistaken geography. Either way, his arrival was an historic moment.

In a statement to the Greenland Committee of the Canadian NSA, Bischoff said: ‘It is exciting and I pray that I will be able to light the fire of the love of God among the people there so that the unity and harmony of the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh will be manifested also in that country.’26

Bischoff arrived in Greenland later in 1951. He wrote of his journey:

The evening before we were due to see the first of Greenland I went out in the still night in the front of the ship and said the Greatest Name [i.e., ‘Bahá’, or Glorious, a name for God] 95 times. I prayed that both in this country and the rest of the world people would turn their hearts to the Spring of Life; that Bahá’ís throughout the countries, deeper and deeper, would understand the greatness of the message of Bahá’u’lláh and make His Teaching to be their lives.

Dagmar Dole of the Copenhagen NSA noted that the young man was ‘approaching a very difficult job, in a material as well as a spiritual sense, and will need all of the prayers he can get. He has asked for them.’ In its reporting, Bahá’í News recalled the prophecy of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá that ‘all the ices of that continent will be melted’ should ‘the fire of the love of God be ignited’ there.27 Effendi, meanwhile, was pleased to hear that ‘the opening stage of the campaign to carry the Faith to the Eskimos’ had finally been taken, and exhorted the Canadian NSA to ensure that this work did not ‘suffer any setback’.28

Ever enamoured with the far north, Effendi went on to communicate via the hand of his wife Rúhíyyih Khánum Rabbani his pleasure with the ‘exemplary’ work being done among the Inuit of Greenland and Canada, stating that these pioneers were ‘rendering a far greater service than they, themselves, are aware of, the fruits of which will be seen … in other countries where primitive populations must be taught’. Any Bahá’í who took on the challenge of pioneering in Greenland would carry the hefty responsibility of making a positive first impression as ‘a guest of people in a different climate and environment, of a different nationality and speaking a different language’. The same address, dated June 1952, noted that there had recently been an ‘opening for a Canadian believer to visit the Governor of Greenland and his wife’.29 The Canadian believer in question is probably John Robarts, who, seeking a way around the ‘complicated’ permission process for travelling to Greenland, ‘met with officials for Greenland and won goodwill and the promise of cooperation’.30 This occurred in 1949.31

The adoption of a new Danish Constitution in 1953, which brought with it the abolition of Greenland’s colonial status and, by extension, the Lutheran ecclesiastical monopoly, was a key turning point for many religious groups seeking to enter Greenland, including Jehovah’s Witnesses and Catholics. But for the Bahá’ís, who had already made some progress through the remote distribution of literature and through the residence of a Bahá’í believer on secular business, 1953 passed without much consequence, although the presence of Bischoff enabled Bahá’ís elsewhere to boast of the geographical reach of their religion.32

Effendi again called for consolidation in the northern regions in April 1953,33 and in June 1954 he told Canadian Bahá’ís: ‘Particular attention should be directed to Iceland and Greenland, as the two foremost objectives of this community in connection with the work of consolidation assigned to its members.’34 Similar messages from the Guardian came in 1956, with one letter calling upon the Canadians to seek ‘the enhancement of the prestige it has deservedly won in recent years throughout the Bahá’í World’ via its northern campaigns.35

Bischoff, for his part, continued working in Maniitsoq until he returned to Denmark in 1954.36 Another Bahá’í, a Canadian man named William Carr, arrived in 1955 at Thule Air Base in northern Greenland on US Air Force business, becoming the northernmost practitioner of the religion at this time.37 Effendi made special note of Carr’s work, writing that he, as a ‘lone pioneer’, was ‘demonstrating the Bahá’í spirit in such an exemplary manner’.38 Bahá’í News suggested in December 1955 that there was at that time only one Bahá’í on the island,39 but a note in the 1965 edition of Effendi’s Messages to Canada states that a Danish woman, Kaya Holck, also ‘pioneered among the Greenlanders’ from 1955 to 1963.40

Another slight contemporary misapprehension concerns the timing of the first Greenlandic convert. The Bahá’í World, a series of compendia collating significant events and developments in the history of the faith, states in the volume covering the years 1950-1954 that the ‘first Greenlandic’ convert had been ‘enrolled’ in April 1954.41 This chronology is technically erroneous, but it is most likely referring to Hendrik Olsen, an Inuit Greenlander who began communicating via letter with Johanne Sorensen/Høeg in 1946 after encountering some of the literature she had sent.

Olsen was a well-known figure in Greenlandic public life, having served as an elected politician and as a Kalaallisut translator for various works, including some of Knud Rasmussen’s books. His Bahá’í obituary, which describes him as ‘a direct descendant of the first Greenlandic Christian’ (possibly meaning Papa, or Frederik Christian, who converted and was baptised in 1724), states that he ‘began serving the Cause many years before he became formally affiliated with it’, one significant contribution being the translation of some of Bahá’u’lláh’s works into Kalaallisut, a feat he achieved with the assistance of a Lutheran priest. In the spring of 1965, Olsen wrote to Høeg, now a member of the Auxiliary Board of the Danish Bahá’ís, telling her that he wished to meet in person.42

That summer, Høeg and her colleague, Dr. Hooshang Ra’fat, travelled to Greenland by plane and boat, and at a meeting in Olsen’s home, with Høeg and Ra’fat as witnesses, he signed his acceptance of the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, ‘expressing regret for not having done so much earlier’.43 To demonstrate the depth of his faith he offered to complete the translation of John Esslemont’s Bahá’u’lláh and the New Era (1923) into Kalaallisut.44 Bahá’í News reported that the trip to Greenland ‘resulted in much excellent publicity for the Faith’, stating that in Upernavik, Olsen’s hometown, a public meeting was attended by 100 people.45 Olsen passed away just two years later, on 20 June 1967.

