Two Jehovah’s Witnesses with literature on a cart suited for the ice and snow, Sisimiut, Greenland. Posted to Facebook by a Jehovah’s Witness community, 10 December 2019.

- Establishing the mission

- Film and other media

- Conflict with the Lutheran Church

- ‘Reaching the farthest corners of the world’

- Gathering momentum

- The effect of the Witnesses on the Lutheran community

- Into the 21st century

- Notes

Jehovah’s Witnesses are an apocalyptic, puritan, and non-Trinitarian Christian denomination that originated in the Bible Student movement of the United States in the 1870s and 1880s. The organisation orbits around its flagship publication, The Watchtower, a magazine focusing on Bible study and global mission issued by The Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society (est. 1881). Watch Tower founder Charles Taze Russell predicted in his dispensationalist text Three Worlds, and the Harvest of This World (1877) that the ‘times of the Gentiles’, i.e., the final age before the return of Christ, would ‘end in A. D. 1914’, at which point the Day of the Wrath of the Lord would occur and Jesus would begin his thousand-year reign on Earth.1

After 1914, the emphasis shifted to accommodate the fact that there were no obvious signs of such a change. The official line on the timing of the end gradually loosened, with the Watch Tower leadership contending that the generations alive in 1914 would live to see the end of days and that 1914 marked the invisible beginning of Christ’s kingship.2 The informal label ‘Jehovah’s witnesses’ was adopted by Watch Tower members in 1931, deriving from Isaiah 43:10 in the Old Testament, ‘“You are my witnesses”, declares the Lord’, or as it is presented in the New World Translation favoured by members of this sect, ‘“You are my witnesses,” declares Jehovah.’ The group believes that it is important to use God’s name when calling upon him. ‘Jehovah’ comes from a Germanised version of Yahweh, which is itself an approximation of the pronunciation of the Hebrew name for God in Exodus 6:3: ‘YHWH’. Witnesses do not believe in the Holy Trinity, and they do not regard Jesus as God.3

Jehovah’s Witnesses are most commonly encountered in town centres, gathered beside a cart or stand at which one can engage in conversation and take beginner-level Watch Tower Society literature.

Establishing the mission

Measured by continuous presence, the Jehovah’s Witnesses are the second-oldest religious organisation in Greenland behind only the Danish Evangelical-Lutheran Church. The Seventh-day Adventists were the first to take advantage of the abolition of the Lutheran Church’s ecclesiastical monopoly over Greenland in 1953, but they were left with no official presence after 1998 when their chapel in Nuuk was sold.4

Sometime in 1953 or 1954, one Watch Tower member served informally in Greenland as a ‘publisher’, i.e., a member who spreads the organisation’s literature and performs outreach work,5 but the mission officially got underway when two Witnesses named Kristen Lauritsen and Arne Hjelm arrived in Greenland’s capital city Godthåb/Nuuk in January 1955. They soon began a thousand-mile trip up and down the western coast, living mainly in tents, guesthouses, and sometimes the homes of sympathetic locals.6 They were equipped with a selection of the Watch Tower’s literature in Danish and could even offer one pamphlet, This Good News of the Kingdom, in Kalaallisut/Greenlandic.

In the 1956 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses, the missionaries described a mixed reception from both Danes and Inuit, although they reported that for the most part the Inuit Greenlanders acted ‘in accord with their happy, carefree, friendly and hospitable nature. They were glad to see [the missionaries] and anxious to ask questions.’ Groups of up to twenty Greenlanders are said to have visited them late at night to enquire of their message — supposedly to avoid embarrassment.

Some members of the Danish elite were ‘surprised and often upset’ at their presence, but the yearbook reports over the next few decades consistently identified the Lutheran priests as the most energetic opponents. The 1956 report cites one instance of a priest leveraging his influence to have the missionaries evicted from their accommodation.7 At least a few Inuit Greenlanders were angry with the Danish authorities for having ‘let Jehovah’s Witnesses into the country’.8 Unlike the Catholic Church, which gradually gained the acceptance of Greenlanders between the 1950s and the 1970s, the Jehovah’s Witnesses never ceased being contentious.

