Reconstruction of a Norse house at L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland. Wikimedia Commons.

- Contemporary evidence for an Inuit mission

- Turning to the heathens

- Later references to an Inuit mission

- Vestiges of an unclear past

- Decoding the absence

- Sámi parallels

- Fragments of an answer

- Notes

Around the year 985 CE, Norse settlers established small farming communities on the western coast of Greenland. The main historical source outlining these events is a pair of Icelandic sagas, the Grœnlendinga saga (Saga of the Greenlanders) and Eiríks saga rauða (Saga of Eirik the Red). The first of these claims that the settlers had among their mostly ‘heathen’ ranks a man ‘from the Hebrides, a Christian’, who represented the faith then sweeping into the former ‘pagan’ strongholds of Northern Europe.

Some years later, Leif, the son of the colony’s leader Eirik the Red, executed the command of the Norwegian King Olaf Tryggvason (reigned 995–1000 CE) to fully Christianise the colony. Leif ‘the Lucky’ is also said to have been the first to land in ‘Vínland’, a place somewhere in Eastern Canada (possibly Newfoundland), where the Norse met some of the existing inhabitants of the continent.

Another saga, the Íslendingabók (Saga of the Icelanders), tells of how the Norse discovered that Southern Greenland had also once been occupied by other people: ‘They [the Norse] found signs of human habitation there both in the east and west of the country, fragments of skin-boats and stone implements, from which it may be deduced that the same kind of people had passed through there as had settled Vínland and [whom] the Greenlanders call Skrælingar.’1

The word Skrælingar is commonly thought to refer to the small stature or ‘uncivilised’ state of the encountered people, since in later Danish usage it means ‘weakling’, ‘puny’, or ‘wretched’ , but other theories suggest that it refers to their skin-pelt clothing or their tendency to shout at approaching parties.2 As an ethnonym, the word is imprecise and can apply to any of the non-European cultural groups witnessed by the Norse Greenlanders from the tenth century until they ‘vanished’ around 1500 CE.

In the version of history represented in the sagas, two facts stand out: Christianity was a part of Norse Greenlandic life from the very beginning, and the settlers were cognisant from an early stage that they were not alone in the region. If we combine these observations, we arrive at a tantalising question: Did the Norse settlers or their clergy ever try to convert the so-called Skrælingar to Christianity?

Direct references in the contemporary sources to conversion efforts among the Inuit or other North American groups are rare. The notion of converted Skrælingar appears mostly in a few passing mentions in the Icelandic sagas and annals and a spattering of second-, third-, or fourth-hand accounts in letters sent to or from distant powers in Europe, mostly Church officials. Later European commentaries on the fate of the ‘vanished’ settlers from the eighteenth century onwards speculated that the Norse and the Inuit had merged together to the detriment of the Christian faith, or that, at the culmination of a long collision between incompatible communities of Christians and intransigent pagans, the latter triumphed.

Contemporary evidence for an Inuit mission

Chronologically, the earliest reported instance to the conversion of the Skrælingar comes from Eiríks saga rauða, written down in the thirteenth century, which tells of the journeys to Vínland and the nearby ‘Markland’ made by Norse explorers. During one expedition under the leadership of a man called Karlsefni, they took and baptised two boys who could very well be the first ever Christians from a North American ethnic group:

They had southerly winds and reached Markland, where they met five natives [Skrælinga]. One was bearded, two were women and two of them children. Karlsefni and his men caught the boys but the others escaped and disappeared into the earth. They took the boys with them and taught them their language and had them baptised. They called their mother Vethild and their faither Ovaegi. They said that kings ruled the land of the natives; one of them was called Avaldamon and the other Vildidida. No houses were there, they said, but people slept in caves or holes. They spoke of another land, across from their own. There people dressed in white clothing, shouted loudly and bore poles and waved banners. This people assumed to be the land of the white men.3

Assuming that this saga is a dramatisation of real history, it is worth noting that the two boys from the group of ‘Skrælinga’ are ‘taken’ and acculturated into the Norse community. They do not return to their own people to spread Christianity any further, although it is conceivable, given that some of Karlsefni’s own children married bishops or became bishops themselves,4 that these boys or their descendants could also have attained the status of clergy. In that scenario we would have an example of people who both knew North American languages and had some form of Christian authority. But that remains pure speculation.