The next stage of Bahá’í expansion began in April 1966 when Lotus and John Nielsen, both members of the National Spiritual Assembly of Sweden, departed for Greenland. John was attracted to the island because of his Danish background, while Lotus ‘liked the idea of an unfulfilled goal’. At that time, William Carr was still living at Thule Air Base and Hendrik Olsen was living in Holsteinsborg/Sisimiut, so the Nielsens and their children headed for Godthåb/Nuuk, the country’s capital city, which had been a target destination for some years. Moving into a small house in the city, John worked as a taxi and truck driver and the couple soon launched a small newspaper, while in 1967 they opened a furniture store and sold, among other things, Persian rugs imported from Iran by an Iranian Bahá’í living in Copenhagen.

Due in large part to the dominance of the Lutheran Church in Greenland, Lotus’s obituary notes, ‘introducing a new religion turned out to be quite difficult’, but over time a series of Bahá’ís from Denmark and North America visited to break their spiritual loneliness, and in 1970 the Nielsens could celebrate their first convert, a Danish nurse named Else Boesen. This small victory signalled the beginning of a period of sustained growth for the Bahá’í community in Greenland.46

Building a community (1970-1992)

As delegates from Europe and North America descended upon Reykjavik, Iceland, for the North Atlantic Oceanic Conference in September 1971, the accelerated propagation of the Bahá’í Faith in Greenland occupied the minds of many, not least that of the Canadian John Robarts, who was among the final batch of believers to be elevated to the prestigious position of Hand of the Cause of God, the topmost rank in the religion, in 1957. Robarts bore responsibility for communicating a special message from the Universal House of Justice, the Bahá’í governing body, to the effect that the mission to Greenland was now to be regarded as an immediate priority, while Jameson Bond, a Knight of Bahá’u’lláh, delivered a talk on the history of Bahá’í activity among the Greenlanders.

Moved by the weight of the occasion, a group of five, including ‘a Danish believer [Lotus Nielsen], two Canadian Indian believers [of the Blackfoot Confederacy], a French-Canadian believer and an Eskimo [Florence Springay]’, boarded a plane on Sunday, 5 September, the last day of the conference, for a day trip to the previously-unvisited village of Kulusuk in East Greenland, spending three hours there before heading back to Iceland. A report from the event paints an effusive picture:

They were able to teach the Faith openly to villagers and community leaders, and established bonds of friendship which left all involved in tears when the delegation boarded its plane to return to the Conference, its arrival coinciding with a special teaching meeting where they were enabled to give the friends an account of their moving experiences.47

Another report added further details of emotional character:

They received a warm and loving reception from the Eskimos. One Eskimo lady, after receiving a picture of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, clasped it to her breast, rocked it like a baby, and wept tears of joy. … As the Canadian Charter flight headed back toward Canada, the plane flew across Greenland. One could see the glaciers flowing into the sea and the huge icebergs floating along the inhospitable coastline. As 250 Bahá’ís recited the Greatest Name, one could not but feel that the melting process was being hastened!

Following the injunctions of the Universal House of Justice, an Auxiliary Board member from Canada named Peggy Ross ‘left on a teaching trip to Greenland at the end of the Conference’.48

Back in Nuuk, the marriage of Lotus and John Nielsen was deteriorating, eventually leading to their divorce in 1975. With John fading from the picture, Lotus, still having to balance her family, work, and religious responsibilities, sold the furniture store and instead opened a small gift shop, naming it the Arctic Gallery. Each year, she closed the shop on Naw-Rúz, a Bahá’í holy day and the first day of the Bahá’í calendar.49 Fortunately for Lotus, Greenland was beginning to attract much more sustained interest from the global Bahá’í community, particularly from the Canadian and Danish governing bodies. A conference on spreading the faith in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions held at Tórshavn in the Faroe Islands in August 1974 ensured that the momentum would not be lost.50 Expansion would no longer be the preserve of individual initiative.

On 13 September 1974, with financial assistance from the Canadian Bahá’ís, the small Bahá’í community in Nuuk concluded negotiations with the Danish authorities to purchase a modest two-story wooden building which was to be converted into the group’s Ḥaẓíratu’l-Quds – a centre of religious life comparable to a church or mosque. In welcoming the purchase, the Danish NSA noted in particular ‘the increased facility for teaching and consolidation that it affords’.51

Meanwhile, the Bahá’ís were rapidly increasing their visibility and reach on the island. In 1975, when Hand of the Cause Bill Sears briefly landed in Greenland during a refuelling stop on his way to Iceland, he was ‘greeted by a colorful Bahá’í poster on the wall of the air terminal’.52 Under the direction of Peggy Ross, Lotus Nielsen undertook a teaching trip to Maniitsoq that same year, bringing projector slides to communicate the Bahá’í message to a whole new audience. Only one man – the one who had drawn up a poster advertising the event – attended the meeting, but he agreed to translate Nielsen’s words into Kalaallisut for the benefit of his neighbours. Moving on to Sisimiut, Nielsen distributed literature at people’s doorsteps and in public spaces, and also visited the widow of Hendrik Olsen.53

The Greenlandic Bahá’í community was also beginning to reach out onto the world stage by sending its own representatives to Bahá’í conferences.54 Representatives from Greenland were present at the First North American Bahá’í Native Council in 1978, for instance,55 and an Inuit Greenlander named Jens Lyberth spoke at the second edition of the Council in July 1980.56 Another Inuit Greenlander who had married a Swedish Bahá’í attended the 1979-80 Winter School in Sweden, where she ‘declared her belief in Bahá’u’lláh’.57

