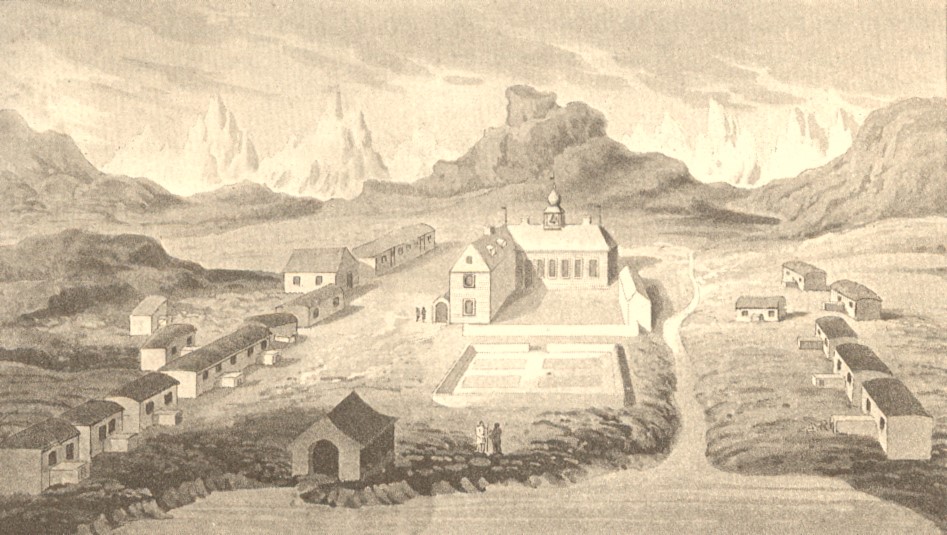

The Moravian mission station at New Herrnhut, Nuuk. From Heinz Barüske’s Grönland: Kultur und Landschaft am Polarkreis. Wikimedia Commons.

No sooner had Christianity entrenched itself in the cultural firmament of Greenlandic society than had sprouted the first shoots of spiritual rebellion against the singular authority of the European missionaries. The Danish Lutheran community was the first to be established in the country in 1721, but the Moravian Brethren community at New Herrnhut (in modern-day Nuuk), set up in 1733, was the first to witness a concerted effort at a schism.

‘Visionary doctrines’

Moravian missionary to Greenland David Crantz records the following episode in his account of the year 1768:

While the Brethren were out fishing in the Sound, a Greenlander began to preach certain visionary doctrines, whereby he collected a number of admirers and unsettled some weak and unsteady minds. The missionaries could not at once put a stop to his unprofitable discourse, but admonished the national assistants to keep a watchful eye upon him, and warn the simple not to pay too much attention to his fanciful speculations. In this way the sectarian spirit which seemed ready to creep in, even amongst Greenlanders, was nipped in the bud.1

The Moravian Crantz does not elaborate on the specifics of this sect, the contents of the ‘visionary doctrines’, what caused it to break away, or what the leaders claimed about the root of their own authority. It is strikingly similar to a later recollection of a spiritual movement that briefly split from the Danish mission in Kangersuatsiaq (The Fjord of Eternity) in 1788–90, when an Inuit Christian couple by the names of Mary Magdalene and Habakkuk (or Jesus) commanded a sizeable breakaway congregation and based their authority on a claim to have received certain theophanies and powers from the Heavens.

The 1768 rebellion also resembles in many aspects the saga of Mathæus, an Inuit Christian who in the winter of 1853–4 proclaimed himself to be the archangel Gabriel and led away a sect of followers from the Moravian mission at Friedrichsthal (modern-day Narsarmijit) on the southern tip of Greenland.