Norwegian historian Arnved Nedkvitne places the first known meetings between the Norse and the Inuit in Greenland sometime between ca. 1050 and 1150. The earlier date is derived from the fact that the Íslendingabók’s section on the settlement of Greenland, which describes the discovery of objects formerly belonging to the Inuit, not the Inuit themselves, was based on information from a man who had been in that country at some point in the latter half of the eleventh century. The later date comes from the Historia Norwegie, written around 1150. This is the first text to mention an encounter with living Inuit (along with some fantastical details):

North of the Greenlanders, hunters have come across ‘small men’ (homunciones) whom they call Scrælinga. If they are stung with weapons and survive, their wounds grow white without bleeding, but if the wound is fatal the blood scarcely stops flowing. They are totally without iron and employ walrus teeth as missiles, sharp stones as knives.5

The first signs that the Church might have had an interest in converting the Skrælingar also come from this period. Several of the Icelandic sagas assert that Eirikr Upsi, as bishop of Garðar (the Greenland diocese), ‘journeyed to find Vínland’ in ca. 1121, and Nedkvitne speculates that ‘Eirikr may have felt an obligation to Christianise the skrælingar’.6 Another intriguing possibility is that Eirikr, as the first bishop known to have resided in Greenland, brought with him specific instructions from his superiors to grow the boundaries of Christendom in the Far North.

The Church also seems to have taken the lead in organising expeditions to find out how close Inuit hunting activities were getting to the Norse settlements. The Grænlandsannál (Greenland Annals), written in the seventeenth century but drawing on medieval sources, describes Norse hunters being sent northwards up the West Greenland coast in 1266 and again a year or two later, a project probably directed by the priests.7

When contact between the Church and Vestribygð (the Western Settlement) was lost in the middle of the fourteenth century, it was Ivar Bårdsson, a Church official, who was sent in the early 1340s to find out what had happened. According to a second-hand account, Bårdsson formed the impression that ‘the Skrælings have destroyed all of the Western Settlement’, because he found abandoned houses and livestock but ‘no people either Christian or heathen’8⁸ Bårdsson had previously spent so much time in Greenland that he acquired the moniker ‘the Greenlander’, and given his presumed knowledge of the situation it could be inferred from his report that the Norse and Inuit had been in close contact, possibly of a hostile nature, for a while.

Turning to the heathens

Far from the Inuit being converted, some Christian commentators in Europe believed the exact opposite was happening in this remote corner of Christendom. In 1343, the Skálholt Annals in Iceland supposedly included a note regarding the Christians of Greenland. The original note no longer exists but it was paraphrased by the bishop Gisli Oddsson in the early seventeenth century:

The inhabitants of Greenland of their own free will abandoned the true faith and the Christian religion, having already forsaken all good ways and true virtues, and joined themselves with the folk of America. Some consider too that Greenland lies closely adjacent to the western regions of the world. From this it came about that the Christians gave up their voyaging to Greenland.9

Aside from the obvious anachronism of the word ‘America’, the note could represent a real medieval perception that the faith of the Norse Greenlanders was especially fickle.

In the late-twelfth or early-thirteenth century, an anonymous annotator to Adam of Bremen’s Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontifi cum (Acts of the Bishops of Hamburg), first published in the 1070s, reported that the people of ‘Gótaland, Sweden, [and] Greenland’ would claim only to be ‘in part Christian, even though they are without faith and without confession and without baptism. In part they even worship Jupiter and Mars [probably Odin and Thor], although they are likewise Christian.’10

Reports of an advancing pagan threat in Greenland took on two very different forms in the European Catholic imagination: sometimes the belief was that the Norse had voluntarily left the Christian faith; other times they would be conceived as good Christians who suffered under the constant threat of pagan oppression.

