Christ the King Church in Nuuk, Greenland. https://www.katolsk.gl/.

- Laying the foundations

- Building a church

- Reaching the faithful, inviting the masses

- A settled church life

- New shoots

- Notes

In Catholic discourses outside Greenland and Denmark, the most common emotional mode when discussing the history of Catholicism in Greenlandic society is ‘wistfulness’; a bittersweet reminiscence of what was and what might still have been; a resigned acknowledgement that Protestantism has functionally won the denominational battle in this vast territory. In one 2019 article by Jonathan Wright in the Catholic Herald, readers are reminded that ‘Greenland was once a Catholic bastion’ during the era of Norse settlement (roughly 1000–1500AD). While Wright acknowledges that the Catholic Church ‘happily’ made a minor comeback in its once-secure North Atlantic redoubt in the mid-twentieth century, it hardly attained to its past pre-eminence: ‘Greenland has a population just shy of 60,000: this includes only 50 or so Catholics.’1

One-hundred-and-ten years earlier, in the first volume of the 1909 Catholic Encyclopedia, Joseph Fischer also emphasised the role of Catholicism in the discovery of North America by way of Greenland, and in a literary flourish he lamented the fate of the Catholic Greenlanders when the Church’s contacts with the island were severed, the inhabitants being ‘deprived of religious ministration’ and the remaining faithful possessing ‘as a memorial of Catholic times only the corporal on which a hundred years before the Lord’s Body had been consecrated by the last priest’.2 Another entry by Pius Wittman in the sixth volume of the Encyclopedia relegated the Catholic era in Greenland to the distant, long-dead past: ‘The church history of Greenland naturally divides itself into two periods: the Catholic period, from about 1000 to 1450, and the Protestant period, since 1721.’3

Missionaries in this ‘Protestant period’ acknowledged — approvingly — that Catholicism was frozen out of Greenlandic Christendom. Despite occasional spats between the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Denmark and the Moravian Brethren in Greenland in the eighteenth century, the Moravian David Crantz celebrated that both shared ‘the same fundamental faith’, including ‘the doctrine of justification before God by free grace’, i.e., not Catholicism.4

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Catholic opinions concerning the state of Christianity in Greenland under the stewardship of the Protestant missions were unsurprisingly negative. In The Northern Light: A Tale of Iceland and Greenland in the Eleventh Century (1860), an anonymous novel, the author praised the return of Christianity to Greenland but regretted that the Greenlanders were deprived of the ‘consistency and effect which Catholicity can only give’.5 Some even blamed the Reformation for the loss of contact between Norse Greenland and Europe, lamenting that in the wake of Christianity’s great schism it was inevitable that ‘silence and oblivion [should] fall on Greenland’.6

Despite the mist of dejection hanging over it, Catholicism in Greenland has undergone a quiet revival since the early-to-mid-twentieth century.

Laying the foundations

Some members of the Lutheran establishment in Godthåb/Nuuk, the country’s capital city, feared a Catholic revival in Greenland before it had even begun. In 1929, the Lutheran priest Knud Balle wrote with some concern: ‘Roman Catholicism, with its beautiful service, the weight attached to the observance of certain external commandments and the idea of deserving acts, would in many respects appeal to the Greenlanders at their present stage of development’.7 According to Flemming A. J. Nielsen, head of the Department of Theology at the University of Greenland, ‘the Catholics had missionary activities [in Greenland] from the 1930s’,8 but the rejuvenation truly got under way in the 1950s.

This was made possible by the ‘opening’ of Greenland that started in the 1940s. Greenland experienced unprecedented exposure to the ‘great wide world’ during the Second World War, and Greenlanders, despite the efforts of the Danish authorities to limit their interactions with outsiders, suddenly had opportunities to meet some of the thousands of US service-people travelling to and from the newly established Thule Air Base in the north.9 In 1941, Eske Brun, the Danish governor of Greenland during the war, met a Catholic field chaplain as part of a US detachment scoping out conditions on the island, and during a trip to the areas of Norse settlement Brun pointed the chaplain to the location of ‘the ruins of the oldest Catholic church in the western hemisphere’, which ‘made a deep impression on him’.10