Film and other media

Missionaries from the Watch Tower were early adopters of visual media formats as tools in evangelism. If the stereotypical mode of encountering Jehovah’s Witnesses is now the knock on the door, for much of the world in the 1950s it was arguably public viewings of movies shown via portable projector kits.

Released in 1954, The New World Society in Action is a 70-plus minute narrated documentary film detailing the inner workings of the Watch Tower, including its printing operations, Bible studies, and the lives of its members. The film features many impressive shots of urban and natural environments, some of them aerial shots and some in full colour. The first Witnesses in Greenland possessed the equipment to show the picture, and for many people, especially those living in difficult-to-reach settlements, The New World Society would have been their first exposure to colour film.

Despite entrenched ‘clergy opposition’, the 1957 yearbook report enthusiastically notes that ‘nearly 1,600’ people had seen the film — more than 1 out of every 20 Greenlanders — and that it was being ‘talked about from one end of Greenland to the other’. Scenes depicting full-immersion baptisms performed on adults apparently caused some puzzlement, since the Greenlanders were more accustomed to the Lutheran style of sprinkling water on babies.9 In 1957, the Greenland mission received a second film titled The Happiness of the New World Society for which narration in the Greenlandic language was recorded.10

Even if their doctrinal message could sometimes be unintelligible to unfamiliar audiences, the films were highly effective as novelties and conversation-starters. As the bilingual Greenlandic/Danish newspaper Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten asked rhetorically in 1962: ‘Who doesn’t want to see a movie when it’s in colour and it’s free?’ It judged that ‘the movie itself was bland’, but the chance to see a series of beautiful shots of cities, trains, planes, industrial machinery, and other symbols of modernity was enough to retain a curious viewership.11

The films were sometimes shown in care homes for the elderly, and in one such home the missionaries exclaimed that even ‘opposers’ were ‘much more friendly to the truth’ after the screening.12

In a retrospective piece, the 1993 yearbook cites the ’dean of Greenland’ as saying in the 1950s or 1960s: ‘Jehovah’s Witnesses are the most aggressive [of the new denominations in Greenland]. They are rushing up and down the coast showing this film about the glories of the Millennium. And these colorful pictures do make an impression.’13 A healthy 590 people reportedly attended showings of another new film in 1964 — though we do not know how the count was done or whether the reported figures include those who attended for only a short time.14 By April 1963, concern with the apparent success of the films in Denmark caused the Lutheran Church to plan its own film ‘about the sect Jehovah’s Witnesses’. Local Lutheran leaders promised that they would ‘try to get it to Greenland’ if it was financially viable. Atuagagdliutit welcomed the Church’s intention to take down this ‘satanic sect’ using its own favoured medium.15

One of the ‘lower-tech’ formats employed by Jehovah’s Witnesses at this time was theatrical performances of Bible stories, used especially as set-pieces at mission conferences. Due to the limited materials available to make sets and the lack of sufficient numbers of believers to perform, missionaries in places like Greenland and the Faeroe Islands could not replicate this method, but from the early 1970s a workaround was developed: Complex sets of Bible locations would be built in countries with larger Witness communities and costumed actors would pose for a series of still colour slides. These slides were sent to missionaries in more remote places, along with an audio recording of the dialogue and background noises. The slides would then be projected and manually changed to follow the audio.16 In this way, the Witnesses in Greenland were enabled to further expand their repertoire of media offerings, far outstripping anything the other churches had at their disposal.