All three of these sects are notable for the direct challenge they posed to the sole European leadership of the Christian communities of Greenland, and for their elevation of Inuit individuals to positions of clerical or prophetic authority. All three involved the decampment of a portion of a mission station’s inhabitants to a different location where they could be free from the daily supervision of the Europeans and their loyal Inuit catechists. All three eventually evaporated once the initial enthusiasm had worn off, the followers streaming back into the European mission stations to resume their former lives. And all three — but particularly those of Habakkuk and Gabriel — are based on a very loose theology in which the roles of specific persons, such as those of Jesus and God’s angels, are morphed and merged, to fit established motifs from traditional Inuit shamanism and to bestow near-boundless power upon the sect’s leaders.

Mary and Habakkuk

The story of Mary and Habakkuk was recorded in two main formats: first, a series of reports by the Danish missionary Niels Hveyssel to the Missionary Department in Copenhagen during the time of the schism; and second, a transcription of an Inuit account told to the Danish geologist and administrator Hinrich Rink, first published in Danish in 1857 and English in 1877.

Hveyssel’s first report in 1778 informed the Missionary Department that the whole affair began when Mary Magdalene — an Inuit woman jealous of the attention given by her husband Habakkuk to his second wife Alhed — wrote to Hveyssel via the delivery of Habakkuk that she had had visions of a deceased couple, from whom she received prophetic information concerning the living and the dead.2 Hveyssel tried to dissuade Habakkuk from partaking in such heresies, but Magdalene soon developed a three-point religious doctrine which is summarized here by historian Christina Petterson:

(1) that she has been commanded by the deceased to ‘spread’ the errors of her neighbours; (2) that she has been told by the deceased that the dead have not received a new dwelling, but are in a ‘cheerless condition’; and (3) that the man who remarries after the death of his first wife only borrows the second, in that he will be reunited with the first in the afterlife.

Hveyssel, as a Protestant missionary, was alarmed by the seeming implication that the dead had not yet received their permanent residence in the afterlife, an idea with parallels to the Roman Catholic notion of Purgatory. His next report in 1779 details the beginnings of a mass movement, complete with shared visions of the dead and collective hearings of phantom hymns and the tolling of bells.

As soon as it was heard for the first time in Kangerdlugssuatsiaq, Habakuk’s wife, Mary Magdalene, about whom I reported last year, pretended to have secret conversations with the dead, who let her know that Judgement Day was at hand; that God was angry with their disbelief (which two years ago had contradicted her, when she had pretended to have had similar revelations) and their godlessness, which mainly was that they had neglected the good Moravian customs, which the late Hr Laersen had implemented.

The allusion to ‘Moravian customs’, which had many distinguishing features including the use of lots to make major personal and communal decisions,3 introduces a new dynamic, as the sect is now positioned as a betrayal of the Danish Lutheran way in favour of the rival German Moravian pietism. These events further strengthened Magdalene’s position, as Hveyssel reports that ‘the Greenlanders now could believe her words, God had sent a great host of dead people, so that they could hear and see for themselves’.4 Nor would they listen to Hveyssel’s direct admonitions, for Mary had

imprinted this notion in them, that should I or any other contradict her pretenses, they mustn’t answer, but immediately leave so as not to be corrupted by this ungodly speech. When something is said to them in admonishment, they should only answer: Kujanak (God’s will be done). They loyally follow her will, and when they can avoid contradiction in no other way, they begin singing one hymn after another.

Another Inuit Greenlander named Elijah had now begun to report similar visions which lent credence to those of the ‘wench’ and ‘seductress’. The situation was rapidly deteriorating, to the point that, according to Hveyssel, one of the Inuit catechists (trained clerical aids to the missionaries) by the name of Titus had been convinced to murder his own mother because Mary accused her of being a witch.5 This seems to have represented a high-point in the propagation of the schism, as by 1790 Hveyssel could report that the majority of the followers of Mary and Habakkuk had returned to the mission station, though the leaders carried forward their prophetic role for some time:

Habakuk and his wife are the only ones who will not let themselves be brought to repent, but this is much less significant, since they are abandoned by all the Greenlanders, even his own brothers. The violent behaviour of the man towards the Greenlanders was really what caused them to open their eyes and pull away from him.6