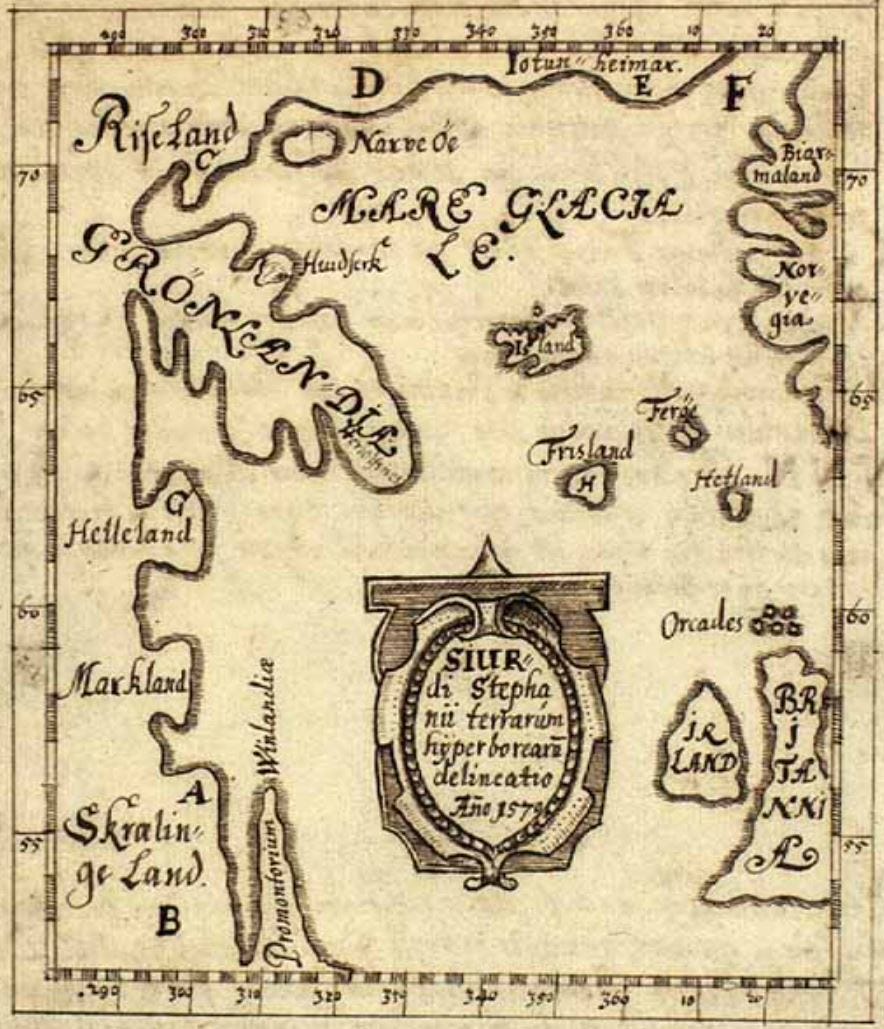

In the late 1420s, the Danish cartographer Claudius Clavus annotated Greenland on one of his maps with the comment that ‘infidel caroli frequently descend upon Greenland in great armies’, apparently confusing the Inuit with the Karelians, another ‘pagan’ group to the east of Scandinavia. A 1448 letter supposedly ordered by Pope Nicholas V also referred to the Greenlanders as being under attack from ‘neighbouring pagan shores’.11

If these attacks were real, their effect on the morale of the settlers would have been greatly elevated by the knowledge that their relationship with the papal authorities, and thus their connection with Christendom, was tense. Multiple papal letters from the late thirteenth century seem to suggest that the people of Vestribygð or perhaps the whole Garðar bishopric were excommunicated.12 When Ivar Bårdsson arrived in Vestribygð in the 1340s with an armed expedition, it is possible that the inhabitants were alive but fled and hid to avoid paying taxes. A turn from their Christian identity towards ‘the folk of America’ might have seemed expedient in these circumstances.

We should be careful with claims like this — and not only because these authors could be expressing an unsubstantiated bias. All Christendom was to some extent marked by the continuation of ‘pre-Christian’ and ‘pagan’ belief systems; the Norse realms were certainly not exceptional.