Though Greenlanders could not yet attend a Catholic service themselves, they were aware through their news media that Catholic services were being held on their island at Thule Air Base.11 The base was made permanent in the early 1950s, ensuring further cultural encounters in the decades to come.12

Another vital change came in 1953, when Greenland’s colonial status was abolished in the new Danish Constitution. Suddenly, the Lutheran Church of Denmark no longer had a legal right to exclude other religious organisations in Greenland, prompting fears of ‘division and disunity’ and turning churches into ‘theological battlegrounds’.13

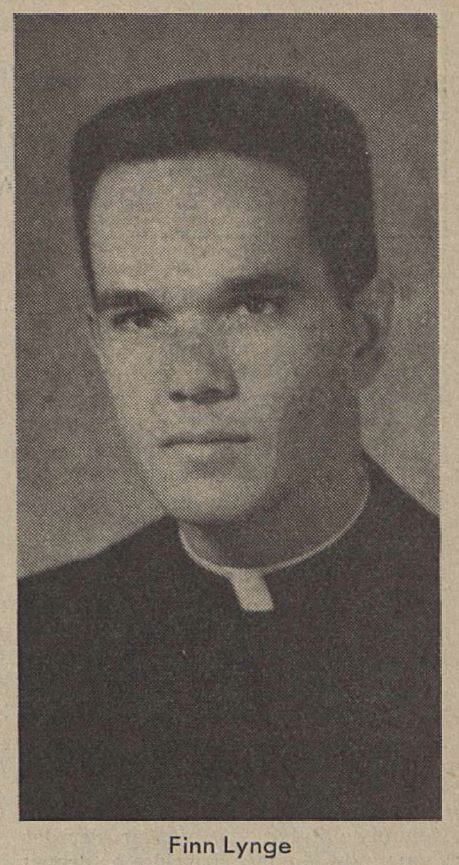

The late 1950s saw the arrival of many new religious organisations in Greenland, of which the Catholic Church and the Jehovah’s Witnesses arguably sparked the greatest interest in the press. Following a radio report, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, the leading newspaper in the country, announced in January 1958 that ‘a young Greenlander’, an Inuit man named Finn Lynge, was undergoing training and would soon ‘come to represent the Catholic Church in Greenland’. The Lutheran establishment in Godthåb/Nuuk quickly attempted to control the narrative, delivering descriptions of the doctrinal differences between Lutheran and Catholic theology that the staff at Atuagagdliutit perceived to be ‘one-sided and negative’.14

Subsequent discussions in the newspaper show that the looming threat of Catholic competition caused a degree of panic among Lutheran loyalists. One article discussed the need for the ‘People’s Church’ to revitalise itself so as not to find itself pushed in an undignified manner into ‘preventive measures against sects or, for example, against a hard-working Catholic mission’.15 Other articles noted an urgent need to beautify Greenland’s ‘sad and unsightly’ Lutheran churches to make them more appealing than prospective new Catholic buildings, which, after all, were known for their beautiful ornamentation. This specific concern kicked off a localised golden age in Lutheran church decoration.16

Building a church

American Catholic priest Michael Wolfe, originally destined for a field chaplain role at the Thule base, arrived in Greenland in the spring of 1960 and established himself in a repurposed US Jamesway hut (a portable hut designed for use in harsh weather environments, including in polar and sub-polar regions) in a poor neighbourhood of Nuuk.17 He was briefly joined by another priest, Tim Killeen, the following year.18 In 1962, Catholic authorities in Copenhagen promised that their intention was not to initiate a religious takeover of the island, but Lutheran leaders remained cautious, insisting that Greenland’s traditional Protestant institution was a core organ of the ‘popular community’ of the nation — ‘a community that we do not want to see broken up’.19

A radio discussion was hosted on 13 February 1962 between representatives of the Lutheran Church and the new religious movements establishing themselves in Greenland, including the Catholic Church. The conversation succeeded in lowering the temperature somewhat by focusing on shared Christian values and a common desire to contribute to the economic and cultural modernisation of Greenland. As Atuagagdliutit reported: ‘The Catholic priest Ib Andersen suggested [during the discussion] that a Catholic mission could help us to think in new ways.’ However, the author of the article was not wholly convinced, accusing the Catholic Church of harbouring a ‘tyrannical take on Christ’ and a ‘deeply unchristian, ecclesiastical arrogance’.20 Lutheran loyalists described the Catholic Church’s activity in the early 1960s as a ‘charm offensive’ that sought to ingratiate the Church into Greenlandic society while maintaining the (presumably insincere) pretence that it was not a ‘mission’.21