However, while they themselves relied heavily on modern technologies to complement their work, the missionaries repeatedly warned that the rapid pace of change in Greenlandic industry and entertainment was sullying the morality of the Greenlanders. In 1961 they wrote: ‘Recently some of the features of modern materialism have begun to flood the land, and this occupies their attention. It is not unusual to have to hold a sermon amidst the noise of the radio or phonograph music with the latest records being played.’17 A similar comment was made in 1967: ‘Great changes are taking place on Greenland as a result of bringing in industry. One bad effect is that moral standards are getting worse.’18

Conflict with the Lutheran Church

The Jehovah’s Witnesses succeeded very gradually in securing a hearing among a few members of the other churches.19 They set up Bible study groups and, though they had no converts as yet, they did befriend some young Greenlanders. One of these supposedly began reading Witness literature to hospital patients, but was subsequently warned by his Lutheran priest that he would be ‘cut off from all sacraments’ if he became too embroiled in the sect. The priest also said the ‘new world Jehovah’s witnesses tell about will never come’.20

Stories of inhospitable Lutheran clergy appear many times in the yearbook reports. In one instance from the 1961 report, a priest is said to have told some young men who had been attending lessons with the Witnesses that they would be ‘outcasts from society if they continued’.21 In 1966, a priest referred to the Witnesses as a ‘small insignificant sect’ to some visiting Americans.22 And in 1969, the missionaries complained that a priest was refusing to sell Bibles to them.23

It is difficult to determine how many of these reported sayings were ever truly spoken and how many are exaggerated or decontextualised to serve the narrative purposes of the newcomers. A bit of both is likely. Some Lutherans believed that this ‘priest-eating sect’ harboured pure disdain for the established Church, being prone to ‘violent outbursts against its leaders’, so to some extent Lutheran hostility was framed as retaliation.24

The use of the Germanic name for God, ‘Jehovah’, was one of the central points of contention between the Witnesses and the Lutherans, and according to the mission reports a lay priest told them in 1959/60 ‘that the dean over Greenland had given all priests in Greenland written notice to definitely avoid using the name “Jehovah” or “Jahve” in the future’ so as not to lend the Witnesses too much credibility in the eyes of the laity.25 Whether or not the instruction took precisely this form, it is probably a real concern. One Lutheran loyalist publicly urged the priests to ‘be careful not to use phrases that are too similar to those used by Jehovah’s Witnesses’.26

The Lutheran leadership and the writers at Atuagagdliutit (often one and the same people) were not content to let the Witnesses go unchecked; they were at pains to define and condemn the message of these ‘friendly men with folders’; these seemingly harmless people who knock on doors and are ‘impossible to get rid of’ when invited inside. An article from July 1962 called Witness beliefs ‘so false and unchristian that it would be a great, great calamity should they succeed in recruiting even half a dozen members from among the Greenlandic population’. The new era of ‘religious freedom’ meant they had every right to be in Greenland, but the article noted with satisfaction that ‘Jehovah’s Witnesses have now worked for 8–9 years in Greenland without having recruited a single follower among the Greenlandic population’.27

The newspaper campaign against the Witness creed stepped up a gear later that month when the Church began a seven-part series in its dedicated page of Atuagagdliutit titled ‘Jehovas Vidner — Bibelsk Hedenskab’ (‘Jehovah’s Witnesses — Biblical Heathenism’). The first article sought to dismantle the logic behind the use of the name ‘Jehovah’ for God, arguing that since the vowels are missing in the Hebrew ‘YHWH’, and since ‘Jehovah’ is a result of multiple layers of translation, ‘Yahweh’ is the best pronunciation of God’s name. The article combatively concluded that ‘it must be very embarrassing for [Witnesses] that it has been discovered that the word “Jehovah” is a misunderstanding’.28

Witness missionary Mogen Voss hit back in August with an article outlining his own biblical evidence for the correctness of ‘Jehovah’ and for other doctrines.29 In another piece at the end of September, Voss pointed out that the Danish missionary Otto Fabricius had himself used the name ‘Jehovah’ in his Greenlandic translation of the Book of Genesis in 1822.30

Marking the end of the ‘Biblical Heathenism’ series in November, a representative of the Church signed off with an overarching repudiation of a perceived self-centredness of the Witness doctrine of immortal glorification for the faithful few: ‘The teachings of Jehovah’s Witnesses will give self-assurance instead of hope and lead people away from love back to self-love and away from freedom back to slavery and fear.’31 Voss continued to respond in the newspaper to letters from ordinary Greenlanders expressing doubts and concerns about his organisation,32 insisting that the eschatology of the group ‘is a great message of joy’.33

