Nuuk Art Museum, formerly the Seventh-day Adventist Chapel, in 2023. By Historica GL on Wikimedia Commons.

- Why did the Adventists want to reach Greenland?

- Early efforts to reach Greenland

- Advent of the Adventists

- Leaving and returning

- Why did Adventism fail in Greenland?

- Notes

Armageddon came to Greenland in 1953. The Seventh-day Adventists, a Christian denomination rooted in the conviction that the end of the present world is nigh, were the very first religious group to establish a foothold in Greenland after the Lutheran ecclesiastical monopoly was abolished in the new Danish Constitution. Missionaries from the Adventist Church rushed to bring Greenlanders the ‘advent hope’, the assurance that the travails and oppressions of the here-and-now were soon to be overcome, and within five years they had built a chapel and physiotherapy clinic in Nuuk, the nation’s capital city.

Adventism can be traced back to the writings of the nineteenth-century US end-times preacher William Miller, who predicted with reference to various numerical data points in the Bible that the Second Coming of Jesus, the annihilation of sinful souls, and the beginning (advent) of a new era under the reign of Christ would occur sometime in 1843–4. When his prediction failed, the Millerite movement came to know 1844 as the year of the ‘Great Disappointment’.1

The Seventh-day Adventist Church arose in the 1850s and 1860s from the rubble of Millerism, retaining a surety that Christ would return in the very near future but developing its own distinct doctrines, including a belief that the souls of the sinful would be permanently annihilated in the end-times (rather than continuing to exist in a hellish afterlife);2 observance of the Sabbath (a holy day of rest) on Saturday, the seventh day of the week, rather than Sunday;3 and a strong preference for vegetarian diets.4 A hubsand-and-wife pair, James and Ellen White, were among the movement’s early leaders. James founded the core periodical of the Church, The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, while Ellen became a prophetic and doctrinal authority through her writings, including The Great Controversy Between Christ and Satan (1858) and Steps to Christ (1892), which are core readings for Adventist believers.

Discussions about entering Greenland stretched back to the foundation of the movement. While it is not at all surprising that a fervently evangelistic church should desire to preach to the Greenlanders as much as to any other people, the sheer resolve behind this yearning was peculiarly acute among the Adventists. Their enthusiasm becomes especially noticeable when compared with other Christian movements that emerged during the nineteenth century. For instance, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (or ‘Mormon’ Church) has never opened an official branch in Greenland.

With time quickly running out before Christ’s anticipated return, Adventism’s message carries an inherent eschatological urgency which propels it at high velocity into every geographical crevice, yet this does not on its own answer the question as to ‘why’ it was so important to enter Greenland specifically, or why the intensity of the Adventists’ desire to reach Greenland was so disproportionate to the number of souls it contains (12,000 in 1900; 57,000 today). There are several territories of a similar population size where Adventists still have no presence at all, including the Mediterranean micro-state of Monaco and the island of Jersey in the English Channel. Not all ‘small’ nationalities are given the same attention.

Nor is Greenland’s allure explained solely by its romanticised status as a ‘remote’, ‘desolate’, and logistically challenging corner of the earth, as there has been no comparable effort to reach, say, the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic.5 Greenland was a high priority for the Adventists not because it was small and marginal and distant and hard to reach, but because it was central in three respects — central in the imaginations of white Christian evangelists as they pictured ‘savage’ and ‘uncivilised’ places, central on the world map, and central in the collective English-speaking Christian consciousness due to the popularity of the hymn ‘From Greenland’s Icy Mountains’.

Why did the Adventists want to reach Greenland?

Many of the earliest mentions of Greenland in official Adventist periodicals during the latter half of the nineteenth century present an exoticised picture of the Inuit, or ‘Eskimos’, as a hardy but impoverished group of ‘savages’.6 It was said that they suffered through the trials of life on their ‘bleak’ isle, far from civilisation.7 They were ‘little, dwarfed, oil-drinking, fish-eating bipeds’,8 inferior even to their maligned relatives in Alaska.9 According to Good Health, an Adventist journal edited by businessman and health reformer John Harvey Kellogg (founder of the Kellogg’s cereal brand), the ‘Eskimos’ of Greenland were not only ‘degenerated’, but ‘degenerating’ still more as the years passed, allegedly due to their meat-and-fish oriented diet of which the Adventists disapproved.10 Northeast Greenland in particular was said to be a place ‘where life is so cold and cheerless that people can hardly be said to live, but simply to exist’.11

Some of these impressions were gleaned from lectures delivered by Ólöf Krarer, an Icelandic woman and trickster who, under the pretence of being an ‘Eskimo’ from East Greenland, offered manufactured stories of unmitigated poverty and moral degeneracy in that region.12 Adventist magazines such as The Youth’s Instructor reported Krarer’s fabrications concerning her purported compatriots (the ‘lowest brutes’ who do not know the meaning of ‘washing’) as fact.13 In a long-form article in 1890, the Instructor quoted a remark from one of her lectures that could only be interpreted by this mission-oriented denomination as an invitation to proselytise among these seemingly desperate people: ‘Some day, some day, God will help them.’14 In its perceived need for the Adventist message, Greenland was assigned, at least rhetorically, a heightened priority.

The Adventist mind’s eye was also drawn to Greenland through maps. This Arctic island has a very prominent position on most flat maps of the world — even more so on Mercator Projection maps which greatly exaggerate the size of landmasses in the northern hemisphere, making Greenland look like an Africa-sized white blob towering over mainland North America. This observation seems rather basic, but its emotive power in missionary contexts can hardly be overstated. To not be there as an evangelising religious group with global ambitions leaves a giant blank space that represents a job unfinished.

Adventist deliberations concerning Greenland prior to the 1950s speak potently to this effect. In 1906, A. G. Daniells, president of the General Conference, gave a series of presentations at the Church’s global convention in Nebraska. As recorded by the Advent Review and Sabbath Herald (henceforth Review and Herald):

Nothing stirred the hearts of the people more than did the three earnest talks given by Elder Daniells on the progress of the work throughout the world. During one of these talks, he pointed out on the missionary map of the world that Greenland is the only country in the Western hemisphere where our work has not been opened. At this point in his address he was interrupted by the introduction of a resolution, recommending that the Nebraska Conference Committee appropriate from their surplus tithes the sum of fifteen hundred dollars to be used by the Mission Board in assisting to establish our work in Greenland. This appropriation, added to what was recommended at the Fremont and Aurora meetings, makes five thousand dollars that has thus far been appropriated to the Mission Board this season.15

A 1924 map charting the state of global Adventist missionary efforts published in the Review and Herald illustrates the point (see image below).16 Areas in which the Seventh-day Adventists already had a presence are represented in white, while areas in which they as yet had no presence at all are represented in black. Unpopulated and mostly unpopulated areas — primarily the Sahara Desert and the inner part of Greenland — are filled with a check pattern. Due to the use of the Mercator Projection of the globe onto a flat plane, Greenland deceptively looks to be by far the largest single territory lacking an Adventist mission. Evangelical completionism cannot tolerate so great a blot.

Another way in which the lack of a mission to Greenland played on Adventist minds is more ethereal but no less impactful. Written in 1819 by the Anglican Bishop of Calcutta in India, Reginald Heber, and set to the music of Lowell Mason’s Missionary Hymn, ‘From Greenland’s Icy Mountains’ is an imperialist-evangelistic song that was a regular feature in the services of many Protestant denominations in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Its first verse posits that Christians have a duty to reach people in every part of the globe and in every type of environment:

From Greenland’s icy mountains,

From India’s coral strand;

Where Afric’s sunny fountains

Roll down their golden sand:

From many an ancient river,

From many a palmy plain,

They call us to deliver

Their land from error’s chain.

Adventist writers in the early twentieth century often made note of the uncomfortable fact that their movement had not yet entered a country whose name their members sang so many times each year.17 When they finally did enter Greenland on a permanent basis in the 1950s, church historian H. L. Rudy declared joyously that ‘Adventists are at last justified in singing that well-known mission hymn “From Greenland’s Icy Mountains”’,18 while W. R. Beach wrote that they could ‘now sing “From Greenland’s Icy Mountains” with much more zest than ever they could before’.19 An article in the British Advent Messenger interpreted the mission to Greenland as a sign that God himself was projecting the movement forward: ‘From icy Greenland, where the Advent message has, under God’s blessing, just secured a humble foothold, to the torrid regions of Africa, where that continent’s traditional darkness is giving way to the light of truth, we see ample evidence that God is with us.’20

In 1959, a young Adventist who had visited the island recalled that Greenland had previously been ‘a mystical word I had sung from childhood’, but now it was an active mission field.21 Living up to the geographic expansiveness of this favourite hymn was a point of pride for Adventists, while, conversely, falling short of it hurt that pride. Though stereotypically defined as remote, distant, and marginal, Greenland was thus also rhetorically and visually central, prompting discomfort at the thought of leaving it untouched and fuelling a belief that reaching it was part of what it meant to be a successful Christian denomination.