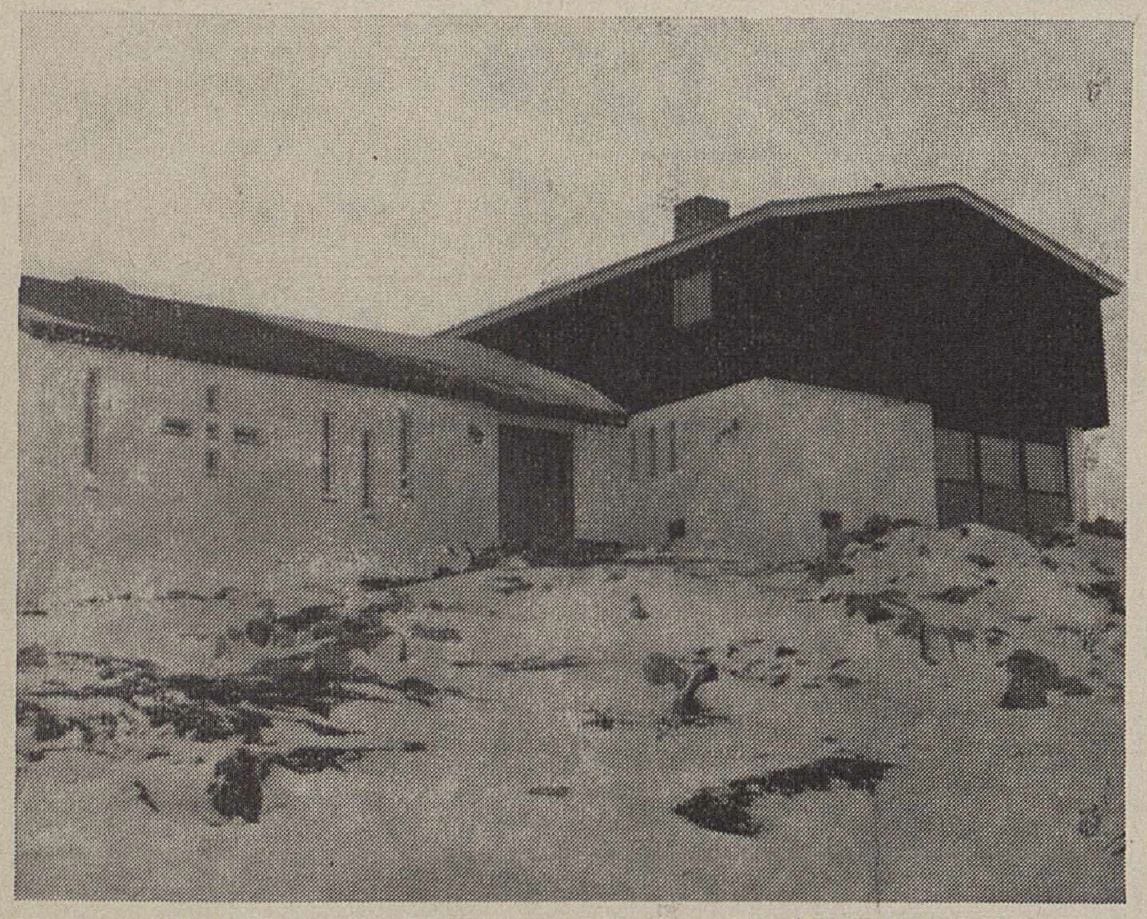

Hypothetical discussions gave way later in 1962 to a more grounded discussion around the construction of a Catholic base, Krist Konges Kapel or Christ the King Chapel — and an attached residence affectionately called ‘the monastery’ — in Godthåb/Nuuk. Wolfe oversaw this work, the targeted completion date being 1 March 1963, after which he said the priority would be to enable the Greenlanders ‘to get to know the Catholic Church’. He noted that ‘several Greenlanders’ had already approached him to ask questions about Catholicism.22