‘Reaching the farthest corners of the world’

In January 1963, Voss provided an intriguing rationale and vindication of the presence of the missionaries in the sparsely-populated place: ‘Along with these things, the gospel of the Kingdom was to be preached everywhere. Regardless of one’s view of Jehovah’s witnesses, one must admit that they preach the kingdom of God as the only hope for mankind, and that their message is rapidly reaching the farthest corners of the world.’34

Voss is here referring to the Great Commission — the final instructions given by Jesus before his Ascension. As variously reported in the New Testament (quoted here from the Watch Tower’s own New World Translation), Jesus ordered the faithful to ‘make disciples of people of all the nations’ (Matthew 28:19) and to ‘be witnesses of me in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the most distant part of the earth’ (Acts 1:8). He is also alluding to Jesus’s words concerning the timing of the end of the present ‘system of things’ in Matthew 24:14: ‘And this good news of the Kingdom will be preached in all the inhabited earth for a witness to all the nations, and then the end will come.’ As interpreted by Jehovah’s Witnesses, this verse makes the global distribution of the ‘good news of the Kingdom’ a precondition for (or sign of) the end of days.

Having a presence in Greenland performs a mission-affirming and morale-boosting function for the Jehovah’s Witnesses. To preach and teach in Greenland became a mark of honour, as the very fact of being there, especially in the small settlements nestled within the fjords of the Arctic Circle, is believed to signal a loyalty to the Commissioner — an unbreakable urge to reach those nations that feel farthest from the beaten path. For members of any church that has made this leap, stories of the Gospel working among the Greenlanders is proof positive of progress in the propagation of the faith in all corners.

To this effect, a 1991 article in The Watchtower specifically posited that Greenland fits the bill as ‘the most distant part of the Earth’ mentioned in Acts 1:8.35 Another article from 1996 drew attention to missionary work in the far-northern settlement of Qaanaaq, then known as Thule. The article said that Thule’s etymology harkened back to a word used ‘since ancient times to describe an ultimate goal, geographic or otherwise’, and it noted that by evangelising in this place the Witnesses had ‘literally reached distant parts of the earth, at least in the northerly direction’, thus ‘carrying out their Master’s injunction’.36

Gathering momentum

Whereas the hot-tempered public disputations between the Lutherans and the Catholic Church in Greenland had largely receded by the early 1970s, the Jehovah’s Witnesses continued to attract the opprobrium of Lutheran priests, who believed it was necessary to warn the ‘new generation’ about the ‘conceptual confusion and delusion’ allegedly propagated by the Witnesses.37 However, the mission entered the 1970s with a new sense of momentum.

In the 1969–70 service year several Danish Witness families moved to Greenland ‘to serve where the need is great’,38 and in 1971 the mission reported its first baptism of a Greenlander — a young woman from the north who had previously sought spiritual truth in the Lutheran, Pentecostal, and Adventist churches. After several impactful encounters with Witness missionaries in Nuuk, she ‘ceased all actual association with the State Church’, and was baptised in Denmark in July 1971.39 The first baptism of a Greenlander in Greenland took place in 1973.40

Nineteen-seventy-three also marked a different milestone — the beginning of the translation of each issue of The Watchtower magazine into Greenlandic, carried out at the Nuuk Kingdom Hall (a Kingdom Hall is the Witness equivalent of a church/chapel).41 The mission held its first congress in Nuuk in August 1972, attended by 70 Witnesses based in the country (most of them migrants from Denmark) and 91 short-term Danish visitors.42 The next congress in 1976 was attended by 90 participants from Greenland and 60 from Denmark.43

A news report on the 1979 congress highlights the geographical spread achieved by the Witnesses, with representatives from congregations in seven cities and towns which together form an arc that bends from the middle of the western coast to its end in the south, containing a firm majority of Greenland’s population.44 This arc begins at Ilulissat to the north, descending southward through Aasiaat, Sisimiut, Maniitsoq, Nuuk, and Paamiut, and terminating on the southern tip of the island at Qaqortoq. By and large, the Witness population consisted of families from Denmark.