One core piece was still missing: a Local Spiritual Assembly, i.e., the organisational structure one step below a National Spiritual Assembly. This lingering absence was noted at the International Teaching Conference in Helsinki, Finland, in July 1976.58 On 17 April 1979, nearly thirty years after the first Bahá’í arrived in Greenland, the Nuuk Local Spiritual Assembly was formed, consisting of a mix of Scandinavian and Inuit believers.59

It was at this point that the Greenlandic press, particularly the bilingual newspaper Atuagagdliutit / Grønlandsposten (A/G), began to pay attention to the growth of the Bahá’í community in their midst. A/G interviewed a Danish Bahá’í who was in the country for the launch of the Assembly, asking him questions about the basics of Bahá’í belief and practice.60 A few weeks later, on 26 July 1979, Greenland’s Bahá’ís placed a Danish-language advertisement for their faith in A/G:

Bahá’í is not only a religion but also a guide for life. In the Bahá’í faith, we can find true spiritual principles that are also found in many other faiths. These true principles, however, are now expressed in the Bahá’í scriptures in accordance with the requirements of the age in which we live.61

Another advertisement placed in February 1980 said that at the core of the Bahá’í philosophy is a belief in ‘the unity of humanity – cooperation among all peoples, races, nations, classes and religions in the spirit of understanding, united in their purpose under the guidance of the one God in whom all believe’.62

These promotional pieces coincided with a renewed effort to consolidate the existing community and reach out into Greenlandic society. Nine Bahá’ís participated in the Nuuk Spiritual Assembly’s first summer school, held in Qaqortoq in July 1980 at the instigation of Erik Nielsen, a pioneer who had been living there since 1977. They were joined at three public meetings by 12 ‘seekers’, i.e., non-Bahá’í who wished to learn about the religion.63 In October 1981 a contingent of Alaskan believers came to Greenland to aid in teaching activities there,64 and in the summer of 1982 Erik Nielsen in Qaqortoq was visited by Gol Aidun, a travelling Canadian teacher, who spoke at local schools and a women’s organisation.65 Around the same time Lise Quistgaard Raben, secretary of the Danish NSA, visited Sisimiut, Nuuk, and Qaqortoq on a four-week teaching expedition, meeting in the process the mayor of Qaqortoq and the municipal director of Nuuk and handing to the latter a Danish copy of Bahá’u’lláh and the New Era.66

Rúhíyyih Khánum Rabbani, the widow of Shoghi Effendi and herself a Hand of the Cause, visited Greenland in September 1982 as part of her North American tour. An invitation to her lecture on 16 September was placed in A/G, where it was explained that while the Bahá’ís have ‘neither priests nor popes’, believers regarded her in a manner not so dissimilar to ‘the feelings of Catholics for their pope’. Speakers of English, Danish, and Kalaallisut would all be accommodated, and those who wanted more could attend the follow-up event with Rabbani on 18 September marking the inauguration of the Bahá’í facility in Nuuk.67 The edition of The Bahá’í World covering the years 1979-1983 notes that Rabbani met with ‘many high officials including … the Eskimo Premier and Danish Governor of Greenland’, and claims that eleven ‘young Greenlanders’ converted to the faith shortly afterwards.68

Rabbani’s visit was followed up in November 1982 by Shirley Lindstrom, a Bahá’í woman of the Tlingit peoples of Alaska. Lindstrom’s presence attracted the curiosity of A/G, and she was asked to explain many aspects of the Bahá’í Faith for the uninitiated. It is in this article that A/G first quoted the prophecy of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá concerning the melting of Greenland’s ice should the inhabitants be converted. The paper also revealed that by this time there were 17 Bahá’ís resident in Greenland.69

Though Christian purists rejected Bahá’ísm outright because it ‘changed the foundations’ of Christian belief,70 the universalism of the religion proved quite popular with some young Greenlanders, including one Nuka Møller, who converted in 1982 while studying in his early-20s. Møller explained: ‘My reason for becoming a Bahá’í is that I believe in Baháʼu’lláh, the founder of the Bahai Faith, as the messenger of God in our day. I also believe that his teachings are correct.’ He was particularly impressed by the belief that ‘all religions are equal’, and by the commitment of the Bahá’ís to the ‘unity of different peoples’ regardless of race, sex, and religion.71 The Local Spiritual Assembly ensured that these progressive beliefs were publicised through A/G placements, such as one timed to correspond with International Women’s Day in 1988 which declared that the Bahá’ís worked ‘for a world where there is equality between the two sexes’.72 The theme of the Summer School course in 1988 was ‘Peace and Unity’.73 Meanwhile, educational activities designed for children ensured a continued presence among younger generations of Greenlanders.74

Another reason the faith was attractive to young people was its heavy interest and involvement in the arts. A pair of young artists named Hilde and Kaka became the first Greenlandic couple to be married in the Bahá’í religion and the first couple married by the Nuuk Spiritual Assembly in September 1984.75 Later, in September 1988, a play ‘based on Bahá’í principles as they relate to family and human relationships’ was performed at a Nuuk arts festival.76

The 1980s also saw a gradual increase in the availability of Bahá’í literature in Kalaallisut. When Hendrik Olsen died in 1967, he left behind the unfinished Kalaallisut translation of Bahá’u’lláh and the New Era. Olsen’s work was finally finished in 1985 and the book was published that July through the Kalaallit Nunaanni Naqiterisitsarfik (the Greenlandic Publishing House), with advertisements placed in A/G.77