In the meantime, Wolfe engaged in soft rhetorical warfare with the Lutheran establishment. On 14 March 1963, he wrote in Atuagagdliutit that he worried about Catholic Greenlanders being ‘relegated to a quite passive and more or less oppressed position’ due to an atmosphere of intolerance towards any challengers to Lutheranism.23 Lutheran priest Svend Erik Rasmussen bit back by painting the Catholic Church’s leadership structure as an authoritarian hierarchy quite at odds with the values of Lutheranism and, therefore, Greenlanders.24

Later that month, Atuagagdliutit published an interview with Finn Lynge, who at the age of 30 became ‘the first Catholic priest with Eskimo blood in years’. Lynge told of his conversion to Catholicism during his education in Denmark in 1952, after which he spent time in France, Rome, and the United States and became a member of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. The plan was now for him to finish his preparations at his order’s pastoral seminary at Pass Christian in Mississippi, and then travel to Greenland in 1965 to take up a priestly role.25 He arrived in Godthåb/Nuuk, as planned, in September 1965, taking the reins from the recently-retired Michael Wolfe who had decamped to Copenhagen.26

Reaching the faithful, inviting the masses

With its homegrown priest in place and its chapel built, the Catholic Church in Greenland finally began the work of teaching the Greenlanders about this new-yet-ancient way of practising Christianity. A newspaper advertisement on 3 March 1966 promoted a session at the chapel titled ‘What is the Catholic Church’, at which the basics of Catholicism would be laid out. Interested parties could then participate in Catholic Orientation — 20 lessons for a price of 25 Danish kroner.27 In a 1966 article in the Tidsskriftet Grønland, a long-running journal dedicated to Greenland studies, Lynge explained that the challenge of serving the scattered Greenlandic Catholics ‘has been — and still is — a demanding task; the distances in this world’s largest parish mean that the time and money spent on a parish tour do not bear any reasonable relation to the ecclesiastical service the Catholics get out of it’.28

As for the relationship between the Catholic Church and non-Catholic Greenlanders, Lynge related that the goal was not to convert Lutherans into Catholics but rather ‘to make [the Catholic Church’s] life and teachings accessible to the Greenlandic population’.29 At the same time, he was very determined to extol the virtues of ecclesiastical diversity, proclaiming: ‘The time of the ecclesiastically homogeneous nations will soon be over.’30

In subsequent interviews, Lynge reassured sceptical Greenlanders that his Church did not regard them as ‘heretics’, saying that people should ‘believe what they want’ but that it was ‘healthy for society’ to have a plurality of options. He repeated the official position of the Catholic Church: ‘We do not consider Greenland a mission field.’ Rather, the purpose was to serve the ‘existing Catholic congregation’ in Greenland, which numbered around 50 in February 1967.31

The Church purchased a small aeroplane — a Piper Super Cub worth 90,000 Danish kroner32— to facilitate its work in the more remote settlements, and though the plane crashed in January, Lynge still hoped to visit all settlements with Catholic residents at least twice per year. Other aims were to contribute to the education of the Greenlanders and to publish religious literature in Greenlandic. Despite Lynge’s studiously collaborative and conciliatory tone, some doctrinal battles were still breaking out between his congregation and the Lutherans over such controversial subjects as Catholic ‘indulgences’ — works or ordinances that reduce the weight of sin that any given believer might have.33

Other contributors to Atuagagdliutit were warming up to the idea of an ‘ecclesiastical common market’ in which the toleration of differences between Greenlanders could make Greenland as a whole a stronger community.34 Lynge himself attained a high degree of acceptance from other Greenlanders. On 1 July 1974, after a unanimous vote by the board of the company, he became head of Greenland Radio’s operations,35 completing a rapid transformation in which Catholicism had gone from being a suspicious outsider that threatened Greenland’s Lutheran national unity to being an embedded subcommunity in Greenlandic society whose star representative held a position of great cultural influence.

When Lynge retired from the clergy in order to marry in 1975,36 he did so as a statesman of sorts, and that is not even counting his extensive career as a campaigner for Indigenous rights or his service as a diplomat, Member of the European Parliament, politician for the Siumut Party, and government official.37 Lynge died in 2014 aged 80.38

A settled church life

By the late-1970s, the intermittent rhetorical battles in Atuagagdliutit over the apparent dangers posed by this exceptionally mild-mannered Catholic revival had faded away. The way was now clear for the congregation to enjoy a more settled, less contentious existence.