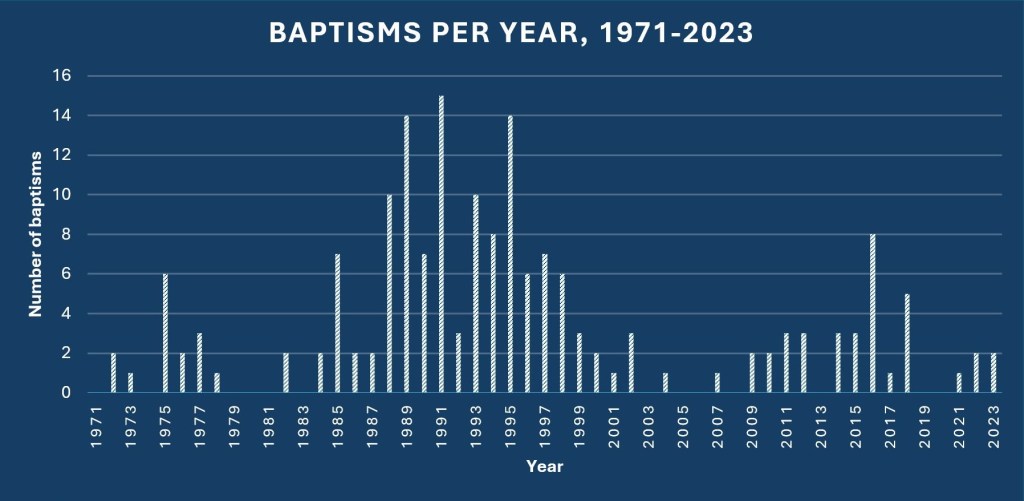

The years from 1985 to 1998 represent the ‘golden age’ of Jehovah’s Witness conversion in Greenland. Throughout the history of the mission in Greenland, the number of baptisms per year has typically ranged from 0 to 3, whereas they ranged from 6 to 15 during the years in question. Baptism statistics include those born into Danish Witness families in Greenland, but does not include baptisms of Greenlanders in Denmark or elsewhere. The numbers of converted Greenlanders were finally sufficient to send out an Inuit-led missionary expedition into northern Greenland in 1990.45 Most of the converts were young people who encountered considerable cultural friction in their efforts to live out Witness stipulations around alcohol and the proper preparation of meat-foods (similar to Kosher dietary rules).46

Atuagagdliutit took particular notice of a wave of baptisms in 1989 and 1990, and also reported that by 1990 there were 120 active members and 80 non-Witnesses who regularly attended services at Greenland’s Kingdom Halls. Ulrik Møller, Lutheran pastor of the Hans Egede Church in Nuuk, told the paper that congregants who departed to the Witnesses would always be welcome back. However, Gudrun Chemnitz, the head of the congregational council in the city, admitted that she ‘usually gets angry when someone moves to Jehovah’s Witnesses from the Christian church’ — an anger aimed less at the new recruits and more at the organisation itself, which ‘attracts people by using the Bible as a weapon’.47

The effect of the Witnesses on the Lutheran community

In 1990, Christian Tidemand, a Lutheran priest in Ilulissat, furiously claimed that the Witnesses primarily went after ‘psychologically impressionable’ and ‘mentally susceptible’ people who were led to believe ‘that their mental problems are due to demonic possession, which only the Jehovah’s exorcist method can treat’. But the fact that any at all were willing to jump ship to the Kingdom Halls spoke to a deep ‘spiritual void’ in contemporary Greenland, proving that the Church was not doing enough to look after the elderly and address the epidemic of loneliness then taking hold. It was the responsibility of Lutheran leaders to ensure that people did not have to resort to joining the Witnesses to fulfil their social and spiritual needs. ‘In short,’ Tidemand concluded, ‘in word and deed we must point to God as the possibility of love.’48

The Lutherans were being shown up in too many areas by a denomination renowned for its explosive energy. In Tidemand’s own town, Ilulissat, the Witnesses self-built an expanded facility in 1991,49 a task they completed in just two weeks.50 A whole new Kingdom Hall was built in Nuuk during the 1994 service year with the help of 80 Witnesses from Denmark.51 By contrast, the old Church was starting to look tired, unimaginative, and ineffective — an impression that loyalists observed with both discomfort and a resolution to meet the challenge head-on.