As Christianity advanced, poetry and myth became battlegrounds on which religious controversies played out. In Norway itself, poets used their medium to negotiate a dignified path between the new norm of Christianity and the deep artistic traditions associated with Norway’s ancient pantheon, especially Odin and Thor. Christianity was thus ironically ‘a stimulus to new and innovative expressions of pagan culture and identity’.13 The Icelandic sagas too were employed as tools in the power struggle between what is and what was; between Christian orthodoxy and popular mythologies like those associated with the island’s famed ‘hidden elves’, or Huldufólk.14

Greenland was a space in the universe of the sagas that, though real and familiar, was also distant, other, and mysterious. It was a canvas onto which Icelandic anxieties about religious change and continuity could be projected. Jonathan Grove has observed that the Icelandic sagas have a ‘tendency to make Greenland a theater for the religious conflicts and ambiguities remembered as having attended the transition from paganism to Christianity’.15

Hence, when the authors of the sagas told of religious strife and paganism in Greenland, they were not dispassionately reporting facts but were in all likelihood embellishing events based on a need to exteriorise tensions in their own societies. The Norse Greenlanders probably took their Christianity about as seriously as most of their brethren in other Norwegian realms, although this does not preclude a higher propensity towards materialistic conflicts with the Church over matters like taxation and property rights.

Later references to an Inuit mission

Most remaining sources that touch on the possible conversion of the Inuit in Norse times are from a much later date — after (or shortly before) missionary activity resumed in Greenland in 1721.

Many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century commentators assumed that the Inuit had been responsible in some way for the apparent evaporation of the Norse settlers sometime around 1500 CE, be that through an integration process that favoured pagan religious customs or through a violent extinction. Their emphasis was therefore on elucidating the (presumed) indisposition of the Inuit towards the (again, presumed) evangelism of the Norse.

A few of these sources are transcriptions of Inuit legends that, though containing a much older core, were most likely altered to fit the context of a Christianised Greenland. In one story told by an Inuit Christian and recorded between 1830 and 1840, it is said that the Norse were ‘good Christians, enjoying the benefits of priests and churches, and all was going well’, but that ‘they had little in common [with the Inuit] because of the difference of customs between the Christians and the pagans who had no wish to convert to the true faith’ (emphasis added).16 This story implies that attempts at conversion were indeed made, but that they were roundly rebuffed.

Some modern observers argued that an integration of the Inuit with the Norse made their modern descendants more amenable to conversion at the second time of asking.17 Their evidence was the supposed presence of many Norse loan-words in the Greenlandic language (a claim that is still debated),18 alongside a faint, latent awareness of Christian concepts that some Inuit apparently displayed.

In the book The Moravians in Greenland (1830), the success of the modern missionaries among the Inuit is attributed in part to the fact that ‘a colony of Christian Norwegians in former times settled in Greenland’, leaving in the collective memory of the Inuit ‘the glimmerings of truth … which, though debased and enfeebled, were not quite extinguished’.19

Others believed these ‘glimmerings’ were wholly lacking and therefore rejected the integration theory. In 1710, Joducus Crull of the Royal Society in London observed with regards to two Greenlanders who had been captured and taken to Copenhagen in 1605 that they surely could not have been related to the Norse, because anyone who ‘for so considerable a time been train’d up and confirm’d in the Christian Religion’ would certainly not have abandoned it, and would have immediately recognised and reprised it ‘when they saw themselves transported into a Christian Country’.20

Vestiges of an unclear past

It is impossible on the basis of these sources to develop a clear picture of the role of Christianity in the lives of the medieval Inuit, if indeed it had any role at all. Physical artefacts also provide little clarification.

One remarkable wood-carved Inuit statuette from the thirteenth or fourteenth century, found on Baffin Island, depicts a person in European-style long robes, possibly of a clerical type, with a cross engraved in the chest area. Much has been written about this statuette. Some scholars argue the cross has no particular significance, but others maintain that the statuette depicts a member of the clergy or perhaps — the most exotic speculation — a Templar.21 Even if the person depicted was from the clergy, there is no guarantee that said clergyman was engaged in a mission to the Inuit. All we can say is that the carver saw this man’s striking visage somewhere. We thus find ourselves more or less where we began, having so many more questions than answers.

Decoding the absence

A few helpful comments might be made on the sources and the medieval context. There are several possible reasons for there being so few mentions of conversion efforts among the Inuit — some quite simple, some complex; some more likely, some less — which I have grouped here into eight hypotheses:

- There were no attempts to convert the Inuit.

- All attempts failed, so there was little to report.