Early efforts to reach Greenland

Adventist curiosity in this mysterious land was at first exercised mainly through assurances that other Christian groups were already fulfilling the missionary calling on the island, though without the full delivery of the ‘advent hope’. From the 1860s, the missionary work carried out in Greenland by a different Protestant group, the Moravian Brethren, was a subject of interest to Adventist writers, whose admiration for the intrepid Brethren only grew with time. In January 1881, the Review and Herald began a multi-part glowing profile of their work among the Greenlanders,22 while an article in The Bible Echo in 1900 extolled the determination of the Moravians in converting this supposedly ‘stupid’ people.23

Other times, this interest came from a need to validate the group’s peculiar practices surrounding the Sabbath. When the Adventists made the shift in 1855 from marking the beginning of the Sabbath at 6pm on Friday to marking it at ‘sunset’ on Friday, some concerns were raised that this was too vague and potentially not practicable in areas of the world that experienced little to no sunlight during the winter months and no sunset during the summer months. Multiple Adventists leaders pointed out that the Moravians in Greenland had no trouble identifying when their own Sabbath day (Sunday) began, and so it should be no more difficult for Adventists to know when Saturday should begin.24

Pieces such as these allowed the Adventist readership to participate vicariously in reaching a people about whom they had heard so much, although they did not convince all concerned that they should actually embark for Greenland. In September 1864, James White, president of the Review and Herald Publishing Association and co-founder of the Seventh-day Adventists, admonished what he perceived to be a premature desire to reach beyond the group’s immediate surroundings: ‘Some of you would sooner donate for a mission to China or Greenland, without the least hope of success, than to help support ministers in our own land who are yearly turning hundreds to the truth.’25

If the sending of human missionaries felt at this stage to be an overreach, the next best thing was to send literature. When exactly Adventists started doing this is difficult to pin down. In February 1887, one Adventist periodical claimed: ‘Quantities [of books] have been sent to almost every inhabited part of the globe where the English, French, German, or Scandinavian language is spoken, to Africa, Asia, South America, Iceland, Greenland, and, in fact, to every country where readers can be found.’26 This assertion may simply be a result of confusion stemming from the fact that Greenland was typically grouped with Iceland in Adventist mission reporting. For instance, $250 was allocated by Adventist authorities for work in ‘Iceland and Greenland’ in July-December 1892,27 but this sum was probably intended solely for Iceland.

Later comments by high-ranking Adventists support the conclusion that literature had not yet been sent to Greenland. Ole Andres Olsen, the Swedish president of the General Conference, commented in 1897: ‘Greenland is a country which we should enter with our literature. The inhabitants are largely of Danish origin, and would no doubt be glad to read our tracts and papers in this language.’28 This was still a territory that should be entered, not one that had been entered. Olsen’s erroneous observation that the Greenlanders were ‘largely’ Danish is also indicative of a continued reliance on second- or third-hand information.

Responsibility for evangelism in Greenland was allocated to the newly-created Scandinavian Union Conference (SUC) under the supervision of the European General Conference in 1901.29 Several regional and sub-regional bodies would inherit this responsibility in the decades to come, most notably the Northern European Division. Due to the Protestant faith and advanced economic development of most of this region, a representative of the SUC argued in the Review and Herald that ‘no other field in Europe is more promising than this’.30 The SUC continued the tradition of listing ‘Iceland (with Greenland)’ as a single mission field,31 and it sought to raise enough funds in tithes and offerings to ‘carry the missions in Finland and Iceland and Greenland’.32 Guy Dail of the SUC reported in 1904 that Finland and Iceland had been entered, but not Greenland.33

Some progress was made in 1905 when it was reported that ‘a large package of papers was sent to Greenland’ — probably the first of its kind — and that one Scandinavian missionary student had been talking about ‘entering that field’.34 In June, president P. A. Hansen announced that the SUC was ‘planning to open a mission in Greenland’.35 Across the Atlantic, one J. E. Anderson from the state of Kansas had apparently been working towards entering Greenland himself, but his enquiries into the matter uncovered a problem, this being ‘that the Danish government and church authorities forbid any missionaries landing in Greenland save those of the Lutheran Church’. The General Conference Committee advised Anderson in February 1907 ‘to turn his attention elsewhere’.36 That is where the issue lay for the next few decades.

Ludwig R. Conradi, a leading Adventist in Europe, vaguely referred in 1926 to ‘Sabbath keepers from Greenland and Iceland’, but this is again most likely a result of the conflation of the two nations into one mission field. In 1930, Gustav E. Nord, then president of the SUC, was still referring with urgency to ‘the 14,000 Eskimos of Greenland, to whom this message must be carried. Up to now practically nothing has been done, yet time is hastening on. The arctic as well as the tropics must hear the warning message.’37 Nord’s frustration with the lack of progress in Greenland was echoed in 1932 by Lewis H. Christian, president of the Northern European Division headquartered in London, who complained:

In our world-wide mission work we hear much about the tropics, but very little is said of the lands of the icy north. Yet God loves the Eskimo in Greenland and the Laplanders of Northern Europe and Asia as much as the Bantu races of the south. We have neglected these northern lands. They are far away. They are hard to reach. The people are poor and uneducated, and many of them are nomads, but the advent message is to go to them as well as to other peoples.38

Nineteen-thirty-three marked the first direct contact between Adventists and Greenlanders. The context was a fishing expedition from the Faroe Islands to Greenland’s western coast. As reported in December 1933 in the Review and Herald by J. J. Strahle of the Northern European Division:

Some of our men from the Faroe Islands took some literature with them on a fishing cruise along the coasts of Greenland. The word now comes that some of this literature fell into the hands of the son of a Danish pastor. This young man has become greatly interested in it, and has had much of it translated, mimeographed, and sent out to the Eskimos. This means that another language area has been entered and another country pioneered. Our brethren from the Faroe Islands will be going back to Greenland shortly, and they are planning not only to take literature with them, but also to take a colporteur to canvass while they are there.39

(A mimeograph is a mechanism for cheaply copying documents, while a colporteur is a person who sells and distributes literature.)

This story was very widely distributed as a proof of Adventism’s God-fueled progress, including in the British Missionary Worker magazine.40 Some retellings added or changed small details. For instance, a follow-up article in the Review and Herald in January 1934 specified that the literature was sold, as per the usual Adventist practice, and that the return trip would take place ‘next summer’, i.e., the summer of 1934. The article rejoiced over ‘the providence that has planted the first leaven of the message in that land of which we have so long sung’.41

In March 1935, Louis Muderspach, president of the West Nordic Union Conference, confirmed that the second trip had indeed taken place in 1934 and explained that it met with fascinating results, including the recruitment of a local ‘helper’:

They have taken literature to the important cities on the west coast of Greenland and sent a box containing papers and tracts to “Sukkertoppen” [Maniitsoq] where 800 people are living. A man by the name of Pavia in Faeringahavn [Kangerluarsoruseq] is our best helper. His brother owns a passenger and freight boat which plies along the coast line and he distributes our literature wherever he goes. Most of the Eskimos understand and read Danish, but some articles from our papers have been translated into the Eskimo language and are being used in young people’s societies and other places. The literature distributed includes a wide range of publications. Mr. Pavia promised to translate some of these in the Eskimo language.42

At the 1936 General Conference in San Francisco it was announced by the European representatives that one Faroese Adventist fisherman was making ‘frequent visits up to the coast of Greenland’, and moreover that the aforementioned son of a Danish Lutheran priest had translated ‘a large share of one of our books by Sister [Ellen] White into the Eskimo language’, shining a light in the ‘darkened north’.43 The president of the East Danish Conference related in 1953 that although these fishermen were ‘forbidden to speak to Eskimos’, some of them had managed to befriend a local man named Amon Berthelsen and his son Emil. In a letter to the Conference, Amon sent his ‘dearest and most heartfelt greetings to your church in the Adventist denomination’.44

These forays into Greenland met with great satisfaction in international missionary circles, where it was celebrated that ‘we work in very cold countries as well as in some of the hottest’,45 but there was a lingering sense that selling books was not enough. Louis Halswick, an ambitious missionary who spent much of his life bringing the Seventh-day Adventist message to immigrant and refugee populations in North America,46 wrote in 1944: ‘A few times we have heard of fishermen taking our literature to the Eskimos in Labrador and Greenland, but on the whole very little has been done to give the advent message to this race.’47

Another opportunity for arms-length engagement with the people of Greenland came in the 1940s. The Second World War occasioned the arrival of thousands of US service-people to the new Thule Air Base in northern Greenland. Among them were Adventist soldiers and medical personnel,48 some of whom brought Danish-language literature in the hopes of distributing it.49

On 16 July 1952 — during the final year of the Danish Government’s trade and ecclesiastical monopoly over Greenland — the Northern European Division received a letter from a man in Greenland ‘who had completed the Bible Correspondence Course [the introductory Adventist course] and was keeping the [Saturday] Sabbath’.50 A. F. Tarr, president of the Division, told the General Conference in 1952 that while Greenland was among the ‘completely unentered areas’, this man, probably Amon Berthelsen, was keen ‘to unite with the church that keeps the true Sabbath of the Lord’.51

An opportunity to do this was just around the corner. When the new Danish Constitution was ratified on 28 May 1953, one of the most significant changes for Greenland was the removal of the sole right of the Danish Lutheran Church to evangelise and operate churches on the island, an arrangement that, with the exception of the Moravian Brethren’s mission from 1733 to 1900 under the careful observation of the Danish Mission College, had prevented Greenlanders from encountering alternative forms of Christianity. Soon they would be inundated with an assortment of missionaries who carried in their hearts and minds a small sample of the astonishing multiplicity of modern Christianity.