The growth of the Bahá’í community by the early 1980s sparked thoughts of minting Greenland’s own National Spiritual Assembly. To aid in this process, the community looked to establish Local Spiritual Assemblies outside of Nuuk, with Sisimiut being the first target in 1983.78 The Sisimiut Assembly was operational by 1986, representing ‘a foundation for the formation of a National Spiritual Assembly’. This coincided with ‘a very satisfactory increase in the number of new believers’ in Greenland. The volume of The Bahá’í World covering this period contains a report stating that the ‘spiritual floodgates have opened on this country, as can be witnessed by recent unprecedented growth’, marking ‘the beginnings of a true national community’.79

Lotus Nielsen moved to Sisimiut in 1988 to aid the consolidation efforts there, and again moved to Aasiaat in 1990 to work towards the creation of Greenland’s third Local Spiritual Assembly. She died in Nuuk on 25 October 1991. One of her daughters reported that some of her last words, spoken upon hearing of the successes enjoyed by the teaching project in Aasiaat, were: ‘Now we will get our National Assembly!’80

An upwards trend continued into the early 1990s, as demonstrated by a seminar titled ‘Spirit North II’ held in Nuuk in July 1991. This was the largest Bahá’í event in Greenland to date, being attended by 41 adults and 24 children, with visiting representatives from Alaska, Canada, Denmark, Iceland, and the United States.81

Finally, in 1992, Greenland’s Bahá’ís were sufficiently numerous and organised to set up a National Spiritual Assembly,82 with the first National Convention occurring on 25 April 1992. Hand of the Cause ʻAlí-Muhammad Varqá travelled to Nuuk for this event.83 The NSA was complete with its own National Teaching Committee for consolidation and outreach work. The Committee quickly set about reaching the city of Tasiilaq, the most populous settlement on the eastern coast of Greenland, with a view to forming a Local Spiritual Assembly there.84

‘Dogged perseverance’ (1992-2024)

The general patterns of Bahá’í life in Greenland had now been set – teaching endeavours, participation in arts and culture events, social justice advocacy, and gradual expansion into new settlements. Recent developments have largely consisted of the solidification of these patterns and their application across a broader geographical area.

In one particularly noteworthy instance, Nuuk’s Bahá’í community worked with the singers Juaaka Lyberth and Rasmus Lyberth as well as with other religious organisations, particularly the Catholic Church, to organise a rally against racism in the city on Sunday, 17 January 1993, to mark Martin Luther King Jr. Day (18 January). 300 people gathered in the dark of the afternoon to light candles and sing songs, including the popular US civil rights song ‘We Shall Overcome’ and the Greenlandic song ‘Eqqissineq’ (‘Peace’), set to the melody of ‘Amazing Grace’. The rally was recorded by the country’s television company KNR-TV and broadcast to the nation the next day.85

Growing visibility in the national media was a consistent theme in the 1990s. Grace Nielsen, daughter of Lotus Nielsen, caught the attention of A/G in February 1994 with the story of how she received a package from Iceland containing a teddy bear named ‘Rudo’ (meaning ‘love’ in the Shona language). Rudo came from a Bahá’í youth project in Botswana and Zimbabwe. The project involved sending the elephant-like soft toy around the world and receiving ‘reports’ about Rudo’s adventures from the Bahá’í community in each destination. Nielsen decided to send Rudo to Denmark for his next adventure.86

Outreach activities also continued apace: For instance, Margrethe Nielsen, a member of the Greenlandic NSA, delivered a talk on the Bahá’í Faith to around 50 school students on 17 March 1994.87 A group of five Canadian youth came to Greenland that summer and helped spread the word in Nuuk and a number of smaller settlements. Around the same time, the Bahá’í community of Nuuk sponsored an art exhibition at Greenland’s National Museum showcasing pieces by the Canadian Gary Berteig and the Greenlander Linda Milne. First-day attendance was reported by Bahá’í sources to be 380, while ‘the opening remarks made it clear that the figure of Baha’u’llah was the animating force behind the artists’ work and the exhibition itself’.88

Local consolidation was a priority for the young NSA of Greenland. Tasiilaq’s budding Bahá’í community, for example, enjoyed steady growth throughout the 1990s, conducting its first Summer School in July 1995.89 Together with two travelling teachers, including Nuka Møller, now a member of the Greenlandic NSA, the small community also observed the Feast of Kalimát (or Feast of Words) on the first day of the month of Kalimát in the Bahá’í calendar.90

The Universal House of Justice issued a supplementary statement in 1996 remarking upon the successes of Greenland’s Bahá’ís:

Our thoughts turn often to the Bahá’í community of Greenland, whose staunchness of faith and dogged perseverance have won our admiration and praise, and have resulted in the Faith’s becoming firmly established in that distant land. Inspired by the promise set out in the Tablets of the Divine Plan that “if the hearts be touched with the heat of the love of God, that territory will become a divine rose-garden and a heavenly paradise, and the souls, even as fruitful trees, will acquire the utmost freshness and beauty,” let them now go forth to claim new victories on the home front and to transform their nation through the power of the Divine Teachings.91

In 1996-7 the Greenlandic NSA appointed a board of directors to its training institute, enabling it to offer more advanced courses to its members.92 The first batch of courses became available in July 1997 in Kalaallisut, Danish, and English,93 and in 1998-9 Bahá’í authorities reported ‘an exponential rise in Bahá’í activity this year in the form of traveling teachers and regular public talks’.94 Modern technologies were also making information more easily available to Greenlandic and Inuit-Canadian Bahá’ís during this time, not least the official Bahá’í website, which went live in 1996.95 Bahá’ís in Canada’s Northwest Territory launched a CD in July 1998 featuring Bahá’í scriptures spoken in Inuinnaqtun, an Inuk language related to Kalaallisut.96