- The Europeans never learned enough of the Inuit language to proselytise and never found effective means by which to convey Christian concepts to the Inuit. The Inuit may also have received a thoroughly unappealing vision of what Christian life was like (e.g., the burning of one Kollgrimr on charges of practicing black magic in 1407).

- The clergy were too preoccupied with maintaining fickle Christian loyalty in the Norse settlements to justify reaching out to a whole new people.

- In the early period, the model for peasant-aristocratic church ownership (i.e., private chapels) provided a poor basis from which to spread the Gospel.

- In the later period, economic, political, and social problems — including possible excommunication — limited the Garðar bishop’s ability to act. There was no bishop in the country for long periods of time, and none at all after 1386.

- Inter-community hostility was too frequent.

- Conversely, the primary means of ‘conversion’ was intermarriage and integration with the ‘pagans’, which the authors of the primary sources (mostly clergy) may not have wished to report.

The idea that there were no attempts at all over a four- or five-hundred-year period to preach to a people whose presence in Greenland and the surrounding area was known almost from the beginning, and who were encountered in the flesh at the latest in the mid-twelfth century, seems unlikely. It would be more unusual if the Inuit truly were spared the evangelising energies of the medieval Church.

Numerous comparable examples exist of recently-Christianised medieval Europeans establishing lines of contact with ‘pagan’ peoples at the peripheries of Christendom and preaching to them the Gospel. Such spiritual expansionism was often a method for freshly-converted Christian royalties to shift the boundaries of Christendom’s imagined ‘frontiers’, bringing their own kingdoms more firmly into the Christian heartlands and diverting the attention of the Church’s proselytes onto their still-pagan neighbours. In fact, one is not even required to leave the Norwegian realms to find an instructive case study.

Sámi parallels

Historically a semi-nomadic reindeer-herding culture, the Sámi people have their ancestral home in northern Scandinavia, Finland, and the Kola peninsula. Interactions between the Germanic Scandinavians and the Sámi had been common long before the Christianisation of Norway and Sweden around the turn of the Second Millennium, but their relationship gradually intensified as the Norse and Swedes sought to exert greater economic and political control over the Far North.

While the Scandinavians underwent a top-down refurbishment of their inherited spiritual traditions, learning (or sometimes refusing) to let go of their pantheon in favour of monotheism, Sámi religion became a byword for a profane but nostalgic pagan past. As historian Alison Owen writes, ‘the Norse use[d] the Sámi as a kind of container to hold their past beliefs, which they had given up at the time of Christianisation, but still respected’.22 The Christianised authorities in Norway regarded these people as dangerous purveyors of the profane, with one early-thirteenth-century legal code warning against fraternisation with the Sámi pagans on account of their magic and divination.23

Some historians are of the opinion that the medieval Church never really tried to convert the Sámi. Owen, for example, claims that ‘there were no serious attempts to evangelise to the Sámi until the sixteenth century’.24 Alexandra Sanmark fundamentally concurs: ‘The systematic conversion of the Sami did not begin until the seventeenth century.’25 The true dawn of the Sámi’s Christianisation is often placed in 1714 when Thomas von Westen’s Lutheran Sámi Mission got underway.26

The debate effectively hinges on the meaning of the word ‘conversion’. As Siv Rasmussen explains: ‘During the medieval period, it was sufficient to participate in the Catholic minimum demands of baptism, confession and Communion to be regarded as a Christian.’ A Christian only needed to partake of the Communion once every year. In brief, medieval conversion was not the same thing as a modern pietistic ‘repentance’ in which the model convert is expected to undertake a full, emotionally explosive reorientation of their life and values. Many medieval converts continued to practice ‘pagan’ religious rites alongside their new Christian rites. The medieval Sámi were no exception. In Rasmussen’s words:

In the Christian sphere the Sámi were baptized, went to services, got married and were buried according to Christian rites. The children were given Christian names allowed by the Church. In the Sámi sphere, they practised their indigenous religion, including the use of the shaman drum and sacrifices to gods and goddesses at the sacred sites. Returning home from church after a baptism, they washed the Christian name off the child and gave it a Sámi name.27

Trude A. Fonneland and Tiina Äikäs make the same point in their edited volume on Sámi religious history: ‘Sámi religion did not only precede Christianity but was practiced simultaneously with it.’28