Advent of the Adventists

Adventists lost no time in taking advantage of Greenland’s opening. The instigating factor was a man named Andreas Nielsen, a Danish Adventist pastor and former Lutheran then serving in the Faroe Islands. Nielsen had been exchanging letters with Amon and Emil Berthelsen in Greenland since 1952.52 Having people ‘on the inside’ ensured that Nielsen was well-informed about constitutional developments and advantageously positioned to exploit them.

On 16 June 1953, Nielsen departed from Copenhagen for a two-month missionary expedition to Greenland aboard the ocean liner Dronning Alexandrine, taking with him sacks full of Adventist books in Danish, including children’s books and magazines. He also had with him four thousand copies of the tract Survival Through Faith translated into Kalaallisut/Greenlandic.53 He landed in Godhavn/Qeqertarsuaq and then travelled to Holsteinsborg/Sisimiut, the hometown of the Berthelsens, where he began selling literature. On 2 July he held a public meeting which he claimed was attended by 250 people (out of a local population of around 1,000), and he then held a Sabbath school lesson on 4 July for 10 children.

Of Amon and Emil, Nielsen wrote: ‘Our friends … seem to understand the present truth quite well. They have now decided to observe the [Saturday] Sabbath. I am hoping that the whole family will join our church, but it will take some time before they are ready for baptism.’54

From Sisimiut, Nielsen travelled to Maniitsoq and then Godthåb/Nuuk, holding further public meetings with the aid of an interpreter. Australian Adventist leader Edward B. Rudge remarked at the conclusion of this two-month expedition that ‘a very excellent foundation has been laid’ by Nielsen in Greenland.55 Delegates at the Northern European Division Council in 1953 heard that the Adventist had ‘reached one sixth of the population [of Greenland] with books and tracts’.56

After returning to Europe, Nielsen reflected that he ‘came to realize how important it is for the people [in Greenland] to get our truth-filled literature in their own language’ rather than only in Danish, and it was due to his agitation that the Northern European Division agreed to allocate money from the 1954 Missions Extension fund to further the Greenlandic translation work.57

Nielsen returned to Greenland with a companion, Ernst Hansen, in the summer of 1954, when the two missionaries continued the task of visiting homes up and down the western coast, holding public meetings (now with the aid of stereoscopic slides), and tending to the religious education of the Berthelsens. In Jakobshavn/Ilulissat, a retired Lutheran minister named Peter Rovsing interpreted for them during a meeting attended by around 150 people, although the Lutheran leadership in Nuuk had apparently sent out a telegram warning the local Greenlanders to ignore the Adventists and urging them to keep the Sunday Sabbath.58

During a visit to Egedesminde/Aasiaat to the north, Nielsen’s arrival was preceded by a notice from the Lutheran Church leadership instructing the locals: ‘1. Be careful when he arrives, for he will most likely ask someone to help him in his work. 2. Do not buy the expensive books he will try to sell you. 3. He will distribute some tracts gratis. They, however, will not do you any harm.’ Whatever happened, it implored: ‘be on your guard and do not encourage him’.

Admonitions such as these had limited effect. An Inuit Lutheran catechist who was also chairman of the Aasiaat town council had been eagerly reading Adventist tracts sent to him by Amon Berthelsen, and was excited to learn more from Nielsen in person. Some interested parties were said by Nielsen to have made hundreds of copies of their tracts to share with other members of their communities. At Frederikshåb/Paamiut, Nielsen claimed that 300 of the 600 inhabitants attended a lecture. All the while, a tiny but loyal Adventist core in Greenland was gradually strengthening its commitment. Amon Berthelsen was baptised in the summer of 1954, the first baptismal harvest of the mission to Greenland,59 while Nielsen and his family resolved to establish themselves permanently on the island as soon as possible.60

Following this second summer tour, Nielsen planned to arrive with his family on a permanent basis sometime in 1955.61 The Greenland Mission was formally organised at the council of the Northern European Division in Watford, England, in February 1955,62 and Nielsen arrived in the spring, setting himself up at first in Julianehåb/Qaqortoq and then heading to Nuuk. He was this time equipped with film strips to aid his evangelism — a much-needed spice in an area now also being worked by energetic Pentecostal missionaries.63 A slide projector and a fur coat were gifted him by Adventists in Iceland.64

Division president A. F. Tarr visited Nielsen in Nuuk later in 1955, bringing with him some clothing supplies for charitable purposes and inspecting the plot on which a combined chapel, charity storehouse, and health clinic was to be built. Tarr was heartened to see that the Berthelsens remained faithful and were even beginning to win over some family members, but somewhat disheartened to see that a teacher from Aasiaat who had been engaged in translating Adventist literature was now refusing to do so, seemingly under Church pressure. Another potentially discouraging interaction was had in the home of a Lutheran Church minister who told Tarr and Nielsen that the main barrier to Greenlanders becoming Adventists would be the fact that the group’s dietary restrictions ruled out the vast majority of Inuit staples.65

In 1956, with reference to his hundreds of home visits and public engagements, Tarr described Nielsen as ‘the best-known personality’ in Greenland.66 This is certainly an exaggeration, but there can be no doubt that he had become remarkably recognisable in only a few short years. His profile was raised even further by his participation in a debate with a Lutheran minister in Nuuk, intended by the minister to ‘expose the fallacies’ of Adventism. After this well-attended disputation, Nielsen was invited to deliver a radio address in Danish which was also then translated into Greenlandic. A relative of his Lutheran interlocutor was supposedly baptised as an Adventist shortly afterwards.67

Nielsen participated in further public disputations with Lutheran leaders in 1957, with the main points of theological controversy being baptism (i.e., whether it was acceptable for children to be baptised, as practiced by the Lutherans) and the proper day for the Sabbath (i.e., Saturday or Sunday). Outside the realms of ‘high theology’, one of Nielsen’s most pressing social concerns was to address the prevalence of alcohol in Greenlandic society. He cooperated with local non-Adventist temperance campaigns to carry forward the doctrine of abstinence.68

Nielsen claimed during his public appearances that the Lutherans and Adventists ultimately wanted the same thing and should therefore work to help each other, but he apparently also compared Lutheran baptisms to counterfeit bank notes, or at least said something that could be so construed. Holger Balle, provost of the Lutheran seminary in Nuuk, rejected both premises, writing in a pair of letters to Greenland’s main newspaper that ‘no one can be mistaken that the Adventists on this crucial point [baptism] want exactly the opposite of what we Evangelical Lutheran Christians want’.69 He declared that ‘a “help” like that of the Adventists, who declare the baptism with which we were baptised to be a false baptism, and will persuade us to be rebaptised — we say no thanks to that “help”.’70

The small Adventist community was in need of a headquarters. Plans for the chapel in Nuuk envisioned a modest structure with seating for 83 people, while the attached clinic was to be equipped for specialist physiotherapy and hydrotherapy — the first facility of its kind in Greenland.71 The opportunity to contribute financially to the construction of this facility via the December 1957 Sabbath Offering was advertised globally through central Adventist publications.72 Though it involved only a relatively small building, the project was invested with some pride because it showed that the Adventists had ‘made it’, so to speak, as a truly worldwide movement capable of reaching ‘earth’s remotest bounds’.73 As in so many respects, Greenland’s mental and moral significance dwarfed the size of its population or the material success of missionaries.

With the help of $17,000 allocated to Greenland by the Northern European Division from the December 1957 offerings, the majority of the construction work was finished in 1958. The chapel was dedicated in May 1959 by M. E. Lind, the visiting Sabbath school secretary for the Division, while the clinic began its operations late in 1958, headed by Danish nurse Anna Hogganvik, and was fully opened in February 1959 under the direction of the Skodsborg Sanatorium in Copenhagen.74 The Division assigned two of its nurses to the island.75 One nurse, Ella Praestiin, had already spent the winter of 1957–8 in the country performing home visitations.76

Treatments at the clinic were largely funded by the Danish medical authorities, which also paid for the nurses to work in Queen Ingrid’s Hospital in Nuuk and for their involvement in a government vaccination campaign against tuberculosis in the mid-1960s,77 all of which contributed to a healthy turnover for the clinic. Dietary matters may be one area where local medical officials and Adventist nurses openly disagreed, for by the latter’s reckoning the high rates of disease in Greenland were partly due to non-vegetarian diets.78

The opening of the facility was publicised over the Greenlandic radio waves, and according to Adventist sources it generally met with a positive reception from both medical officials and ordinary Greenlanders.