This is where Hveyssel’s telling of the story ends. The head of the Missionary Department in Copenhagen, Otho Fabricius, was very critical of his handling of the affair, believing him to be no ‘match for the wiles of this woman’ and even suggesting that he had played a role in maintaining her momentum by admitting in 1789 that he, too, had heard ‘something’ during the time of mass auditory apparitions.7

The version of the story told to Hinrich Rink by Inuit living in the area of the Mary/Habakkuk heresy in the mid-nineteenth century emphasises different components of the affair and introduces a number of elements not reported by Hveyssel. As Rink tells it:

In the summer of the year 1790 a woman named Maria Magdalena, living at the station of Sukkertoppen (65½° N. lat.), pretended to have had certain visions and revelations, and passed herself off as a prophetess. She directly made all the inhabitants of the place and its environs her adherents, and inspired them with an obedience sufficiently implicit to cause any person whom she might choose to point out to, be killed on the spot. It is said that two women were actually put to death by her in this way. She had for her husband a man named Habakkuk, whom, on account of his extreme devotion, she called Jesus, and he became the real head of the sect that formed a settlement at the fjord of Kangerdlugsuatsiak. This native community had completely separated from the mission, and their excesses greatly alarmed the Europeans in the country. But the sway of Habakkuk was only of short duration. He and his adherents having lost the guidance to which they had been accustomed from the European control, speedily proved like persons who have lost their wits. They fell into a kind of frenzy, and were soon subdued again. Their excesses, however, are still remembered by the population, and of the respect once paid to Habakkuk slight traces are still retained by his descendants.8

An Inuit resident who had gathered all the available information from his community told Rink that before the sect began in earnest Mary and Habakkuk had lost two children, which ‘made them very sad’, and that at the time of Mary’s first vision of a deceased couple Habakkuk had been temporarily paralyzed by supernatural forces. When Habakkuk’s second wife was pregnant, ‘they said that it was by the Holy Ghost, and if it proved to be a boy, he ought to be called Christ. But she bore a daughter.’

The sect’s other rituals included stoning ‘witches’ and throwing them into the sea, forming human rings and exchanging kisses around grave sites, and casting lots ‘to announce whom God favoured the most’. Habakkuk even began to speak in parables to his followers in the manner of Jesus, and to proclaim the commandments of the ‘chief persons in heaven’.

In this telling of the story, it was not Hveyssel’s admonitions or even a revulsion at the violence of the group that caused its downfall, but rather the intervention of an Inuit catechist named Naparutak, who interrogated Habakkuk as to why he had ‘altered the seventh commandment’ (concerning adultery). ‘When Habakkuk gave no answer, Naparutak very cautiously accosted him, admonishing him in a gentle manner, and desiring him to leave off his habits. From this time their pranks began to cease, but still they would remain superiors, being unwilling to yield.’9

There are signs that this story is either an amalgamation of multiple different oral traditions and/or that the theology of the sect was never settled. For instance, it is not clear if the group viewed ‘Jesus’ and ‘Christ’ as a single indivisible entity, since the signifiers of the Messiah seem to float around. The (imagined) male baby to be born to Habakkuk’s second wife, presumably via an immaculate conception, is to be called Christ, and yet it is Habakkuk who takes (or is given) the name, role, and authority of Jesus.

Habakkuk’s allusions to the ‘chief persons in heaven’ again raise more questions than answers. Is he referring to the Holy Trinity (three ‘chief persons’), or is the implication that there is a pantheon of ‘chief persons’ from whom Habakkuk, as Jesus (though not as God?), derives his spiritual standing on earth? It is also not clear if the names ‘Mary Magdalene’ and ‘Habakkuk’ have any particular significance — i.e., whether these names were given to them at birth (the names often being chosen by the missionaries, not the parents)10 or adopted at some point prior to the schism with some intentionality, perhaps with a view to mimicking the roles of these two biblical characters.

Finally, we are given no definite picture of the soteriological views of the sect — that is, how they thought salvation worked. The exact purposes of the gravesite rituals are mysterious, but they could have something to do with the spiritual condition of deceased souls, if Hveyssel’s account of the group’s views on heaven, hell, and an indeterminate space in-between is to be believed.