Probable references to Christianised Sámi people stretch back as far as Adam of Bremen’s Gesta Hammaburgensis in the 1070s, in which they are called ‘Finns’ and are described as living ‘between Norway and Sweden’. Adam of Bremen reports that these ‘are now all Christians’.29

Most Sámi people had been in contact with Christian Scandinavians or had seen church buildings by the late-medieval period, such that Christian iconography became deeply ingrained within Sámi art. Crosses, churches, and pulpits, as well as the Latin letter ‘M’ (for the Virgin Mary’) were being depicted on shaman drums and other ritual utensils.30

The impetus for evangelism in remote areas came not just from religious sources but also political sources. For the rulers of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden, the Christianisation of the Far North was fully integrated with the political goal of territorial expansion. As Lars Ivar Hansen and Bjørnar Olsen put it: ‘Christianization and church building became an important strategy in the struggles to gain political control over Sámi areas.’31

A papal letter to King Hákon Hákonarson (Haakon IV) in 1246 stipulated that Rome would recognise his rulership over the heathen ‘sambitae’ if he succeeded in Christianising them.32 Later, in 1313, Hákon Magnússon (Haakon V) decreed that the Sámi would be issued more lenient fines if they committed legal offences in the first twenty years after their conversion, likely a pragmatic measure to smooth out the difficult process of pacifying a culturally independent population unfamiliar with sedentary Christian value systems.33

In 1345, the Archbishop of Uppsala in Sweden claimed to have baptised a cohort of ‘Finns and Lapps’ (both contemporary demonyms for the Sámi). Johannes Magnus, the final Catholic Archbishop in Sweden before the arrival of the Reformation in Scandinavia, petitioned the Pope for aid in converting the Sámi,34 and a Sámi woman calling herself Margareta wrote a letter to the Danish Queen Margareta I in 1389 asking for her help to the same end.

In the year that Sweden broke away from the rule of Denmark (1523), the new Swedish King Gustav Vasa wrote to Pope Hadrian VI promising that he too would work to convert the Sámi.35 The ‘success’ of these exertions can be debated, but there can be no doubt that serious attempts were made to Christianise the Sámi before the early-modern era.

Fragments of an answer

We can draw two important points from the Sámi example: 1) The medieval Norse and Catholic authorities did believe that it was their responsibility to extirpate the paganism of people at the frontiers of their own lands and to replace it with the Gospel; and 2) For the monarchs of the North, doing so was a natural extension of their political ambitions, since converting the inhabitants of frontier lands helped them secure international recognition of their exclusive right to make laws and extract resources in those lands.

With these observations in mind, it appears that the most likely explanation for the lack of substantial references to conversion efforts among the Inuit is not that a mission of this nature was never on the cards, but rather that these efforts were sparse and largely unsuccessful, leaving the Garðar bishops with little to say on the matter. The absence of competing European powers in Greenland for most or all of this period may also have reduced the political impetus to expand, as there was no risk of another monarch converting the Inuit and by this vector gaining papal recognition of a right to rule them.

The vast cultural and linguistic differences between the two communities could have some additional explanatory power. The prolific Norse Greenland researcher Hans Christian Gulløv has argued that the Norse and Inuit could never have developed a long-lasting cultural integration because ‘the economies of the two types of societies were incompatible’, and because ‘[t]he social institutions of Norse society did not seem capable of handling encounters with the native Greenlanders’.36

However, this explanation only goes so far. Some Inuit legends recorded in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries specifically mention that ‘the Scandinavians began to learn their [the Inuit people’s] language’.37 The experiences of the missionaries in the eighteenth century also indicate that it was not impossible to establish compelling conceptual parallels between Christian ideas and traditional Inuit cosmology.38

While none of these factors is convincing in isolation, some combination of them provides the best available interpretation of the medieval Church’s extremely modest progress at the north-western edge of its world. A more definitive conclusion still eludes us.