The new building was also equipped with a storage basement from which clothing and other necessities could be distributed to the needy, much of it being shipped from the Copenhagen Welfare Centre.79 Additional clothing packages were sent from Iceland during the 1960s via the US Air Force, which carried them free of charge,80 and the Ministry of Greenland and the Royal Greenlandic Trade company granted free use of their own haulage channels for Adventist welfare packages.81

Charity was an indispensable part of the Adventist mission strategy. Nielsen believed that the Greenlanders were in most respects ‘hostile’ to the theological and social contents of his religious message, but he also believed that the medical and charitable work of the Adventists was opening ‘doors and hearts’. In keeping with the Adventist principle that one should attend to the physical needs of a person before inundating them with spiritual messages, he was convinced that ‘the welfare work ought to go hand in hand with the preaching of the Gospel in our field’.82

His optimism was widely shared by those not physically involved. Northern Light, an Adventist publication focusing on Northern Europe, envisaged that the distribution of necessities to poor families in the country would cultivate the minds and souls of residents, leading to ‘a harvest of souls one day in Greenland’.83 G. D. King, secretary of the Division, wrote in 1961 that ‘the clinic [in Nuuk], true to the prophetic predictions of our medical ministry, is making friends and influencing people’, including ‘the Medical Director of the State hospital and the State Medical Director’ in Greenland, who were ‘more than favourably impressed’ by the Church’s contributions to the public good.84

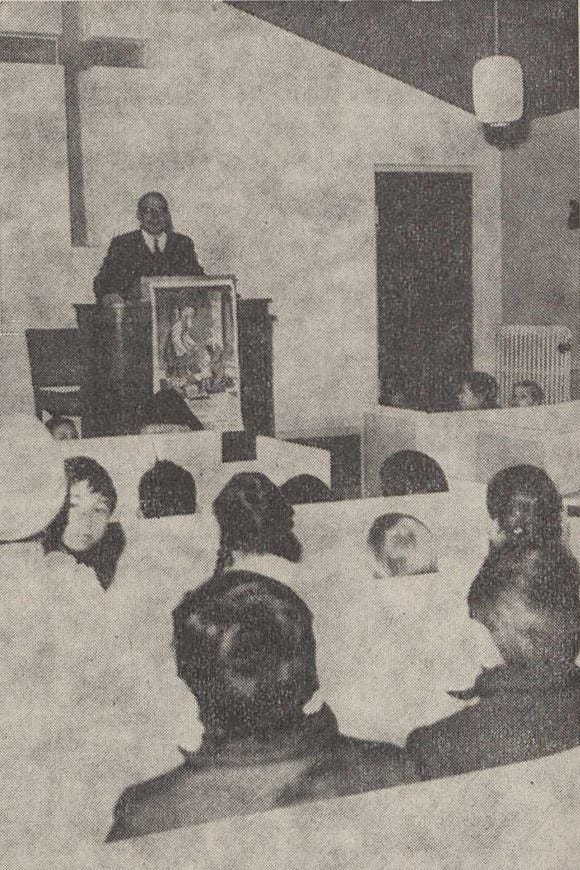

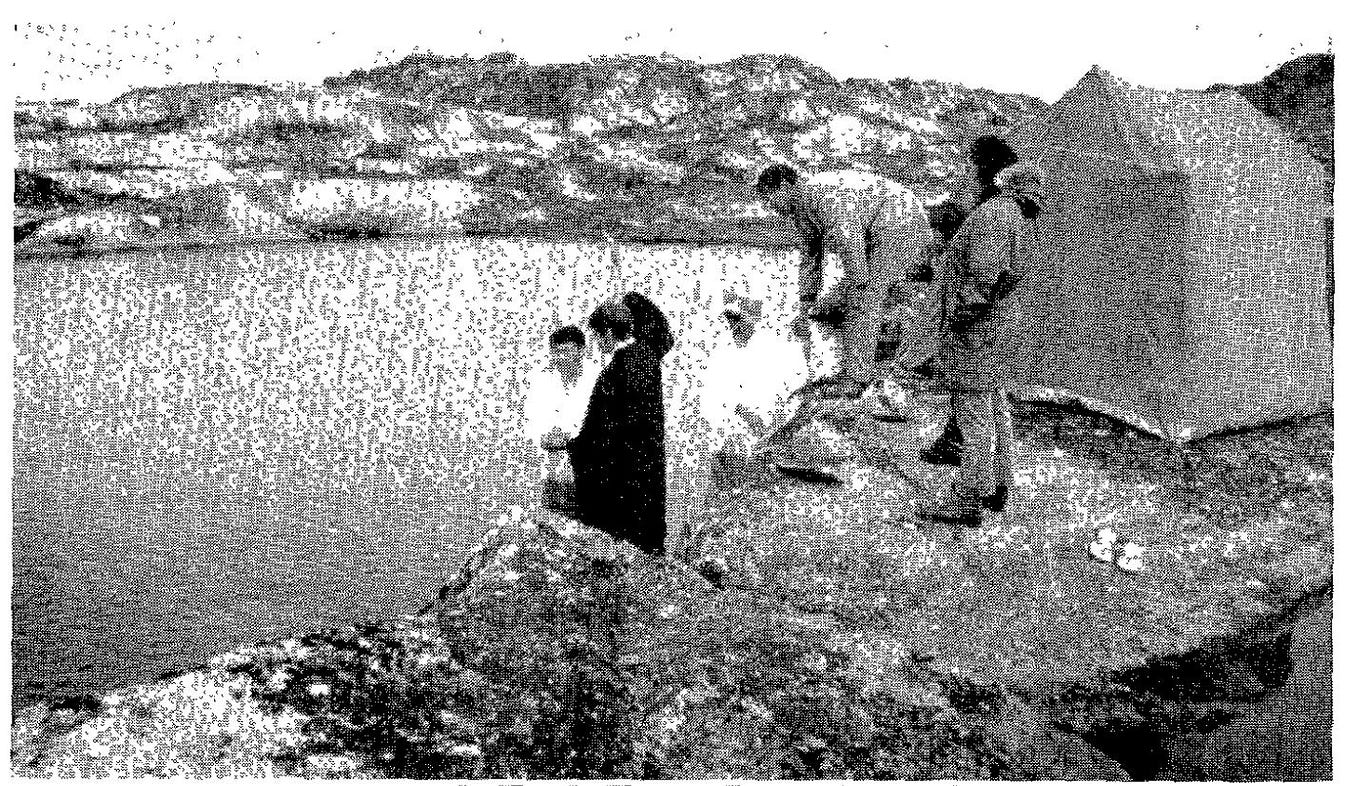

Greenlanders heard and saw a great deal pertaining to the Adventist Church, but very few of them chose to attend chapel services. One typical meeting in the autumn of 1959 drew 21 people.85 The most successful religious offering was the chapel’s Sunday school, which under Nielsen’s successor Jens Arne Hansen was purportedly attended by around 150 children, the vast majority of them, of course, being from non-Adventist families.86 At the same time, baptisms continued to trickle in. The ‘first Eskimo’ to be baptised, a 23-year-old, took the plunge in the summer of 1958,87 and a young married couple was baptised in 1960, followed by a group of four in 1961.

Nielsen and the rest of his ‘growing church’ lobbied the Greenlandic government to allow its members to exercise their freedom from work on Saturday rather than Sunday.88 The year 1961 also saw the first trip by Nielsen into the far-northern part of Greenland — the settlement of Thule/Qaanaaq — where he distributed free clothing, sold tracts, and left behind plastic record players and recordings of lectures for the residents.89 Nearly all significant settlements had now been visited, signalling the conclusion of the initial feverish rush of activity that followed Nielsen’s arrival in 1953.