Ties with Inuit-Canadian Bahá’í communities were strengthened further by mutual participation in international initiatives,97 including a development conference in Florida in February 1999 at which the Greenlander Anaangaq Lyberth demonstrated traditional Inuit drumming and chanting.98 The most significant of these was arguably the inaugural Circumpolar Bahá’í Conference (subtitled ‘Creating a Culture of Growth in the Circumpolar Regions’) in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, held in September 1999,99 where representatives from across the region deliberated upon unified strategies for planting ‘Bahá’í communities over the top of the globe’.100

There were by this stage enough Greenlandic Bahá’ís to organise independent teaching expeditions without foreign assistance. One such expedition, organised by the Youth Wing of the Permanent Institute for the Bahá’ís of Greenland, conducted courses for three weeks in Sisimiut, focusing on the concept of ‘deepening’ (i.e., attaining a deeper understanding of the Bahá’í faith).101

In March 1999 the Nuuk Local Spiritual Assembly placed an advertisement in A/G for an event celebrating its 20th anniversary at the Katuaq cultural centre.102 Celebrations in August attracted prominent Bahá’í figures from Canada and Denmark.103 A depth of artistic and musical talent in the community helped it to see out the twentieth century with a flurry of positive media exposure, including a two-part profile of the life of Jim Milne, an Inuit musician and a continuous member of the Nuuk Local Spiritual Assembly since 1979.104

The new century began with the deaths of two significant figures in Greenlandic Bahá’í history – one was Peggy Ross, who began teaching in Greenland in 1971;105 the other was Palle Bischoff, who had been the first Baháʼí resident in Greenland in 1951-4.106 The century also began, of course, with a world-shaking terrorist attack in the United States on 11 September (or 9/11) 2001. In its first-ever address to all Greenlanders, the Greenlandic NSA issued a statement expressing ‘heartfelt condolences for those innocent victims who were struck down by shameless acts of terrorism’. It added: ‘Our beloved country also needs to join hands with the other governments as a nation and participate fully in raising the standard of justice and peace amongst all nations.’ The statement was published in A/G in both Danish and Kalaallisut.107

The 9/11 statement can be seen as the beginning of a more proactive international role for the Greenlandic NSA. Two Greenlandic Bahá’ís, Ruth and Stephan Montgomery-Andersen, represented Greenland at the March 2009 session of the UN Permanent Commission on the Status of Women in New York. The meeting was structured around the theme: ‘The equal sharing of responsibilities between women and men, including caregiving in the context of HIV/AIDS.’ Serving as part of the International Bahá’í Community delegation, Ruth and Stephan delivered a presentation based on research interviews with Greenlandic women on the subject of HIV/AIDS.108

Today, modern communications technologies and social media platforms are helping the Greenlandic Bahá’í community overcome some of the inherent challenges involved in living as part of a highly dispersed population where transportation is both long and intermittent.109 These platforms have also made it easier to connect with the global Bahá’í community. For instance, in 2016 the Nuuk Bahá’ís organised a celebration event to mark the centenary of the 1916 Tablet in which ʻAbdu’l-Bahá had called for pioneers to go to Greenland, and this story was shared with Bahá’ís across the world through a popular Facebook group.110

In October 2017 and October 2019, partaking in global celebrations of the bicentenary of the births of the ‘Twin Luminaries’ Baháʼu’lláh and the Báb, the Bahá’ís in Nuuk organised special events with traditional Inuit drum dancing and Inuit food. Over 100 people reportedly attended the October 2019 event, with government officials also being invited. Local Bahá’í organisations elsewhere in Greenland held smaller concurrent events. Photographs of these celebrations were posted to the official bicentenary website.111

With a firm foundation in Nuuk and several other settlements, the Bahá’í Faith is in a strong position to continue to grow as the twenty-first century progresses. The rate of growth may depend on its ability to capitalise on the message of unity that has proved so attractive in the past, and on its ability to maintain relevance in a religious ecosystem that is only becoming more diverse. The official Bahá’í website’s description of the current goals of the Bahá’ís in Greenland offers an apposite note on which to close:

Here, members of the Bahá’í community are working together with their neighbors and friends to promote and contribute to the well-being and progress of society. In urban centres and rural villages, in homes and schools, citizens of all backgrounds, classes and ages are participating in a dynamic pattern of life, taking part in activities which are, at once, spiritual, social and educational.112

Notes

- F. A. J. Nielsen, ‘Religion and religious communities’, Trap Greenland, 2021. https://trap.gl/en/kultur/religion-og-trossamfund/ ↩︎

- T. Lawson, ‘Baha’i religious history’, Journal of Religious History, vol. 36, no. 4, 2012, pp. 463-70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9809.2012.01224.x ↩︎

- C. Buck, Baha’i Faith: the Basics (Abingdon: Taylor & Francis, 2020), p. 35. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 1-7. ↩︎

- Star of the West, vol. 1, no. 4, 17 May 1910, p.16. https://bahai.works/Star_of_the_West/Volume_1/Issue_4 ; ‘Site of the Mashrak-el-Azkar in America’, Star of the West, vol. 3, no. 12, 16 October 1912, p. 2. https://bahai.works/Star_of_the_West/Volume_3/Issue_12 ↩︎

- The Bahá’í World vol. 7, 1936-1938 (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1939), p. 210. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_7/Excerpts_from_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_Sacred_Writings ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 211. ↩︎

- E. G. Cooper, ‘The new work now before us’, Star of the West, vol. 7, no. 11, 27 September 1916, p. 102. https://bahai.works/Star_of_the_West/Volume_7/Issue_11/Text ↩︎

- ‘The Teaching Campaign’, Star of the West, vo. 7, no. 12, 16 October 1916, p. 112. https://bahai.works/Star_of_the_West/Volume_7/Issue_12/Text ↩︎