Just as the Lutheran Church in the 1960s employed Greenlandic artists to beautify its churches so as to avoid an unfavourable contrast with the incoming Catholic Church, the arrival of the Jehovah’s Witnesses seemed to ask for a renewed urgency in Lutheran pastoral activities. The Pentecostal missionary Rune Åsblom urged the priests of the established Church: ‘We need to help people stop alcohol abuse here in Greenland, and you yourself must be a role model in this regard, also for all the other clergy in Greenland.’52

Into the 21st century

The Witnesses had managed in the space of a few decades to entrench themselves in all of Greenland’s major population centres and become a regular feature of the island’s news cycle, but their momentum has dissipated considerably in the twenty-first century. This is reflected mainly in baptism numbers, which remain stagnant in the low single digits (at best), and in the reduction in the number of congregations from 7 to 6 in 2008,53 and then down to 5 in 2017.54 The ratio of publishers to citizens in the country peaked at 1 to 331 in 2017 (see graph below) but this was achieved mainly through migration rather than conversion.

There have, however, been a few landmark advancements. Since the missionaries first arrived, one very major component in their work had been missing: A translation of the New World Bible into Greenlandic. The Watchtower had been available in Greenlandic since 1973, and the companion magazine Awake! from 1992,55 while by 2013 the local translation team included Inuit Greenlanders,56 but the movement had depended on other groups’ Bible texts that did not reflect their unique theological and eschatological concerns. Non-Witnesses in Greenland also took notice of this absence. Atuagagdliutit reported in 1985 on a completed Watch Tower translation of the Bible into Danish, and noted: ‘Naturally, one would also like to have a translation into Greenlandic, but the fulfilment of this wish lies in the distant future.’57

Finally, in October 2021, a full New Testament translation into Greenlandic was completed by the Watch Tower following two years of work by three translators.58

The Jehovah’s Witnesses are now the only non-Lutheran denomination with their own substantial Greenlandic translation of scriptures. This may or may not signal the beginning of a new ‘golden age’. On the one hand, a push by the Jehovah’s Witnesses into the far northern reaches of Canada in recent years signals a refusal to give up on the region.59 Moreover, the fact that the Greenlanders continue to show interest in church affiliation in the midst of a secularising world could play to the Watch Tower’s favour. According to the 2022 US Department of State ‘Report on International Religious Freedom: Denmark’, 93% of Greenlanders are members of the Church of Greenland, a largely autonomous branch of the Danish Church set up as part of Greenland’s move towards national independence.60 On the other hand, this means that the vast majority of converts to other religious groups will have to be convinced to leave their national Church — a task in which the Witnesses have only enjoyed modest success.

Another challenge for missionaries is the perception among Inuit Greenlanders that Jehovah’s Witnesses are ‘a religion for Danish people’.61 The Witnesses began a new initiative to promote Greenlandic language skills among their Danish members in 2009.62 Visibility is one factor that consistently plays to their advantage. In 2016, they held a conference at the Katuaq cultural centre in Nuuk which drew around 700 members from across the North Atlantic,63 one of the largest religious gatherings in a single location ever to take place in Greenland, but visibility does not automatically translate into conversions. The overwhelming emphasis in the national Greenlandic media is still on the behavioural restrictions that being one of Jehovah’s Witnesses imposes, or what a person must give up to be one.64