From the mid-1960s, particularly after Nielsen’s departure in 1963, Adventist life in Greenland settled into a routine of Sabbath observance, medical assistance, charitable work, and the occasional baptism. Attention increasingly turned to the work of serving a tiny existing base of converts and students. In 1968, the Northern European Division purchased a 32-foot fishing boat called the Gunn to enable the Greenland missionaries to travel independently for visitations.90

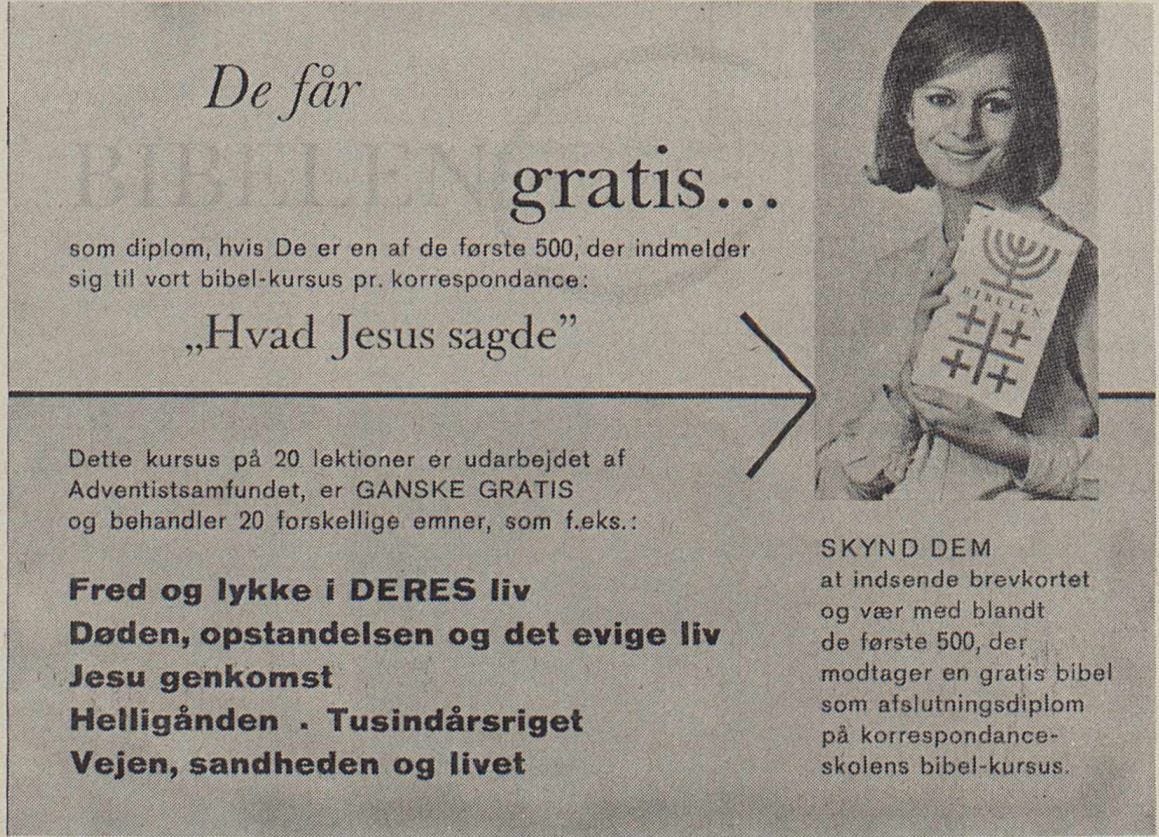

Modest as the actual numbers were, these were heady days. A Danish visitor to Greenland wrote in 1960 that Adventists were ‘without a doubt’ doing ‘the best and most energetic work’ out of the pool of new arrivals.91 In 1971, the chapel placed an advertisement in the bilingual Greenlandic and Danish newspaper Atuagagdliutit / Grønlandsposten for a 20-lesson course covering subjects such as death, the afterlife, Christ’s return, and the ‘Millennium’ (Christ’s thousand-year reign).92 The clinic was modernised and expanded that year, while the Sunday school remained as popular as ever.

In the summer of 1973, the denomination celebrated the baptism of its largest crop of new believers, including six people who were baptised in a single ceremony and a married couple who were baptised in a fjord.93 The congregation celebrated its twentieth anniversary in September 1984 with a special service advertised in Atuagagdliutit, Andreas Nielsen returning to deliver the keynote address.94 As it happened, though, this promising series of events represented the apogee of Adventism’s fortunes in Greenland. Rapid decline followed.

Leaving and returning

One significant blow was delivered in 1990 when the West Nordic Union, the regional body then holding primary responsibility for Greenland, opted not to continue sending paid representatives to serve there. A second blow came soon after in October 1991, when the Greenlandic government terminated its long-standing cooperation with the Adventist clinicians as part of an effort to increase the country’s healthcare independence, abrogating the clinic’s purpose and presaging its dissolution. An unpaid pastor, a KNI (Greenland Trade) employee named Roland Laibjørn, continued to run the chapel until 1998, when the facility that had once captured the imaginations of Adventists across the world was sold. It eventually became Nuuk Art Museum in 2005.95

Individual Saturday Sabbath-keepers persevered during these relatively barren years, though the days of growth were long gone — in 1990 there were 16 reported Adventists living in Greenland, dropping to 13 in 1992. In 2003, the Trans-European Division and the Danish Union initiated steps to re-establish the Greenland mission and undertook exploratory trips to Nuuk, Sisimiut, and Ilulissat to ascertain the viability of an official return to the island. Hopes were dashed when this project was abandoned in 2007, leaving Greenland on the short list of territories classified by the Church as having no ‘established’ Adventist presence.96

Andreas Nielsen’s daughter, Elsebeth Butenko, visited Greenland in 2019 to knock on doors and sell Adventist books, and in 2020 she and her pastor husband secured the agreement of the National Library to stock some of these books in libraries across Greenland. Finally seeing some hope of genuine progress, the Danish Union reopened its enquiries into a full return to Greenland in 2021 in collaboration with Adventist Frontier Missions (AFM).97

A Kenyan couple, Joseph and Beryl Nyamwange, put themselves forward to AFM as volunteer missionaries to Greenland in 2023 and have since then been undergoing preparations to serve there.98 In blog updates on their progress towards that end, Joseph and Beryl tend to lean on phraseology that depicts Greenland as a territory ‘unreached’ by Adventism.99 It is claimed to be a place where no trace of Christ’s ‘remnant movement’ exists, while the Greenlanders themselves, of whom the Nyamwanges wrongly assert ‘89.5 percent … are indigenous Inuits who believe in Shamanism and animism’,100 are said to have ‘not heard … the name of Jesus’.101

During their preparations in Copenhagen in March 2024, the Nyamwanges met a young Dane named Priscilla who had just returned from a seven-week missionary trip to Greenland and who, speaking of ‘miracles’ in her door-to-door and literature evangelism, greatly wished to return.102 In May, they took their first trip to Nuuk to look for a suitable apartment to serve as a mission base, and they visited the Nuuk Art Museum in the former Adventist chapel and clinic.103 They also visited the University of Greenland and met with international exchange students.104

Several components have since fallen into place: A house near central Nuuk was chosen to become the Greenland Mission Facility.105 Joseph and Beryl have secured their visas as non-migrant religious workers, and the process of moving has begun.106 Whether this new effort ‘succeeds’ will depend in no small part on how effectively the Nyamwanges address the failures of the first effort.

Why did Adventism fail in Greenland?

At a glance, the Seventh-day Adventists looked to be the best-positioned of all the newcomers to Greenland after 1953. Members of the Adventist Church had been talking about going to Greenland for almost a century; the first package of literature was sent half a century before; and since the 1930s Faroese Adventist fishermen had enjoyed fairly regular face-to-face contact with residents of the island. When Andreas Nielsen landed in 1953, there was already a father-and-son pair, Amos and Emil Berthelsen, enthusiastically waiting to be taught and baptised. Within just five years, the Adventist chapel and clinic was built, its physiotherapy and Sunday school offerings being very popular with non-Adventist families.

A better start is difficult to imagine. However, what little momentum the nascent congregation had gathered in the actual conversion of Greenlanders was mostly lost by the mid-1970s. The newspaper Atuagagdliutit reassured Lutheran readers that while it may seem that the Church was being ‘torn to pieces’ by the new denominations, ‘the Greenlanders who have been won over to a foreign religious community and as a result have left the national church can be counted on one hand. So no need to panic!’107 Nielsen himself acknowledged following one of his many return visits in 1972 that the ‘visible results’ of all the travelling, preaching, and medical evangelism had been ‘small until now, judged by human standards’.108 He was compelled by further years of stagnation to write more or less the same thing in 1979.109

If one were to make an assessment based on the recurring motifs in the Adventist sources, the most obvious explanation for the absence of a real breakthrough would be the inhospitable nature of the mission field in question. Reports from and about Greenland in the Adventist press during this period of zealous proselytising performed a curious balancing act between two emotive modes. On the one hand, Greenland was described by Adventist authorities as a hostile place due to ‘very low’ moral standards and rampant, unpunished criminality — the type of place where stones would be hurled at missionaries, as purportedly happened to Nielsen.110

The mission was depicted as being persecuted at every turn by a Lutheran establishment bent on guarding its functional monopoly over the ecclesiastical loyalties of Greenland’s citizens. The British Advent Messenger noted in 1954 that the ‘highest civil authorities in the island, the governor as well as the chief of police in Godthaab, and others, were most friendly and helpful’, whereas the firmest opposition ‘came largely from a few of the Lutheran church ministers’, who ‘made it very difficult in a few places to hire halls for meetings, and to secure interpreters’.111

Stories of perseverance in the face of powerful opposition served to lionise Nielsen and the other missionaries as intrepid soldiers of the Truth, and, in a sense, as living martyrs whose sacrifices evoked the celebrated determination of Christianity’s early pioneers.