- K. Kjærgaard, ‘Mellem sekulariseret modernisme og bibelsk fromhed: Fromhedsbilleder og moderne kirkekunst i Grønland 1945–2008’, Fortid og Nutid: Tidsskrift for kulturhistorie og lokalhistorie, June 2009, no. 2, pp. 108, 113. https://tidsskrift.dk/fortidognutid/article/view/75443 ↩︎

- M. L. Root, ‘The soul of Iceland’, The Bahá’í World 1934-1936 (New York: Bahá’í Publishing Committee, 1937). https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_6 ↩︎

- S. A. Coblentz, ‘While armies grow’, World Unity, vol. 13, no. 2, November 1933, p. 74. https://bahai.works/World_Unity/Volume_13/Issue_2 ; E. P. Kimball, ‘Sociology and world unity’, World Unity, vol. 15, no. 3, December 1934, p. 141. https://bahai.works/World_Unity/Volume_15/Issue_3 ↩︎

- ‘Race unity’, Bahá’í News, no. 137, July 1940, p. 8. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_137 ↩︎

- I. Hjelme, ‘Johanne Høeg, 1891-1988’, in The Bahá’í World vol. 20, 1986-1992 (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1998), p. 924. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_20/Johanna_H%C3%B8eg ↩︎

- ‘The Guardian’s Message to the Thirty-Ninth Annual Bahá’í Convention’, Bahá’í News, no. 195, May 1947, p. 6. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_195 ↩︎

- ‘The Guardian’s message to the Forty-first Annual Bahá’í Convention 1949’, Bahá’í News, no. 219, May 1949, p. 1. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_219 ↩︎

- S. Effendi, The challenging requirements of the present hour (Wilmette, IL: National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States and Canada, 1947), p. 10. https://bahai.works/The_Challenging_Requirements_of_the_Present_Hour ↩︎

- ‘The challenging requirements’, Bahá’í News, no. 198, August 1947, p. 8. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_198 ↩︎

- ‘Guardian’s Cable to Canadian Convention’, Bahá’í News, no. 207, May 1948, p. 3. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_207 ↩︎

- ‘Canada’, Bahá’í News, no. 210, August 1948, p. 7. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_210 ↩︎

- ‘“This hour, crowded with destiny”’, Bahá’í News, no. 224, October 1949, p. 3. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_224 ↩︎

- The Guardian reviews world progress of the faith in message to Convention’, Bahá’í News, no. 232, 25 April 1950, p. 1. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_232 ↩︎

- C. Linfoot, ‘Convention Report – 1950’, Bahá’í News, no. 232, 25 April 1950, p. 4. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_232 ↩︎

- M. Warburg, Citizens of the world: A history and sociology of the Baha’is from a globalisation perspective (Leiden: Brill, 2006), p. 203. ↩︎

- S. Effendi, Messages to Canada (Montréal: National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’is of Canada, 1965), p. 73. https://bahai-library.com/shoghi-effendi_messages_canada ↩︎

- ‘Canada’, Bahá’í News, no. 246, August 1951, p. 11. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_246 ↩︎

- ‘Greenland’, Bahá’í News, no. 251, January 1952, p. 11. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_251 ↩︎

- Effendi, Messages to Canada, pp. 24, 26. https://bahai-library.com/shoghi-effendi_messages_canada ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 28. ↩︎

- N. G. R. Tinnion, ‘John Aldham Robarts, Knight of Baháʼu’lláh, 1901-1991’, The Bahá’í World vol. 20, pp. 803-4. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_20 ↩︎

- B. D. Harper, Lights of fortitude: Glimpses into the lives of the hands of the cause of God (Oxford: George Ronald, 1997), p. 483. ↩︎

- ‘The Guardian announces series of five intercontinental conferences and appointment of eight additional hands of the cause’, insert in Bahá’í News, no. 321. November 1957. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Inserts/Issue_321/The_Guardian_Announces_Intercontinental_Conferences_and_Appointment_Hands_of_the_Cause ; ‘Reports of the All-America Intercontinental Teaching Conference’, The Bahá’í World vol. 12, 1950-1954 (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1956), p. 146. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_12 ↩︎

- Effendi, Messages to Canada, p. 37. https://bahai-library.com/shoghi-effendi_messages_canada ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 48. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 61. ↩︎

- ‘Obituaries, Palle Bischoff’, in The v World vol. 30, 2001-2002 (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 2003), p. 303. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_30/Obituaries ↩︎

- ‘The Guardian’s message to the Forty-ninth Annual Convention of the Bahá’ísof the United States’, insert in Bahá’í News, no. 315, May 1957. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Inserts/Issue_315/The_Guardian%E2%80%99s_Message_to_the_49th_Annual_Convention ↩︎

- Effendi, Messages to Canada, pp. 67-8. https://bahai-library.com/shoghi-effendi_messages_canada ↩︎

- ‘Canada’, Bahá’í News, no. 298, December 1955, p. 5. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_298 ; This claim is repeated (as of 18 December 2024) in the entry for ‘Greenland’ on Bahaipedia, a collaborative Bahá’í encyclopaedia. https://bahaipedia.org/Greenland ↩︎

- Effendi, Messages to Canada, p. 74. https://bahai-library.com/shoghi-effendi_messages_canada ↩︎

- ‘Rapid world-wide extension of the Faith’, The Bahá’í World vol. 12, p. 54. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_12 ↩︎

- ‘Obituaries, Hendrik Olsen’, The Bahá’í World vol. 14, 1963-1968 (Haifa: The Universal House of Justice, 1974), pp. 369-70. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_14 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 370. ↩︎