If current conversion and baptism rates continue, the Witnesses will keep their status as a ‘minnow’ in Greenland’s religious culture, albeit one of the largest minnows. A visit to the organisation’s website will tell you that there are currently 119 ‘ministers who teach the Bible’ (members involved in outreach) in the country.65 The government-funded Trap Greenland encyclopaedia estimates there to be around 150 Witnesses currently active.66

Notes

- C. T. Russell, Three worlds, and the harvest of this world (Rochester, NY: N. H. Barbour, 1877), pp. 83, 155, 157–8. ↩︎

- A. Holden, Jehovah’s Witnesses: Portrait of a contemporary religious movement (London: Routledge, 2002), pp. 19–20. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 24. ↩︎

- N. Johansson, S. H. Jensen, and J. E. Pedersen, ‘Greenland mission’, Encyclopedia of Seventh-Day Adventists, 26 January 2021. https://encyclopedia.adventist.org/article?id=CCS5&highlight=greenland ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1955 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1955), p. 133. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1993 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1993), pp. 115–18. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1956 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1956), pp. 129–30. ↩︎

- H. Lynge, ‘Grønlands-kvad og et svar-kvad’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 99, no. 8, 23 April 1959, p. 14. https://timarit.is/page/3780563 ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1957 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1957), p. 131. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1993 Yearbook, p. 119. ↩︎

- J. Lind, ‘Farvefilm’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 7, 29 March 1962, p. 17. https://timarit.is/page/3782862 ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1962 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1962), p. 124. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1993 Yearbook, p. 119. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1965 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1965), p. 103. ↩︎

- ‘Jehova filmen’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 103, no. 8, 10 April 1963, p. 19. https://timarit.is/page/3783667 ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 125–6. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1961 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1961), p. 122. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1967 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1967), p. 130. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1958 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1958), p. 144. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1959 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1959), p. 142. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1961 Yearbook, p. 122. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1966 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1966), p. 114. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1969 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1969), p. 122. ↩︎

- ‘Hvorfor skyde med kanoner?’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 103, no. 11, 22 May 1963, p. 19. https://timarit.is/page/3783764 ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1960 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1960), p. 127. ↩︎

- ‘Børns optagelse i menigheden’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 103, no. 15, 18 July 1963, p. 12. https://timarit.is/page/3783877 ↩︎

- ‘Venlige mænd med mapper’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 14, 6 July 1962, p. 20. https://timarit.is/page/3783076 ↩︎

- ‘Jehovas Vidner — bibelsk hedenskab’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 15, 19 July 1962, p. 16. https://timarit.is/page/3783100 ↩︎

- ‘Jehovas vidners lære’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 18, 30 August 1962, p. 10. https://timarit.is/page/3783174 ↩︎

- ‘Jehovas Vidner — bibelsk kristendom’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 20, 27 September 1962, p. 10. https://timarit.is/page/3783229 ↩︎

- ‘Biblesk hedenskab 7. Slutning’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 23, 8 November 1962, p. 20. https://timarit.is/page/3783333 ↩︎

- ‘Svar til Hans Kanuthsen’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 24, 22 November 1962, p. 10. https://timarit.is/page/3783351 ↩︎

- ‘Jehovas vidner — bibelsk kristendom’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 25, 6 December 1962, p. 12. https://timarit.is/page/3783381 ↩︎

- ‘Jehovas vidner bibelsk kristendom IV’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 103, no. 3, 31 January 1963, p. 10. https://timarit.is/page/3783514 ↩︎

- ‘“To the most distant part of the Earth”’, The Watchtower, 1 January 1991, pp. 5–6. https://jws-library.one/?file=data/1991/w_E_19910101/A+Global+Joy.html ↩︎

- ‘Witnesses to the most distant part of the Earth’, The Watchtower, 15 June 1996, pp. 23–7. https://jws-library.one/?file=data/1996/w_E_19960615/Witnesses+to+the+Most+Distant+Part+of+the+Earth.html ↩︎

- ‘Fup eller fakta? Lad jer ikke forvirre!’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 112, no. 25, 7 December 1972, p. 23. https://timarit.is/page/3792005 ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1970 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1970), p. 140. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1971 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1971), p. 123. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1993 Yearbook, p. 128. ↩︎