On the other hand, the reader of these reports cannot avoid the impression that Seventh-day Adventism could never have found a foothold in Greenland without the assistance and warmth of several Lutheran clerics. It was a Lutheran minister, after all, who translated some of the core Adventist texts, including Steps to Christ and The Great Controversy, into Greenlandic in the late 1950s and early 1960s.112 When questioned in 1963 by the Atuagagdliutit newspaper during its investigation into allegations of ‘religious persecution in Greenland’, Andreas Nielsen characterised the early controversies as mere ‘misunderstandings’, assuring the paper that most of the ‘prejudice’ had since been ‘broken down’.113

Narratives that privilege examples of inter-denominational conflict also fail to account for the many friendly interactions between the Adventists and the other new arrivals to Greenland’s religious marketplace. Reporting on his visit to Nielsen in Greenland in 1962, Danish Adventist leader Roland Unnersten recalled a meeting with a Catholic priest in Greenland, Michael Wolfe, who was then overseeing the construction of the Roman Church’s new facility in Nuuk:

We also spent a very interesting hour in the home of a Catholic priest. He lived alone in an American army tent quite a distance from other dwellings. When I asked him how long he intended to stay and work in Greenland, he answered: “For life.” His reply impressed me very much, and made me think that our service also should be for life. This good priest already had Questions on Doctrine in his possession, which he had found very interesting and educational, and now he was considering buying The Great Controversy. We trust that one day he will be among those Catholics who, Sister White says, will in the last days accept the truth.114

Placed alongside the various challenges confronted by Adventism’s evangelists in Greenland, hostility from religious competitors was of comparatively slight consequence.

We saw earlier that a local Lutheran priest told the Adventists that their preference for vegetarianism would be a major obstacle for the widespread acceptance of their spiritual message. There is likely some truth in this, as Greenland’s culinary traditions revolve around the foodstuffs readily available in the area: meat and fish. How to ‘survive’ in Greenland as a vegetarian or vegan tourist in the twenty-first century is a subject that multiple travel blogs have tried to address, usually with some difficulty.115 Adventist dietary teachings are simply not practicable for most residents, and in any case would entail the abandonment of deep cultural traditions.

Another dietary regulation promoted by the Adventists is abstinence from alcohol. In an October 1986 address, president of the Trans-European Division and future president of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists Jan Paulsen pointed to cultural incompatibility around alcohol as a reason for the stagnation of the mission: ‘Adventism’s total abstinence from alcoholic beverages runs against the grain in this society where drinking is part of the way of life. Because of the high rate of alcoholism and related problems, Greenland needs the message that Adventists have to share.’116

This claim is harder to evaluate. Telling people to abandon a favourite pastime is certainly a cause of friction, but alcoholism is not unique to Greenland, nor is abstinence and temperance a foreign concept to Greenlanders. As mentioned earlier, Andreas Nielsen worked alongside homegrown temperance movements. One denomination that preaches temperance (though not abstinence), the Jehovah’s Witnesses, met with slightly more success, which could indicate that the nucleus of the ‘answer’ to the failure of Adventism in Greenland lies elsewhere. The strategies employed by the Witnesses deserve some consideration.

Unlike the Adventists, the Jehovah’s Witnesses imported Danish families to increase its numbers at key junctures, ensuring that it always had at least a small pool of regular congregants and new young people to baptise. The number of Witness ‘publishers’ (literature evangelists) in Greenland has never fallen below 60 since the early 1970s, and never below 100 since the late 1980s. This also greatly improved the group’s visibility across the island, as there were Witness families in most major settlements who could perform evangelistic activities without the need for the leaders in Nuuk to undergo constant travel. Most Witnesses in Greenland are Danish, and yet the existence of a substantial Witness community means that there is still the possibility of a breakthrough among Inuit Greenlanders.

Rhetorically, the Witnesses never tried to make themselves appear more ‘normal’ by claiming that they and the established Lutheran Church wanted the same thing. They are unapologetically distinct, or ‘weird’ — a reputation which the Adventists actively tried to avoid — putting clear conceptual mileage between themselves and the status quo and making for a more convincing case as to why a person might want to leave the ubiquitous Lutheran community.

Finally, with its larger resident congregation, the Witness mission did not depend financially on an inherently high-turnover operation like a physiotherapy unit. Its finances and its place in the public consciousness could not be hobbled by a single decision like the 1991 termination of government ties with the Adventist clinic.

Taken together, these factors help explain the differing fortunes of the two apocalyptic sects, with fate granting one of them a settled place in the Greenlandic religious ecosystem and relegating the other to failure. As for the fortunes of the new Adventist mission: Watch this space.

Notes

- J. Brunt, ‘The Great Disappointment and the hope of the Advent yet to come’, Adventist Education, vol. 57, 1995, pp. 5–9. https://www.andrews.edu/library/car/cardigital/Periodicals/Journal_of_Adventist_Education/1994/jae199457010505.pdf ↩︎

- Seventh-day Adventist Church, ‘Death, the state of the dead, and resurrection’, as of 23 September 2024. https://www.adventist.org/death-and-resurrection/ ↩︎

- Seventh-day Adventist Church, ‘What Adventists believe about the Sabbath’, as of 23 September 2024. https://www.adventist.org/the-sabbath/ ↩︎

- A. Awaludin, Jamal, and Muttaqin, ‘The doctrine of Seventh-day Adventist Church on food according to Ellen G. White’, Kalimah: Jurnal Studi Agama Dan Pemikiran Islam, vol. 16, no. 1, 2018, pp. 51–70. https://doi.org/10.21111/klm.v16i1.2513 ↩︎

- M. Brunt, ‘The ten: Countries or areas with no Adventists’, Adventist Record, 28 March 2019. https://record.adventistchurch.com/2019/03/28/the-ten-countries-or-areas-with-no-adventists/ ↩︎

- ‘The last witness’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 15, no. 20, 5 April 1860, p. 153. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH18600405-V15-20.pdf ↩︎

- ‘To correspondents’, The Health Reformer, vol. 1, nos. 11–12, June 1867, p. 184. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/HR/HR18670601-V01-11,12.pdf ; D. M. Canright, ‘“Unequally yoked together”’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 37, no. 22, 16 May 1871, p. 173. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH18710516-V37-22.pdf ↩︎

- G. W. A., ‘Read and profit’, The Health Reformer, vol. 2, no. 5, November 1867, p. 73. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/HR/HR18671101-V02-05.pdf ↩︎

- ‘The Esquimaux of Alaska’, The Health Reformer, vol. 12, no. 11, November 1877, p. 334. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/HR/HR18771101-V12-11.pdf ↩︎

- Good Health, vol. 23, no. 6, June 1888, p. 231. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/HR/HR18880601-V23-06.pdf ↩︎

- ‘The bone-bag’, The Youth’s Instructor, vol. 38, no. 7, 12 February 1890, p. 28. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/YI/YI18900212-V38-07.pdf ↩︎

- P. Spickard, ‘Shape shifting: Toward a theory of racial change’, Genealogy, vol. 6, no. 2, 2022, p. 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy6020048 ; A. S. Post, Olof Krarer, the Esquimaux lady: A story of her native home (Ottawa, IL: Press of W. Osmon & Sons, 1887). ↩︎

- ‘A wonderful visitor’, The Youth’s Instructor, vol. 38, no. 38, 17 September 1890, p. 150. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/YI/YI18900917-V38-38.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Domestic life in Greenland’, The Youth’s Instructor, vol. 38, no. 19, 7 May 1890, pp. 73–4. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/YI/YI18900507-V38-19.pdf ↩︎

- A. T. Robinson, ‘The Beatrice (Neb.) camp-meeting’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 83, no. 37, 13 September 1906, p. 17. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19060913-V83-37.pdf ↩︎

- B. E. Beddoe, ‘Into all the world’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 101, no. 36, 18 September 1924, p. 6. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/ARAI/ARAI19240918-V101-38.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Review of our unentered countries — no. 3’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 91, no. 6, 5 February 1914, p. 8. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19140205-V91-06.pdf ↩︎

- H. L. Rudy, ‘Greenland entered by full-time missionary’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 131, no. 61, 30 December 1954, p. 24. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19541230-V131-61.pdf ↩︎

- W. R. Beach, ‘Into all the world’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 132, no. 42, 20 October 1955, p. 12. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19551020-V132-42.pdf ↩︎

- ‘A message to the Advent people’, British Advent Messenger, vol. 61, no. 26, 21 December 1956, p. 1. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/BAM/BAM19561221-V61-26.pdf ↩︎

- M. H. Morrill, ‘Greenland interlude’, The Youth’s Instructor, vol. 107, no. 31, 4 August 1959, p. 13. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/YI/YI19590804-V107-31.pdf ↩︎

- M. L. H., ‘The Moravian mission to Greenland’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 57, no. 2, 11 January 1881, pp. 28–9. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH18810111-V57-02.pdf ↩︎