An overview of Catholic Greenland’s history in the final decades of the twentieth century and into the first years of the twenty-first is provided by a November 2007 profile of the Nuuk congregation and its priest, Father Paul Marx, published on the Catholic Whispers website.39 According to this source, three sisters from the Little Sisters of Jesus, a Catholic women’s community, established a ‘fraternity in Nuuk’ in 1980. After 1997, the congregation did not have a permanently resident priest, but was served instead by a commuting priest from Copenhagen. In this capacity, Fr Paul Marx was spending around seven or eight months per year in the country.

Sunday attendance usually ranged from 6 to 23, with the congregation as a whole comprising 50 people, of which 46 were ‘non-Greenlanders’ and 30 did not live in Nuuk. Interestingly, a 1995 report in the National Catholic Reporter also put the number of Catholics in Greenland at 50.40 There were fifty Catholics in 1967, fifty in 1995, and fifty in 2007 — a consistency that accords well with Finn Lynge’s insistence, quoted earlier, that the Church’s purpose was to serve an existing congregation rather than to turn Greenland into a ‘mission field’.

The Greenland Church momentarily attracted international attention in September 2007 when the Religion, Science and Environment institute hosted an interfaith conference on climate change in Narsarsuaq on the southern tip of the island (in the same area where there once stood a Benedictine nunnery in the fourteenth century). The US Cardinal Theodore McCarrick urged an ecumenical effort to preserve God’s natural creation.41

New shoots

In early 2009, responsibility for the congregation was transferred to the Institute of the Incarnate Word / Instituto del Verbo Encarnado (IVE). This has opened up new cultural connections with Catholic communities in South America and has prompted a number of Spanish-speaking Catholics to visit Nuuk.42

Climate change has begun to indirectly influence the course of Catholic history in Greenland. Receding ice-caps have opened new opportunities for mineral resource extraction, a booming industry in a country desperately seeking independent revenue streams.43 As discussed in another profile of the Greenland congregation published in the Danish Christian magazine Kristendom.dk in 2016, the need for additional labour has contributed to a rising number of immigrants to Greenland from places as far afield as the Philippines and Poland, causing the congregation to double in size from 50 in 2007 to 100 in 2016.44

Many of these new congregants do not speak fluent Danish, so English-language services are now held alongside Danish services and the website of Christ the King Church in Nuuk (katolsk.gl) presents its information in both Danish and English. For the first time since the original Christianisation of Greenland in the early eleventh century, the Roman Church is undergoing genuine numerical growth in this vast territory. Contrary to the 1909 Catholic Encyclopedia, it is apparent that the ‘Catholic period’ of Greenland’s history is not wholly finished.

As per the Kristendom.dk report, the Little Sisters of Jesus still had a presence in Nuuk as of March 2016. One of the two sisters was serving in Queen Ingrid’s Hospital, the largest medical institution in the country, as she had done for ‘many years’. By April, though, the Little Sisters order had decided to pull out of Greenland. The mayor of the Kommuneqarfik Sermersooq municipality met with the nuns, Agnes Deprez and Noële Simon, to say farewell and thank them for their decades of voluntary work, particularly with abused women.45

Today, Christ the King Church remains a part of the Nuuk cityscape and continues to serve its increasingly diverse and geographically dispersed flock. Being a Catholic in Greenland no longer causes raised eyebrows.

Notes

- J. Wright, ‘Greenland was once a Catholic bastion — then the Church vanished’, Catholic Herald, 5 September 2019. https://catholicherald.co.uk/greenland-was-once-a-catholic-bastion-then-the-church-vanished/ For similar, see: G. Ryan, ‘Leif Erikson: The first person to reach North America was a Catholic Viking’, uCatholic, 11 October 2019. https://ucatholic.com/blog/leif-erikson-the-first-person-to-reach-north-america-was-a-catholic-viking/ ↩︎

- J. Fischer, ‘Pre-Columbian discovery of America’, in C. G. Herbermann et al (eds.), The Catholic Encyclopedia: An international work of reference on the constitution, doctrine, discipline, and history of the Catholic Church, Volume 1 (New York: The Encyclopedia Press, 1913), p. 422. ↩︎