The ability to see the condition of the dead in the spirit world was one of the key ritual functions of the angekuit, or shamans, in the traditional religion of the Inuit. The significance of this particular motif in the Mary/Habakkuk story could be that it gives definite form and legitimacy to a practice of religious syncretism, meaning the combining of the new religion of the missionaries with the old religion of the angekuit, and hence a degree of cultural continuity or restoration — not, as Hveyssel worried, a turn to Catholic teachings that were, after all, absent in Greenland.

This would actually be consistent with the tendency of the missionaries to identify quick, easy parallels between Christian and Inuit spiritual concepts even where these comparisons were flawed. Inuit Christians had in a sense been trained into syncretism.11 Mary and Habakkuk ran with the intellectual tools that they had been handed and used them to build an Inuit-led hybrid of traditional and Christian religiosity, with some of their own ideas and off-the-cuff innovations sprinkled on top. However, given its apparently murderous inclinations towards ‘witches’, the sect does not easily lend itself to celebratory postcolonial reclamation as attempted by some modern authors such as the novelist Kim Leine.12

The Archangel rises

An equally ‘floaty’ theology is seen in the final sect, that of Mathæus/Gabriel. Rink again relates the story:

In the winter of 1853–4 the quiet life of the Moravian Brethren at Frederiksdal was disturbed in the most unexpected manner. … [I]t happened that a young man named Mathæus, distinguished not only by his skill in seal-hunting, but also most remarkably by his school-learning, and intended by the missionaries for a teacher, suddenly became taciturn and reserved, and often sought solitude. Some time later the Brethren perceived that unusual assemblies were being held in the houses of the natives, who at the same time neglected to attend the daily prayers. They were then informed that this Mathæus had assumed the authority of a prophet, and had resolved to form a community of his countrymen, quite independent of the Europeans. He believed that he had had visions and conversed with the Saviour; he adopted the name of Gabriel, and soon gathered around him a crowd of adherents who put implicit confidence in his words and promised obedience to his commands.13

The chosen name ‘Gabriel’ seems to be intended to impart upon this individual the identity and esteem of the archangel.14 This being the case, it is once again difficult to determine how the theological pieces should line up here. The storyteller’s specification that Mathæus was advanced in ‘school-learning’ and was ‘intended by the missionaries for a teacher’ should not necessarily be taken as a sign that he had advanced theological knowledge, as this was generally not highly valued nor encouraged by the Moravian mission.15

As with Mary/Habakkuk, we cannot be certain that the message of the sect has been perfectly preserved in oral tradition. These questions are thus somewhat open-ended: Is he literally an angel in human form, incarnated from birth for a particular function on earth, or is he a person who at some point was ‘possessed’ by said angel? And what is the end-goal of his sect?

The answer to the latter question is mercifully answered if we read on:

The mutiny now rapidly expanded and soon left the missionaries with but few followers [from an initial population of 222], the regular divine service and ecclesiastical discipline peculiar to the sect being entirely interrupted. Gabriel celebrated marriages and fulfilled other ecclesiastic duties, and sent off kayakers to other places for the purpose of enlisting votaries. Soon other individuals also spoke of having had revelations from heaven, and a sort of feverish frenzy seized the whole population. Some of them wounded their hands, asking others to suck them for the purpose of trying the sweetness of the Saviour’s blood, others again were told to open their mouths, whereupon Gabriel breathed into it in order to impart to them the ‘Spirit.’