Notes

- S. Grønlie (trans.), Íslendingabók, Kristni saga. Viking Society for Northern Research Text Series, vol. 18. (London: Viking Society for Northern Research, 2006), p. 7. ↩︎

- E. H. Jahr and I. Broch (eds.), Language contact in the Arctic: Northern pidgins and contact languages. Trends in Linguistics, Studies and Monographs, vol. 88. (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1996), p. 233. ↩︎

- ‘Eirik the Red’s Saga’. Translated by Keneva Kunz. In Ö. Thorsson (ed.), The sagas of the Icelanders: A selection (Reykjavík: Leifur Eiriksson Publishing, 1997), p. 672. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 674. ↩︎

- A. Nedkvitne, Norse Greenland: Viking peasants in the Arctic (London: Routledge, 2019), p. 341. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 91. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 137. ↩︎

- K. A. Seaver, The frozen echo: Greenland and the exploration of North America ca. A.D. 1000–1500 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996), p. 104. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 86. ↩︎

- Unknown author, ‘The Britannic islands’, in Adam of Bremen, History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen. Translated by Francis J. Tschan. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), p. 228. ↩︎

- R. W. Rix, The vanished settlers of Greenland: In search of a legend and its legacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), pp. 49–50. ↩︎

- J. Privat, Mysteries of the far north: The secret history of the Vikings in Greenland and North America (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2023), p. 260. ↩︎

- C. Abram, Myths of the pagan north: The gods of the Norsemen (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011), p. 171. ↩︎

- E. S. Bryan, Icelandic folklore and the cultural memory of religious change (York: Arc Humanities Press, 2021), p. 114. ↩︎

- J. Grove, ‘The place of Greenland in medieval Icelandic saga narrative’, Norse Greenland: Selected Papers from the Hvalsey Conference 2008, Journal of the North Atlantic, Special Vol. 2, 2009, p. 38. ↩︎

- Privat, Mysteries of the far north, pp. 84–5. ↩︎

- H. Rink, Danish Greenland: Its people and its products (London: Henry S. King & Co, 1877), p. 22. ↩︎

- H. Egede, The new perlustration of Greenland (Hanover, NH: IPI Press, 2021), p. 201; H. E. Saabye, Greenland: Being extracts from a journal kept in that country in the years 1770 to 1778 (London: Boosey and Sons, 1818), p. 61n. ↩︎

- Quoted in Rix, The vanished settlers of Greenland, pp. 195–6. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 94. ↩︎

- Seaver, The frozen echo, pp. 39–40; Privat, Mysteries of the far north, pp. 98–9. ↩︎

- A. Owen, ‘Sámi, land and faith in Viking age Scandinavia’, Epoch Magazine, 1 September 2023. https://www.epoch-magazine.com/post/non-attempts-at-converting-the-s%C3%A1mi ↩︎

- A. Sanmark, The Christianization of Scandinavia — a comparative study, PhD thesis, University College London, 2002, p. 170. ↩︎

- Owen, ‘Sámi, land and faith’.

↩︎ - Sanmark, The Christianization of Scandinavia, p. 139. ↩︎

- S. Rasmussen, ‘The protracted Sámi Reformation — or the protracted Christianizing process’, in L. I. Hansen et al (eds.), The protracted Reformation in northern Norway: Introductory studies (Stamsund: Orkana akademisk, 2014), p. 78. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 79. ↩︎

- T. A. Fonneland and T. Äikäs, ‘Introduction: The making of Sámi religion in contemporary society’, in T. A. Fonneland and T. Äikä (eds.), Sámi religion: Religious identities, practices and dynamics (Basel: MDPI, 2020), p. 3. ↩︎

- Adam of Bremen, History of the Archbishops, pp. 205–6. ↩︎

- L. I. Hansen and B. Olsen, Hunters in transition: An outline of early Sámi history (Leiden: Brill, 2013), pp. 224, 317–18. ↩︎

- Fonneland and ÄikäsIbid, ‘The making of Sámi religion’, p. 141. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 158. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 315–16. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 316–17. ↩︎

- Rasmussen, ‘The protracted Sámi Reformation’, p. 83. ↩︎

- H. C. Hans Christian Gulløv, ‘The nature of contact between native Greenlanders and Norse’, Journal of the North Atlantic, vol. 1, no. 1, 2008, p. 22. https://doi.org/10.3721/070425 ↩︎

- Privat, Mysteries of the far north, p. 58. ↩︎

- D. Crantz, The history of Greenland, including an account of the mission carried on by the United Brethren in that country, vol. 2 (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1820), p. 20. ↩︎