- P. Wittman, ‘Greenland’, in C. G. Herbermann et al (eds.), The Catholic encyclopedia: An international work of reference on the constitution, doctrine, discipline, and history of the Catholic Church, Volume 6 (New York: The Encyclopedia Press, 1913), p. 778. ↩︎

- D. Crantz, The history of Greenland, including an account of the mission carried on by the United Brethren in that country, vol. 2 (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1820), p. 123. ↩︎

- R. W. Rix, The vanished settlers of Greenland: In search of a legend and its legacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), p. 202. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 54. ↩︎

- K. Balle, ‘The Church of Greenland of the present day’, in M. Vahl et al (eds.), Greenland, volume III: The colonization of Greenland and its history until 1929 (London: Humphrey Milford/Oxford University Press, 1929), p. 255. ↩︎

- F. A. J. Nielsen, ‘Religion and religious communities’, Trap Greenland. https://trap.gl/en/kultur/religion-og-trossamfund ↩︎

- E. Beukel, ‘Greenland and Denmark before 1945’, in E. Beukel, F. P. Jensen, and J. E. Rytter (eds.), Phasing out the colonial status of Greenland, 1945–54 (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2010), pp. 29–32. ↩︎

- E. Brun, ‘Grønland i Adskillelsens Aar’, Grønlandsposten, vol. 4, no. 18, 1 December 1945, p. 266. https://timarit.is/page/130972 ↩︎

- ‘THULE — et stykke Amerika i Grønland’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 93, no. 21, 8 November 1953, pp. 394–5. https://timarit.is/page/3777348 ↩︎

- K. H. Nielsen, ‘Transforming Greenland: Imperial formations in the Cold War’, New Global Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2013, pp. 130, 134. https://doi.org/10.1515/ngs-2013-013 ↩︎

- K. Kjærgaard, ‘Mellem sekulariseret modernisme og bibelsk fromhed: Fromhedsbilleder og moderne kirkekunst i Grønland 1945–2008’, Fortid og Nutid: Tidsskrift for kulturhistorie og lokalhistorie, June 2009, no. 2, pp. 108, 113. https://tidsskrift.dk/fortidognutid/article/view/75443 ↩︎

- ‘Læserbreve og klip’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 98, no. 2, 30 January 1958, p. 9. https://timarit.is/page/3779657 ↩︎

- ‘Folkekirkens ansvar’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 98, no. 8, 24 April 1958, p. 3. https://timarit.is/page/3779801 ↩︎

- ‘Grønlandske kirker er triste og uskønne’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 98, no. 21, 9 October 1958, p. 9. https://timarit.is/page/3780117 ; ‘Den katolske aktion’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 100, no. 8, 20 May 1960, p. 28. https://timarit.is/page/3781309 ↩︎

- Kjærgaard, ‘Mellem sekulariseret modernisme og bibelsk fromhed’, p. 110. ↩︎

- F. Lynge, ‘Den katolske Kirke i Grønland: Status og målstæning’, Tidsskriftet Grønland, 1966, no. 2, pp. 40–1. http://www.tidsskriftetgronland.dk/archive/1966-2-Artikel02.pdf ↩︎

- ‘Om at jage på Folkekirkens græsgange’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 2, 18 January 1962, p. 19. https://timarit.is/page/3782714 ↩︎

- ‘Et folkekirkeligt monopol gik tabt’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 2, 1 March 1962, p. 19. https://timarit.is/page/3782799 ↩︎

- ‘Konfirmation’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 103, no. 10, 9 May 1963, p. 19. https://timarit.is/page/3783731 ; ‘Om medarbejderskab’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 104, no. 4, 13 February 1964, p. 15. https://timarit.is/page/3784345 ↩︎

- ‘Katolsk kirkebygning står færdig i Godthåb til marts’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 102, no. 22, 22 October 1962, p. 13. https://timarit.is/page/3783299 ↩︎

- ‘Et ganske pudsigt sammentræf?’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 103, no. 6, 14 March 1963, p. 10. https://timarit.is/page/3783602 ↩︎

- ‘I anledning af et læserbrev’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 103, no. 6, 14 March 1963, p. 10. https://timarit.is/page/3783610 ↩︎