- ‘Greenland enrolls first native believer’, Bahá’í News, no. 417, December 1965, p. 10. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_417 ↩︎

- Bahá’í News, no. 419, February 1966, p. 6. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_419 ↩︎

- G. J. Nielsen, ‘Lotus Nielsen, 1925-1991’, The Bahá’í World vol. 20, 1986-1992 (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1998), pp. 1019-20. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_20 ↩︎

- ‘North Atlantic Oceanic Conference’, Malaysian Bahá’í News, vol. 7, no. 3, October 1971, p. 12. https://bahai.works/Malaysian_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Volume_7/Issue_3 ; For the list of names of the participants, see A. Jennrich, ‘About the North Atlantic Oceanic Conference – Reykjavik, Iceland’, Bahá’í News, no. 488, November 1971, p. 25. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_488 ↩︎

- ‘Spotlight on Greenland’, Bahá’í News, no. 488, November 1971, p. 22. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_488 ↩︎

- ‘Lotus Nielsen’, The Bahá’í World vol. 20, p. 1020. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_20 ↩︎

- ‘First conference held in Arctic, sub-Arctic region’, Bahá’í News, no. 525, December 1974, pp. 8-9. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_525 ↩︎

- ‘Greenland: Ḥaẓíratu’l-Quds in capital city acquired’, Bahá’í News, no. 527, February 1975, pp. 3-4. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_527 ↩︎

- ‘Iceland: Mr. Sears visits temple site and Youth Conference’, Bahá’í News, no. 533, August 1975, p. 18. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_533 ↩︎

- ‘Greenland: Danish settlement receives message’, Bahá’í News, no. 537, December 1975, pp. 14-15. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_537 ↩︎

- ‘Alaska’, Bahá’í News, no. 589, April 1980, p. 14. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_589 ↩︎

- ‘Council draws 85 Native American believers’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 9, Special Teaching Edition, 17 October 1978, p. 3. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_9/October_Special ↩︎

- ‘Native Council’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 11, September 1980, p. 12. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_11/September ↩︎

- ‘Around the world’, Bahá’í News, no. 591, June 1980, p. 10. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_591 ↩︎

- ‘To the International Teaching Conference in Helsinki, Finland, 5-8 July 1976’, The Bahá’í World vol. 17, 1976-1979 (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1981), p. 130. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_17 ↩︎

- ‘Greenland’, Bahá’í News, no. 585, December 1979, p. 15. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_585 ↩︎

- ‘Baha’i har oprettet åndeligt råd i Nuuk’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 119, no. 23, 7 June 1979, p. 6. https://timarit.is/page/3801132 ↩︎

- ‘Bahá’í’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 119, no. 30, 26 July 1979, p. 23. https://timarit.is/page/3801346 ↩︎

- ‘Bahá’í’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 120, no. 9, 28 February 1980, p. 22. https://timarit.is/page/3802247 ↩︎

- ‘Greenland’, Bahá’í News, no. 598, January 1981, p. 13. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_598 ↩︎

- ‘Young people’s activities’, Bahá’í News, no. 607, October 1981, p. 5. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_607 ↩︎

- ‘Greenland’, Bahá’í News, no. 615, June 1982, p. 12. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_615 ↩︎

- ‘Greenland’, Bahá’í News, no. 624, March 1983, p. 14. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_News/Issue_624 ↩︎

- ‘Verdens mest fremtrædende BAHA’I besøger Grønland’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 122, no. 37, 15 September 1982, p. 5. https://timarit.is/page/3807876 ↩︎

- ‘International survey of current Bahá’í activities’ and ‘The world order of Baháʼu’lláh’, The Bahá’í World vol. 18, 1979-1983 (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1986), pp. 190-2, 509. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_18 ↩︎

- ‘Bahá’í’-religionen vinder frem i Arktis’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 122, no. 44, 17 November 1982, p. 8. https://timarit.is/page/3808242 ↩︎

- K. Peterson, ‘Kristumiut oqaluffii akkunnerminni akkuerisaat’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 137, no. 17, 4 March 1997, p. 20. https://timarit.is/page/3845887 ↩︎

- ‘Bahai-mik upperisalik Nuka Møller: Oqaluffeqanngilagut aamma palaseqanngilagut’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 126, no. 50, 10 December 1986, p. 8. https://timarit.is/page/3817083 ↩︎

- ‘Hilsen’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 128, no. 17, 11 March 1988, p. 2. https://timarit.is/page/3819480 ↩︎

- ‘Eighth Greenlandic Summer School set’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 19, no. 6, June 1988, p. 19. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_19/Issue_6 ↩︎

- ‘World news’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 22, no. 7, July 1991, p. 27. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_22/Issue_7 ↩︎

- ‘To unge kunstnere’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 124, no. 39, 26 September 1984, p. 52. https://timarit.is/page/3812984 ↩︎

- ‘Encouraging Cultural Activities in Greenland’, One Country, vol. 1, no. 1, Winter 1989, p. 10. https://bahai.works/One_Country/Volume_1/Issue_1 ↩︎

- ‘John E. Esslemont: Baháʼu’lláh’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 125, no. 28, 10 July 1985, p. 11. https://timarit.is/page/3814700 ↩︎

- ‘Summer projects beckon to travelling teachers’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 14, May 1983, p. 8. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_14/May ↩︎

- ‘Survey of continents’ and ‘The world order of Baháʼu’lláh’, The Bahá’í World vol. 19, 1983-1986 (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1994), pp. 173, 477. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_19 ↩︎

- ‘Lotus Nielsen’, The Bahá’í World vol. 20, pp. 1020-1. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_20 ↩︎

- ‘World news’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 22, no. 10, October 1991, p. 11. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_22/Issue_10 ↩︎