- ‘The gospel in Greenland’, The Bible Echo, vol. 15, no. 3, 15 January 1900, p. 53. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/BEST/BEST19000115-V15-03.pdf ↩︎

- J. Clarke, ‘The Sabbath law’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 20, no. 18, 8 September 1862, p. 144. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH18620930-V20-18.pdf ; J. N. Loughborough, ‘The Sabbath on a round world’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 24, no. 20, 11 October 1864, p. 158. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH18640412-V24-20.pdf ; ‘Abbott on the Sabbath’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 54, no. 2, 3 July 1879, p. 10. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH18790703-V54-02.pdf ↩︎

- J. White, ‘The “Vision of a Poor Mortal”’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 24, no. 18, 27 September 1864, p. 141. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH18640329-V24-18.pdf ↩︎

- ‘The late General Conference’, Bible Echo and Signs of the Times, vol. 2, no. 2, February 1887, p. 25. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/BEST/BEST18870201-V02-02.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Missionary appropriations’, Home Missionary Extra, September 1892, p. 3. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/HM/HM18920901-V04-09e.pdf ↩︎

- O. A. Olsen, ‘President’s address’, General Conference Daily Bulletin, vol. 1, no. 8, 23 February 1897, p. 121. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/GCSessionBulletins/GCB1897-D08.pdf ↩︎

- ‘The European General Conference’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 78, no. 36, 3 September 1901, p. 576. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19010903-V78-36.pdf ; General Conference Session Recording Minutes, 21 April 1901, p. 65. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Minutes/GCSM/1901/GCRS19010421.pdf ↩︎

- L. R. Conradi, ‘The Scandinavian Union Conference’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 79, no. 11, 18 March 1902, p. 171. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19020318-V79-11.pdf ↩︎

- G. Dail, ‘The first year of the European General Conference: Statistical report’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 80, no. 8, 24 February 1903, pp. 13–14. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19030224-V80-08.pdf ↩︎

- G. Dail, ‘The Scandinavian Union and Swedish meetings’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 80, no. 36, 10 September 1903, pp. 9–10. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19030910-V80-36.pdf ↩︎

- G. Dail, ‘Scandinavian Union Meeting’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 81, no. 37, 15 September 1904, p. 13. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19040915-V81-37.pdf ↩︎

- ‘News and notes’, The Educational Messenger, vol. 1, no. 7, 1 April 1905, p. 11. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/EM/EM19050401-V01-07.pdf ↩︎

- P. A. Hansen, ‘Scandinavian Union Conference’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 82, no. 23, 8 June 1905, p. 12. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19050608-V82-23.pdf ↩︎

- Minutes of the 143rd meeting of the General Conference Committee, 4 February 1907, p. 335. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Minutes/GCC/GCC1907.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Cheering words from northern Europe’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 107, no. 29, 6 June 1930, p. 128. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19300606-V107-29.pdf ↩︎

- L. H. Christian, ‘In the Arctic North’, Missions Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 4, Fourth Quarter 1932, p. 4. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/MissionsQtrly/MQ19321001-V21-04.pdf ↩︎

- J. J. Strahle, ‘Another country entered’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 110, no. 49, 7 December 1933, p. 24. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19331207-V110-49.pdf ↩︎

- ‘An inspiring council’, The Missionary Worker, vol. 38, no. 25, 15 December 1933, p. 2. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/MW/MW19331215-V38-25.pdf ↩︎

- W. A. Spicer, ‘Along “Greenland’s icy mountains”’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 111, no. 3, 18 January 1934, p. 24. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19340118-V111-03.pdf ↩︎

- L. Muderspach, ‘The West Nordic Union’, The Advent Survey, vol. 7, no. 3, March 1935, p. 4. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/TASNED/TASNED19350301-V07-03.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Proceedings of the General Conference’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 113, no. 31, 8 June 1936, p. 196. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19360608-V113-31.pdf ↩︎

- ‘The Advent message in Greenland’, Northern Light, vol. 3, no. 9, September 1953, p. 1. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19530901-V03-09.pdf ↩︎

- ‘The great needs of our missions in northern Europe’, Mission Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 4, Fourth Quarter 1937, p. 39. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/MissionsQtrly/MQ19371001-V26-04.pdf ↩︎

- W. Wells, ‘Seventh-day Adventist mission to immigrants from 1920–1965: An exploration of immigration trends, laws, and the church’s missional response’, Journal of Adventist Mission Studies, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 89–111. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/jams/vol19/iss2/10/ ↩︎

- L. Halswick, ‘Call of the north’, Australasian Record, vol. 48, no. 18, 1 May 1944, p. 6. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/AAR/AAR19440501-V48-18.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Our servicemen’, Southern Tidings, vol. 37, no. 25, 28 June 1944, p. 8. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/SUW/SUW19440628-V38-25.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Adventist doctor in Greenland’, Australasian Record, vol. 50, no. 46, 18 November 1946, p. 8. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/AAR/AAR19461118-V50-46.pdf ↩︎

- ‘What impressed Dr. Murdoch most’, Australasian Record, vol. 56, no. 50, 15 December 1952, p. 3. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/AAR/AAR19521215-V56-50.pdf ↩︎

- ‘The Autumn Council of the General Conference’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 129, no. 41, 9 October 1952, p. 8. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19521009-V129-41.pdf ↩︎

- H. Muderspach, ‘First missionary visit to Greenland’, Australasian Record, vol. 57, no. 44, 2 November 1953, p. 13. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/AAR/AAR19531102-V57-44.pdf ↩︎

- E. B. Rudge, ‘Greenland entered!’, Australasian Record, vol. 57, no. 28, 13 July 1953, p. 13. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/AAR/AAR19530713-V57-28.pdf ↩︎

- ‘The Advent message in Greenland’, Northern Light, vol. 3, no. 9, September 1953, p. 1. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19530901-V03-09.pdf ↩︎

- E. B. Rudge, ‘Pioneer work in Greenland’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 130, no. 42, 15 October 1953, p. 32. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19531015-V130-42.pdf ↩︎

- R. R. Figuhr, ‘Northern European Division Council’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 130, no. 53, 31 December 1953, p. 14. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19531231-V130-53.pdf ↩︎

- A. Nielsen, ‘Greenlandic Literature’, British Advent Messenger, vol. 59, no. 6, 19 March 1954, pp. 5–6. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/BAM/BAM19540319-V59-06.pdf ↩︎

- E. B. Rudge, ‘Good news from Greenland’, Northern Light, vol. 4, no. 9, September 1954, p. 7. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19540901-V04-09.pdf ↩︎

- ‘A message from Pastor E. E. Roenfelt’, Northern Light, vol. 4, no. 10, October 1954, p. 2. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19541001-V04-10.pdf ↩︎

- A. Nielsen, ‘From Greenland’s icy mountains’, Northern Light, vol. 4, no. 12, December 1954, pp. 1–2. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19541201-V04-12.pdf ↩︎

- A. Nielsen, ‘From Greenland’s icy mountains, part 2’, Northern Light, vol. 5, no. 1, January 1955, pp. 15–16. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19550101-V05-01.pdf ↩︎

- H. L. Rudy, ‘Three division councils meet in Europe’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 132, no. 7, 17 February 1955, p. 22. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19550217-V132-07.pdf ↩︎

- A. Nielsen, ‘Greenland’, Northern Light, vol. 5, no. 8, August 1955, p. 3. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19550801-V05-08.pdf ↩︎

- J. Gudmundsson, ‘Progress in Iceland’, Northern Light, vol. 5, no. 3, March 1955, pp. 3–4. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19550301-V05-03.pdf ↩︎

- A. F. Tarr, ‘Under the northern lights’, Northern Light, vol. 5, no. 12, December 1955, pp. 1–3. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19551201-V05-12.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Autumn council convenes’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 133, no. 46, 15 November 1956, p. 7. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19561115-V133-46.pdf ↩︎

- A. F. Tarr, ‘From Scandinavia to Ethiopia’, British Advent Messenger, vol. 62, no. 23, 15 November 1957, p. 10. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/BAM/BAM19571115-V62-23.pdf ↩︎

- A. Nielsen, ‘Growth in Greenland’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 135, no. 1, 2 January 1958, p. 21–3. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19580102-V135-01.pdf ↩︎

- H. Balle, ‘Læserbreve og klip’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 97, no. 5, 14 March 1957, p. 10. https://timarit.is/page/3779066 ↩︎

- H. Balle, ‘Læserbreve og klip’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 97, no. 7, 11 April 1957, p. 10. https://timarit.is/page/3779112 ↩︎

- A. Nielsen, ‘Physiotherapy clinic in Greenland’, Northern Light, vol. 9, no. 4, April 1959, pp. 1–2. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19590401-V09-04.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Thirteenth Sabbath offering’, Sabbath School Lesson Quarterly, Fourth Quarter 1957, p. 47. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/SSQ/SS19571001-04.pdf ; A. F. Tarr, ‘Surveying the needs of the Northern European Division’, Missions Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 4, Fourth Quarter 1957, p. 3. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/MissionsQtrly/MQ19571001-V46-04.pdf ; A. Nielsen, ‘Greenland — the world’s largest island — is calling’, Missions Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 4, Fourth Quarter 1957, pp. 19–20. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/MissionsQtrly/MQ19571001-V46-04.pdf ↩︎