- ‘Grønlænder bliver første katolske præst med eskimoisk blod i årerne’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 103, no. 7, 28 March 1963, p. 11. https://timarit.is/page/3783631 ↩︎

- ‘Hjem til Grønland’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 105, no. 19, 16 September 1965, p. 10. https://timarit.is/page/3785696 ↩︎

- ‘Katolsk Orientering’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 106, no. 5, 3 March 1966, p. 18. https://timarit.is/page/3786108 ↩︎

- Lynge, ‘Den katolske Kirke i Grønland’, p. 41. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 47. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 48. ↩︎

- ‘Grønland er ingen missionsmark’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 107, no. 4, 16 February 1967, pp. 4–5. https://timarit.is/page/3786911 ↩︎

- Lynge, ‘Den katolske Kirke i Grønland’, p. 42. ↩︎

- ‘Betydningen at ordet aflad’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 108, no. 2, 18 January 1968, p. 18. https://timarit.is/page/3787702 ; ‘Svar på Kirsten og Ole Dams læserbrev’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 108, no. 5, 29 February 1968, p. 10. https://timarit.is/page/3787786 ↩︎

- ‘Kirkeligt fællesmarked’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 111, no. 4, 18 February 1971, p. 21. https://timarit.is/page/3790418 ↩︎

- ‘Finn Lynge biver måske radiofonichef’, Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, vol. 114, no. 21, 30 May 1974, p. 2. https://timarit.is/page/3793381 ↩︎

- C. Grymer, ‘Den katolske grønlænder’, Kristeligt Dagblad, 11 October 2010. https://www.kristeligt-dagblad.dk/boganmeldelse/den-katolske-gr%C3%B8nl%C3%A6nder ↩︎

- ‘Finn Lynge 75 år’, Sermitsiaq, 22 April 2008. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/finn-lynge-75-ar/153688 ↩︎

- N. Molgaard, ‘Finn Lynge er død’, Sermitsiaq, 4 April 2014. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/samfund/finn-lynge-er-dod/687479 ↩︎

- Greenland priest’s unique Catholic parish’, Clerical Whispers, 30 November 2007. https://clericalwhispers.blogspot.com/2007/11/greenland-priests-unique-catholic.html ↩︎

- P. Lefevere, ‘A Catholic in Denmark is one of the lonely few’, National Catholic Reporter, 31 March 1995. https://web.archive.org/web/20100831043459/http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1141/is_n22_v31/ai_16783208/ (archived from the original). ↩︎

- ‘Cardinal McCarrick urges rescuing planet’, Zenit, 9 December 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20120927020624/http://www.zenit.org/article-20485?l=english (archived from the original). ↩︎

- P. F. Schilereff, ‘“The heart of the mission” (IVE in Greenland)’, Chronicles IVE, 2 May 2013. https://www.instituteoftheincarnateword.org/the-heart-of-the-mission-ive-in-greenland/ ↩︎

- F. Sejerson, ‘Brokers of hope: Extractive industries and the dynamics of future-making in post-colonial Greenland’, Polar Record, vol. 56, no. e22, 2020, pp. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247419000457 ↩︎

- K. Nielsen, ‘Sammenhold og risiko for snestorm styrer Grønlands katolske menighed’, Kristendom.dk, 30 March 2016. https://www.kristendom.dk/synspunkt/katolsk-menighed-gr%C3%B8nland ↩︎

- ‘Nonnerne forlader Grønland’, Sermitsiaq, 1 April 2016. https://www.sermitsiaq.ag/kultur/nonnerne-forlader-gronland/129186 ↩︎

3 responses to “Greenland’s quiet Catholic revival”

[…] point for many religious groups seeking to enter Greenland, including Jehovah’s Witnesses and Catholics. But for the Bahá’ís, who had already made some progress through the remote distribution of […]

LikeLike

[…] in the Restorationist strand of Christian theology that combines aspects of Protestant doctrine and Catholic ecclesiastical tradition. It has had a small presence in Greenland since 1989. At its height, the […]

LikeLike

[…] into Greenland when the Lutheran ecclesiastical monopoly was abolished in 1953 – including Catholics, Adventists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Bahá’ís – the Pentecostal movement was one of the few […]

LikeLike