A grand project was planned, the whole band intending to depart in spring for the east coast, to go and convert the heathens and form a colony there. … Once Gabriel predicted that the world would come to an end in the ensuing night, and they threw all their implements out of their houses in order to be free from worldly riches at the setting in of the catastrophe. As, however, there was no sign of the world being destroyed, on the following day Gabriel, with some companions, climbed a wall, thinking they were going to ascend to heaven. They all wore their smartest dresses, and were washed and clean, and, as no ascension took place, Gabriel took off his boots and walked barefooted in the snow, supposing some adherent filth to have prevented the miracle.16

In the course of time, the sect has taken on the appearance of what would now be dubbed an ‘end-times cult’, complete with an expectation that the faithful few will soon ascend into the Heavens in a manner similar to that described in 1 Thessalonians 4:16–17 in the New Testament. The passage reads: ‘For the Lord himself will descend from heaven with a cry of command, with the voice of an archangel, and with the sound of the trumpet of God. And the dead in Christ will rise first. Then we who are alive, who are left, will be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air.’ These words are commonly used as a justification for ‘rapture’ theologies.

A theme observed earlier, the meshing together of different biblical characters and functions, becomes only more pronounced in this part of the story, with ‘Gabriel’ apparently having the power to ‘impart the Spirit’ through his breath (something with no clear parallel in biblical angelology), and members of the congregation, perhaps all humans, having ‘the Saviour’s blood’ in their veins. Arguably more interesting, though, is the mention of a ‘grand project’, an Inuit-led mission to the still largely non-Christian inhabitants of East Greenland.

The ‘why’ of this project is not detailed. It may have had some connection with the coming end of the world; or, alternatively, this apocalypticism may have been a later innovation and the mission could have been purely for the benefit of the souls of the East Greenlanders. Had the sect survived and grown as a clear Inuit-led alternative to the European missions, it would have changed the entire face of Christianity in Greenland and perhaps even Arctic Canada. It was not to be, however:

The missionaries now had only one way to act, viz. to hold their peace and go on with gentleness until the paroxysm had exhausted itself. Laying hands on the ringleader during the prevailing sensation would have been dangerous, and rendered the evil still worse. The extravagant excitement soon subsided and gave way to a sort of languor. The missionaries availed themselves of the opportunity in order to strengthen the trust of the few who remained faithful to them, and Gabriel was gradually abandoned by his partisans. The remainder of them removed to a place named Komiut, where they wholly devoted themselves to their reveries and frantic imaginations. … In the ensuing summer the rest of the sect seems also to have been dispersed. Even Gabriel gave in and suffered himself to be duly wedded by the missionaries.17

A loyal Inuit catechist once more played a lead role in dissipating the enthusiasm of the schism, in this case Jacob Lund, who with the help of ‘agents’ among the sectarians convinced the greater part of them to relent.18

Common threads

One clear theme that runs through all three of these stories — the unspecified group with ‘visionary doctrines’ in 1768, the Mary/Habakkuk schism of 1788–90, and the exploits of Gabriel in 1853–4 — is the fact that each party felt the need to move out of the mission towns and set up independent settlements elsewhere. In doing so, they directly contravened the intentions of the missionaries to master the nomadic lifestyles of the Greenlanders and accustom them to a sedentary (and supervised) life.

This all stemmed from the attitudes of the Europeans towards their new Inuit flock. Hans Egede, who founded the Danish Lutheran mission in Greenland in 1721, praised the Greenlanders for their ‘regular and orderly behaviour’ and even, in light of a perceived tendency towards godly morality even without the influence of Christianity, described them as ‘a law to themselves’.19 However, he also observed that even the converted Greenlander received the Gospel ‘with a surprising indifference and coldness’.20 Egede resolved to overcome the itinerant lifestyle of the Inuit:

It would contribute a great deal to forward their conversion, if they could by degrees be brought into a settled way of life, and to abandon this sauntering and wandering about from place to place to seek their livelihood. … They should also be kept under some discipline, and restrained from their foolish superstitions, and from the silly tricks and wicked impostures of their angekkuts [shamans], which ought to be altogether prohibited and punished. Yet my meaning is, not that they, by force and constraint, should be compelled to embrace our religion, but to use gentle methods. … Else it would be the same imprudence as to throw good seed into thorns and briars, which would choke the seed.21