- ‘Christian Greek scriptures released in Greenlandic’, JW.org, 4 November 2021. https://www.jw.org/en/news/region/greenland/Christian-Greek-Scriptures-Released-in-Greenlandic/ ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1973 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1973), pp. 11–12. ↩︎

- ‘Kongress’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 116, no. 36, 9 September 1976, p. 22. https://timarit.is/page/3796562 ↩︎

- ‘Jehovas vidner til kongres’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 119, no. 37, 13 September 1979, p. 3. https://timarit.is/page/3801502 ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1993 Yearbook, p. 138. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 139–40. ↩︎

- ‘Ånden blev styrket’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 130, no. 90, 10 August 1990, p. 5. https://timarit.is/page/3826575 ↩︎

- ‘Utroværdige vidner’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 130, no. 138, 28 November 1990, p. 9. https://timarit.is/page/3827466 ↩︎

- ‘»Venner af frihed«’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 131, no. 86, 31 July 1991, p. 3. https://timarit.is/page/3829662 ↩︎

- ‘Hurtigbyg hos Jehovas Vidner’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 131, no. 104, 11 September 1991, p. 8. https://timarit.is/page/3830033 ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1995 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 1995), p. 18. ↩︎

- ‘Bland ikke Pinsemissionen og Jehovas Vidner’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 129, no. 37, 5 April 1989, p. 15. https://timarit.is/page/3822602 ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 2008 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 2008), pp. 33–4. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 2017 Yearbook of Jehovah’s Witnesses (New York: Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society, 2017), pp. 180–1. ↩︎

- Watch Tower Society, 1993 Yearbook, p. 141. ↩︎

- ‘The Greenlandic Watchtower praised on TV’, JW.org, 2013. https://www.jw.org/en/jehovahs-witnesses/activities/publishing/greenlandic-watchtower-magazine/ ↩︎

- ‘Jehovas Vidner præsenterer ny bibeloversættelse’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 125, no. 19, 8 May 1985, p. 11. https://timarit.is/page/3814421 ↩︎

- ‘Christian Greek scriptures released in Greenlandic’, JW.org. https://www.jw.org/en/news/region/greenland/Christian-Greek-Scriptures-Released-in-Greenlandic/ ↩︎

- J. Duin, ‘Jehovah’s Witnesses, Sikhs, Muslims: New religious groups race to Arctic’, Newsweek, 20 November 2022. https://www.newsweek.com/2022/11/25/jehovahs-witnesses-sikhs-muslims-new-religious-groups-race-arctic-1759921.html ↩︎

- United States Office of International Religious Freedom, ‘Report on International Religious Freedom: Denmark’, US Department of State, 2022. https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-report-on-international-religious-freedom/denmark/ ↩︎

- worldofwaedeled, ‘Qaqornoq — village preaching trip’, personal blog, 3 June 2013. https://worldofwaedeled.wordpress.com/2013/06/03/qaqortoq-village-preaching-trip/ ↩︎

- ‘Jehovas Vidner på grønlandskkursus’, Sermitsiaq, 3 August 2009. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/jehovas-vidner-pa-gronlandskkursus/134696 ↩︎

- S. Rasmussen, ‘400 udenlandske deltagere til Jehovas Vidner-stævne i Nuuk’, Sermitsiaq, 9 July 2016. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/400-udenlandske-deltagere-til-jehovas-vidner-staevne-i-nuuk/572142 ↩︎

- ‘Livet som et Jehovas Vidne’, Sermitsiaq, 18 August 2010. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/livet-som-et-jehovas-vidne/142670 ↩︎

- ‘Jehovah’s Witnesses around the world: Greenland’ JW.org, as of 9 September 2024. https://www.jw.org/en/jehovahs-witnesses/worldwide/GL/ ↩︎

- F. A. J. Nielsen, ‘Religion and religious communities’, Trap Greenland, 2021. https://trap.gl/en/kultur/religion-og-trossamfund/ ↩︎