- J. M. Bucy, ‘New gallery fellowship day’, Northern Light, vol. 8, no. 1, January 1958, p. 1. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19580101-V08-01.pdf ↩︎

- A. F. Tarr, ‘From Greenland’s icy mountains’, The Inter-American Division Messenger, vol. 36, no. 9, September 1959, p. 7. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/IAM/IAM19590901-V36-09.pdf ↩︎

- V. G. Anderson, ‘Northern European Division Winter Council’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 136, no. 1, 1 January 1959, p. 23. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19590101-V136-01.pdf ↩︎

- C. L. Torrey, ‘Million dollar offering’, Northern Light, vol. 8, no. 9, September 1958, p. 6. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19580901-V08-09.pdf ↩︎

- A. Lohne, ‘Mid Greenland’s icy mountains’, Signs of the Times, vol. 91, no. 11, November 1964, pp. 10–11, 31. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/ST/ST19641101-V91-11.pdf ↩︎

- M. Tabler, ‘Interview with missionary from Greenland’, Atlantic Union Gleaner, vol. 65, no. 8, 21 February 1966, p. 4. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/ALUG/ALUG19660221-V65-08.pdf ↩︎

- T. Kristensen, ‘Copenhagen Welfare Centre’, Northern Light, vol. 11, no. 4, April 1961, p. 7. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19610401-V11-04.pdf ↩︎

- R. Burgess, ‘Gifts for Greenland’, Northern Light, vol. 16, no. 11, November 1966, p. 3. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19661101-V16-11.pdf ↩︎

- A. Nielsen, ‘Filantropi og kristendom’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 101, no. 14, 29 June 1961, p. 23. https://timarit.is/page/3782316 ↩︎

- A. Nielsen, ‘The kind hands of Dorcas’, Northern Light, vol. 10, no. 1, January 1960, p. 3. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19600101-V10-01.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Greenland news’, Northern Light, vol. 11, no. 2, February 1961, p. 7. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19610201-V11-02.pdf ↩︎

- G. D. King, ‘Greetings from Greenland’, Northern Light, vol. 11, no. 7, July 1961, pp. 1–2. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19610701-V11-07.pdf ↩︎

- A. Nielsen, ‘Greenland’, Northern Light, vol. 9, no. 10, October 1959, p. 8. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19591001-V09-10.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Forkynder evangeliet for at fremskynde dommedag’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 107, no. 8, 13 April 1967, p. 6. https://timarit.is/page/3787041 ↩︎

- T. Lucas, ‘Missionary Volunteer Department’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 135, no. 35, 10 July 1958, p. 221. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19580710-V135-35.pdf ↩︎

- A. Nielsen, ‘Greenland’s growing church’, Northern Light, vol. 11, no. 7, July 1961, p. 2. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19610701-V11-07.pdf ↩︎

- A. Nielsen, ‘From Godthåb to Thule’, Northern Light, vol. 12, no. 4, April 1962, pp. 2–3, 7. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19620401-V12-04.pdf ↩︎

- V. Cooper, ‘Northern European Division’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 145, no. 35, 29 August 1968, p. 15. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19680829-V145-35.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Citater — til eftertanke’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 111, no. 16, 5 August 1971, p. 24. https://timarit.is/page/3790855 ↩︎

- ‘De får Bibelen gratis…’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 111, no. 7, 1 April 1971, p. 28. https://timarit.is/page/3790522 ↩︎

- O. Bakke, ‘Greenland: Taking the gospel to ice-bound Eskimos’, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 150, no. 44, 1 November 1973, pp. 17–18. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19731101-V150-44.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Alle er hjertelig velkommen’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 124, no. 39, 26 September 1984, p. 62. https://timarit.is/page/3812994 ↩︎

- Nuuk Art Museum, ‘About Nuuk Art Museum’, as of 21 September 2024. https://www.nuukkunstmuseum.com/en/nuuk-art-museum/ ↩︎

- N. Johansson, S. H. Jensen, and J. E. Pedersen, ‘Greenland mission’, Encyclopedia of Seventh-day Adventists, 26 January 2021. https://encyclopedia.adventist.org/article?id=CCS5#fn19 ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- ‘Joseph & Berly Nyamwange’, Adventist Frontier Missions, as of 23 September 2024. https://afmonline.org/missionaries/detail/8801 ↩︎

- J. Nyamwange and B. Nyamwange, ‘Our call to the coolest place on earth’, Adventist Frontier Missions, 1 September 2023. https://afmonline.org/post/our-call-to-the-coolest-place-on-earth ↩︎

- J. Nyamwange and B. Nyamwange, ‘God’s humor in our call’, Adventist Frontier Missions, 1 October 2023. https://afmonline.org/post/gods-humor-in-our-call ↩︎

- J. Nyamwange and B. Nyamwange, ‘Inspired misunderstandings’, Adventist Frontier Missions, 1 November 2023. https://afmonline.org/post/inspired-misunderstandings ↩︎

- J. Nyamwange and B. Nyamwange, ‘The joy of meeting fellow sojourners’, Adventist Frontier Missions, 1 March 2024. https://afmonline.org/post/the-joy-of-meeting-fellow-sojourners ↩︎

- J. Nyamwange and B. Nyamwange, ‘Angels’, Adventist Frontier Missions, 1 June 2024. https://afmonline.org/post/angels ↩︎

- J. Nyamwange and B. Nyamwange, ‘Learning to study’, Adventist Frontier Missions, 1 July 2024. https://afmonline.org/post/learning-to-study ↩︎

- J. Nyamwange and B. Nyamwange, ‘A shelter in the time of storm’, Adventist Frontier Missions, 1 August 2024. https://afmonline.org/post/a-shelter-in-the-time-of-storm ↩︎

- J. Nyamwange and B. Nyamwange, ‘The Lord is at work, we see’, Adventist Frontier Missions, 1 September 2024. https://afmonline.org/post/the-lord-is-at-work-we-see ↩︎

- ‘»Så gør vi så’en, når til kirke vi gå«’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 15, 19 July 1962, p. 16. https://timarit.is/page/3783100 ↩︎

- A. Nielsen, ‘From Greenland’s icy mountains’, World Mission Report, vol. 62, no. 3, Third Quarter 1972, pp. 19–21. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/MissionsQtrly/MQ19730701-V62-03.pdf ↩︎

- A. Nielsen, ‘God’s work advances in Greenland’, Adventi Review and Sabbath Herald, vol. 157, no. 45, 2 October 1980, p. 16. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH19801002-V157-45.pdf ↩︎

- H. Westerlund, ‘A visit to Greenland’, Northern Light, vol. 10, no. 9, September 1960, pp. 10–12. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19600901-V10-09.pdf ↩︎

- G. A. Lindsay, ‘Literature for Greenland’, British Advent Messenger, vol. 59, no. 4, 19 February 1954, p. 2. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/BAM/BAM19540219-V59-04.pdf ↩︎

- J. M. Bucy, ‘Greenland’s greetings’, Canadian Union Messenger, vol. 28, no. 1, 7 January 1959, p. 2. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/CUM/CUM19590107-V28-01.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Religionsforfølgelse i Grønland?’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 103, no. 14, 4 July 1963, p. 13. https://timarit.is/page/3783849 ↩︎

- R. Unnersten, ‘News from Greenland’, Northern Light, vol. 13, no. 3, March 1963, pp. 3–4. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NL/NL19630301-V13-03.pdf ↩︎

- N. Zosia, ‘How to survive as a vegetarian on Greenland’, Sleepless in Kirchberg, 9 July 2016. https://sleeplessinkirchberg.wordpress.com/2016/07/09/how-to-survive-as-a-vegetarian-on-greenland/ ; Mel, ‘How to survive as a vegan on Greenland’, Northtrotter, 28 February 2019. https://northtrotter.com/2019/02/28/how-to-survive-as-a-vegan-on-greenland/ ↩︎

- J. Paulsen, ‘Trans-Europe — a variety of challenges’, Mission, vol. 75, no. 4, Fourth Quarter 1986, p. 5. https://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/MissionsQtrly/MQ19861001-V75-04.pdf ↩︎

3 responses to “Seventh-day Adventists in Greenland”

[…] many Christians (e.g., the Seventh-day Adventists), some Bahá’ís in the early twentieth century found themselves drawn to Greenland by Reginald […]

LikeLike

[…] many of the newcomers to Greenland’s religious scene like the Seventh-day Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses were commonly excluded from ecumenical (cross-denominational) […]

LikeLike

[…] Greenland when the Lutheran ecclesiastical monopoly was abolished in 1953 – including Catholics, Adventists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Bahá’ís – the Pentecostal movement was one of the few that the […]

LikeLike