- ‘121: Message on the Day of the Covenant’, Messages from the Universal House of Justice, 1986-2001 (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 2009), p. 246, para. 121.1a. https://bahai.works/MUHJ86-01/121/Message_on_the_Day_of_the_Covenant ↩︎

- ‘The world order of Baháʼu’lláh’, The Bahá’í World vol. 20, p. 670. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_20 ↩︎

- ‘World news’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 23, no. 17, 23 November 1992, p. 11. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_23/Issue_17 ↩︎

- ‘Et lys blev tændt i mørket’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 133, no. 8, 20 January 1993, p. 16. https://timarit.is/page/3834460 ↩︎

- ‘Hallo – vi har en pakke til dem fra Island’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 134, no. 14, 22 February 1994, p. 24. https://timarit.is/page/3837729 ↩︎

- ‘World news’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 25, no. 8, 5 June 1994, p. 15. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_25/Issue_8 ↩︎

- ‘Bahá’í youth’ and ‘The Language of the heart: Arts in the Bahá’í World Community’, The Bahá’í World vol. 23, 1994-1995 (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1996), pp. 171-2, 262. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_23 ↩︎

- ‘The year in review’, The Bahá’í World vol. 24, 1995-1996 (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1997), p. 109. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_24 ↩︎

- ‘News from overseas’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 26, no. 8, 16 October 1995, p. 21. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_26/Issue_8 ↩︎

- ‘220: Supplementary Message—Riḍván Message 1996—Europe, Ridván 153’, Messages from the Universal House of Justice, 1986-2001 (Wilmette, IL: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 2009), p. 510, para. 220.13. https://bahai.works/MUHJ86-01/220/Supplementary_Message-Ri%E1%B8%8Dv%C3%A1n_Message_1996-North_America ↩︎

- ‘The year in review’, The Bahá’í World vol. 25, 1996-1997 (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1998), p. 108. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_25 ↩︎

- ‘The year in review’, The Bahá’í World vol. 26, 1997-1998 (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1999), pp. 92-3. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_26 ↩︎

- ‘The year in review’, The Bahá’í World vol. 27, 1998-1999 (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 2000), p. 117. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_27 ↩︎

- ‘The Bahá’í World on the World Wide Web’, The Bahá’í World vol. 25, p. 158. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_25 ↩︎

- ‘CDs feature writing in Arctic language’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 29, no. 8, 16 October 1998, p. 35. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_29/Issue_8 ↩︎

- ‘Counselors boost race unity drive’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 29, no. 3, 9 April 1998, pp. 1, 23. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_29/Issue_3 ↩︎

- ‘The performances’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 30, no. 1, 7 February 1999, p. 23. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_30/Issue_1 ↩︎

- ‘The year in review’, The Bahá’í World vol. 28, 1999-2000 (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 2001), p. 62. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_28 ↩︎

- ‘Conference brings together friends from northernmost regions of the globe’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 30, no. 10, 31 December 1999, p. 31. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_30/Issue_10 ↩︎

- ‘Teaching’, The American Bahá’í, vol. 30, no. 5, 24 June 1999, p. 63. https://bahai.works/The_American_Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD/Volume_30/Issue_5 ↩︎

- ‘Katuaq: 16.-23. MARTS’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 139, no. 21, 16 March 1999, p. 21. https://timarit.is/page/3851636 ↩︎

- ‘Jubilæum i Bahá’í-samfundet i Nuuk’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 139, no. 61, 12 August 1999, p. 18. https://timarit.is/page/3852768 ↩︎

- J. Brønden, ‘Jeg har altid været omgivet af de bedste’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 139, no. 33, 29 April 1999, p. 13. https://timarit.is/page/3851947 ; J. Brønden, ‘Til Grønland ved en tilfældighed’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 139, no. 35, 6 May 1999, p. 14. https://timarit.is/page/3851997 ↩︎

- ‘Obituaries, Peggy Ross’, The Bahá’í World vol. 28, p. 62. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_28 ↩︎

- ‘Obituaries, Palle Bischoff’, The Bahá’í World vol. 30, 2001-2002 (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 2003), p. 303. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_30 ↩︎

- ‘The year in review’, The Bahá’í World vol. 30, pp. 92-3. https://bahai.works/Bah%C3%A1%E2%80%99%C3%AD_World/Volume_30 ↩︎

- ‘Grønland repræsenteret i FN-konference’, Sermitsiaq, 7 March 2009. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/gronland-repraesenteret-i-fn-konference/273288 ↩︎

- International Teaching Centre, The five year plan 2011-2016: Summary of achievements and learning (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 2017), pp. 43-4. ↩︎

- S. Emmel, ‘Presenting the deeply-loved and most precious Baha’i community of Nuuk, Greenland’, Facebook, 5 April 2016. https://www.facebook.com/groups/2209644753/posts/10154039354279754/ ↩︎

- ‘Greenland: Stories of celebration’, Bicentenary of the Birth of Baháʼu’lláh, as of 19 December 2024. https://stories.bicentenary.bahai.org/greenland/ ↩︎

- ‘A global community: Greenland’, Bahai.org, as of 19 December 2024. https://www.bahai.org/national-communities/greenland ↩︎

2 responses to “The Bahá’í Faith in Greenland”

[…] being opened in Inuvik in Canada’s Northwest Territories in 2010.2 Despite the success of the Bahá’í Faith, a close cultural relative of Islam, Greenland has never had a significant Muslim […]

LikeLike

[…] monopoly was abolished in 1953 – including Catholics, Adventists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Bahá’ís – the Pentecostal movement was one of the few that the Church viewed as a serious threat. This […]

LikeLike