The Moravian missionaries made the same calculation. David Crantz wrote that the Inuit were particularly susceptible to the influence of witches, ‘thereby preventing them from a rational inquiry into the truths of Christianity’.22 Only through ‘the social order of civilized life’ under a ‘watchful eye’ could this waywardness be addressed.23 Both the Danish and Moravian missions struggled against the interests of the Danish Trading Company in Greenland to achieve this end, the latter being convinced that maintaining the roving lifestyle of the Greenlanders was the best way to extract a profitable trade from them.24

However, Crantz was also wary of making the transition to town life too quickly and without the proper apparatuses of surveillance and supervision, because ‘among heathen nations, when the numbers are too great in a single settlement, to be minutely inspected, disorder easily gains ground, and their propensity to their former savage practices, is cherished by mutual contagion’. He wrote this concerning the events of the year 1758, when the population of New Herrnhut was around 400, ten years before the sect with ‘visionary doctrines’ split from the mission community.25

While the manner in which he expressed this fear communicates clearly racist preconceptions, the underlying notion was sound — that gathering together a large number of people will tend to increase the opportunities for communal organisation, including organisation of a sort that contravenes the desires of the ruling authority, be it secular or religious.

Notes

- D. Crantz, The history of Greenland, including an account of the mission carried on by the United Brethren in that country, vol. 2 (London: Longman, Hurst, Reese, Orme, and Brown, 1820), pp. 255–6. ↩︎

- C. Petterson, ‘Colonialism and orthodoxy in Greenland’, Postcolonial Studies, vol. 15, no. 1, 2012, p. 69. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2012.658744 ↩︎

- E. Sommer, ‘Gambling with God: The use of the lot by the Moravian Brethren in the eighteenth century’, Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 59, no. 2, 1998, pp. 267–86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3653976 ↩︎

- Petterson, ‘Colonialism and orthodoxy’, p. 72 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 73 ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 74 ↩︎

- C. Petterson, The missionary, the catechist and the hunter: Foucault, Protestantism and colonialism (Leiden: Brill, 2014), pp. 27n and 39. ↩︎

- H. Rink, Danish Greenland: Its people and its products (London: Henry S. King & Co., 1877), pp. 152–3. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 153–6. ↩︎

- R. M. Søby, ‘Naming and Christianity’, Études/Inuit/Studies, vol. 21, nos. 1–2, 1997, pp. 293–301. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42869972 ↩︎

- B. Sonne, ‘Heaven negotiated. The realms of death in early colonial West Greenland’, Études/Inuit/Studies, vol. 24, no. 2, 2000, pp. 65–87. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42871297 ↩︎

- L. Jensen (2015) ‘Postcolonial Denmark: Beyond the rot of colonialism?, Postcolonial Studies, vol. 18, no. 4, 2015, p. 448. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2015.1191989 ↩︎

- Rink, Danish Greenland, pp. 156–7. ↩︎

- E. L. Jensen, K. Raahauge, and H. C. Gulløv, Cultural encounters at Cape Farewell: The East Greenlandic immigrants and the German Moravian mission in the 19th century (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2011), p. 223. ↩︎

- C. McLisky, “A hook fast in his heart”: Emotion and “True Christian Knowledge” in disputes over conversion between Lutheran and Moravian missionaries in early colonial Greenland’, Journal of Religious History, vol. 39, no. 4, 2015, pp. 586–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9809.12271 ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 157–8. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 158. ↩︎

- Jensen, Raahauge, and Gulløv, Cultural encounters, p. 224. ↩︎

- H. Egede, A description of Greenland (London: T. and J. Allman, 1818), p. 123. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 214–15. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 216–18. ↩︎

- D. Crantz, The history of Greenland, including an account of the mission carried on by the United Brethren in that country, vol. 1 (London: Longman, Hurst, Reese, Orme, and Brown, 1820), p. 152. ↩︎

- Crantz, The history of Greenland, vol. 2, pp. 90, 207. ↩︎

- Jensen, Raahauge, and Gulløv, Cultural encounters, pp. 132–41. ↩︎

- Crantz, The history of Greenland, vol 2, p. 149. ↩︎